Are 16-year-olds better off taking Algebra II or getting a part-time job?

Reading a study that everybody cites as saying the opposite of what it says.

I just came across an interesting study that is also meta-interesting in the way people choose to cite it. Here are some samples:

[Algebra II] has a positive impact on higher education and career outcomes (Gaertner, Kim, DesJardins, & McClarty, 2014). (source)

Numerous studies have documented the benefits of enrolling in additional years of high school mathematics including greater odds of persisting in and graduating from college (Adelman, 1999; Byun, Irvin, & Bell, 2015; Gaertner, Kim, DesJardins, & McClarty, 2014), higher earnings (Rose & Betts, 2004), and a greater likelihood of majoring in STEM fields (Wang, 2013). (source)

Students who complete algebra II are also more likely to have higher college GPAs, graduate from college, and have higher earnings in later life (Gaertner, Kim, DesJardins, & McClarty, 2014). (source)

Texas stopped requiring Algebra II for high school graduates in 2014. However, researchers in math education advise parents to strongly encourage their students to take Algebra II (Gaertner, et al.; Ketterlin-Getter, 2014). (source)

There is little to no association between taking Algebra II and job attainment, advancement, or salary (Gaertner, Kim, DesJardins, & McClarty, 2013). (source)

That last one differs a bit from the others. It’s citing the same work, just using the online publication date in 2013 instead of the print publication date in 2014. And yet it summarizes the study as having pretty much the opposite conclusion. What’s going on with that?

Well, for one, that last citation is from a book written by Gaertner and McClarty. So the main difference is that the other citations were from people who didn’t author the paper being cited. And also maybe never read it.

What Does It Actually Say?

I came to this study because I got curious after reading a debate between Kelsey Piper and Matt Barnum on whether colleges should be teaching more, or less, remedial math. More and more college students need remedial math lessons, because primary and secondary schools kind of stopped teaching actual math. Should colleges respond to that trend by tightening their standards or by embracing their new de facto role as junior high math teachers?

I don’t have an answer, but one step towards figuring it out, it seems to me, should be to first estimate how impactful remedial math is. Is your life better if you know how to round a large number to the nearest hundred? How much better? Do some demographics benefit more than others?

There are plenty of studies on this, but very few that actually try to figure out causality. Kids who get good grades in math become, on average, more successful adults—but surely a good chunk of that is because grades are correlated with intelligence, diligence, how rich your parents are, and what colleges you get into. How much of that advantage comes from people benefiting from knowing more math, either because they get into a lucrative STEM career or they use it in other careers and everyday life?

So this took me, eventually, to Preparing Students for College and Careers: The Causal Role of Algebra II (Gaertner, Kim, DesJardins, & McClarty, 2013). They used a clever study design to try to sidestep a lot of those confounding variables. High school students choose how much of their time and energy to invest in school. They might decide to spend that time and energy on a part-time job instead. For this reason, high unemployment rates in a school district are correlated with students taking more advanced math classes. If you can’t get a job, might as well study math instead.

All of that is of course horribly confounded with economic background and school quality, so they don’t use it directly. Instead, they use it to determine how much the opportunity to get a job trades off against taking Algebra II in your sophomore year, and then use a more randomized natural experiment—how old are you in your sophomore year? In many areas, at 15 years old you’re subject to child labor laws that sharply limit your hours, while a 16-year-old can legally work much more. Depending on your birthday, you might be unemployed for some of your sophomore year due to being a few months shy of 16 years old. At which point, again, why not spend that time learning math?

So, they argue, we can measure the causal impact of taking Algebra II in sophomore year by looking only at the students whose birthdays indirectly determined whether they took it. They used two large datasets for this: the high school sophomore class of 1990 from the National Education Longitudinal Study of 1988 and the sophomore class of 2002 from the Education Longitudinal Study of 2002, both of which were U.S. Department of Education projects. These studies followed students through college and several years after, looking at how things like grades and curricula in high school correlated with things like college success, then after-college income and happiness.

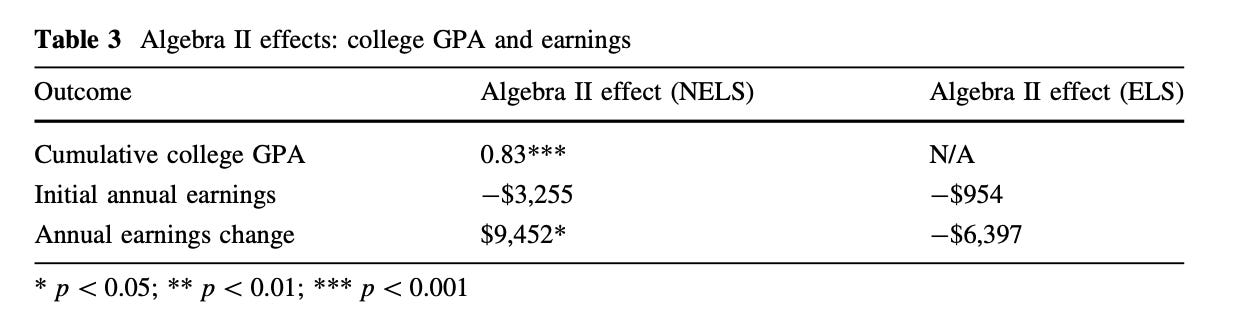

What they found was mixed. Taking Algebra II in 1990 definitely improved your college outcomes—you were more likely to graduate and your college GPA improved by 0.83 points, which is a shockingly large number in this context (GPA is a 4-point scale). For the class of 2002, they didn’t have access to college GPA data yet, but their retention data pointed in the same direction.

Algebra II improved your performance in college. But it didn’t improve the rest of your life. The 1990 dataset showed a small positive effect on metrics like income and “occupational prestige,” but the 2002 dataset had a similarly-sized negative effect. Taking Algebra II instead of getting a part-time job meant making $7000 dollars less each year once you eventually entered the workforce full time. Not all of these were statistically significant, though, including the negative effect on the more recent cohort.

This is a fascinating result, but it uses a complicated methodology that could easily have subtle flaws, so I starting searching for commentary on the paper. What I found was people citing it as though it had gotten the opposite result. And then I Became Enraged, which doesn’t tend to motivate my best writing but sure does motivate me to write.

What Went Wrong Here?

The basic problem, at both the object-level and the meta-level, is that people’s brains tend to collapse certain distinctions. Once you’ve assumed that things are correlated, you don’t feel a need to distinguish them so much. Success is success, right? Better grades, better college, better job, better life. Presumably learning is involved in there somewhere.

So the authors of those citations, I imagine, looked at this paper. They saw that it measured both college outcomes and life outcomes, and found significant effects of Algebra II on college outcomes. And then they felt like they were done. They ignored, elided, or flat-out did not read the part on life outcomes, because college outcomes and life outcomes feel like they should be the same thing.

Moreover, they were rarely “reading” it out of curiosity. They were all just looking for a citation for “algebra is good” so that they could get on with their argument for how best to teach it. You can see that pretty clearly in my second example, where the author seems to have carefully placed the citation so that she’s not technically lying about the contents, suggesting that she was aware of its conclusions and chose to ignore them. This one was a doctoral dissertation in education, so she might reasonably have expected more scrutiny and therefore been more rigorous. Still, at the end of the day, she was researching in advocacy mode, not learning mode.

And, in broad strokes, I think this cognitive bias is why math education has been allowed to get so useless that you’d be better off spending that time behind the cash register at a convenience store. When we’re comfortable equating college and life outcomes, then the value of Algebra II becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, a way students can signal their worth to colleges. It no longer has to do anything else.

So, at the meta level, my takeaway is that any article about the value or importance of education should be expected to include, ideally prominently, discussion of its intrinsic value. We need to stop talking about college like it’s the goal. College is a means, not an end. Education needs to center learning, not gatekeeping.

At the object level…I still don’t feel like I know very much after all this. But one tentative thought is that college admissions should start explicitly treating high-school age work experience as equivalent to spending the same amount of time in a classroom. I’m sure they often do roughly that, informally, as a way of not being as biased against poorer applicants. But if they do it consistently, and openly, I bet more of their students will come in knowing how to round a number to the nearest hundred. If numeracy is a basic real-world skill, let the real world teach it.

You know every time you write about math I want to learn math. Or relearn it. Not arithmetic, which seems more and more unnecessary (except for rounding up or down, I guess), but algebra, even calculus, though I have ptsd from that. I wonder--here's the question--how much does your homeschooling experience influence your opinion. Which prepared you more for your life--studying math or working at the book store?