Let's Go To Greece

There's a modern medical breakthrough hiding in ancient myth.

I found Erik Hoel’s latest, We Are Not Low Creatures, exciting and inspiring. We should go to Mars, and learn the secrets of life we now know are hidden there.

In that vein, I have my own proposal—we should finally do a study of a lake in Kastria Cave in Greece to learn why drinking from it cures alcoholism.

Ever Ready To Restore Humanity

I’m stealing this idea from Osborne Aldis, who is part of an odd dynasty of radical Quakers that definitely deserves its own article. Three generations, at least, of antiquarian public health doctors and part-time con artists. Watch this space.

Osborne Aldis went to medical school, like his father and grandfather before him, but ended up working as a Doctor of Fine Arts. In a 1914 letter to The Saturday Review, a London newspaper, Aldis crosses the streams. He starts with a discussion of alcoholism as a public health issue and suggests some political remedies. But at the end, seeming a bit sheepish, he adds one more suggestion. He quotes the following lines from Ovid’s Metamorphoses (written circa 8 CE):

Clytorian streams the love of wine expel,

Such is the virtue of the abstemious well.

We know where the ancient city of Clytor was, he points out. Shouldn’t somebody fund an expedition to investigate this story?

The point for consideration is whether in the analysis may be found one of those hidden secrets of nature, so long neglected, but ever ready to restore fallen humanity to the more ennobled ideal of manhood. We need not refer to the well-known properties of many waters, which most probably would have been long since lost sight of and forgotten had it not been for the confirmation of modern science.

Unsurprisingly, I don’t think anybody ever did this. They’d probably find nothing and look stupid. You need a richer, more populous civilization before you have resources to spare to chase down every legendary magical spring. It’s too bad, though, because there’s strong evidence that Aldis was completely correct.

The Cave of the Lakes

Any unusual property of the waters of Clytor would need to come from an unusual feature of the surrounding watershed. Since I’m much better at Googling things than people in 1914 were, I can tell you what the One Weird Thing about the area is: the Cave of the Lakes, which would’ve been maybe 5 miles from the ancient city and was rediscovered in 1964. This beautiful tourist attraction, also known as Kastria Cave, has 13 separate lakes inside it…sometimes. During the winter, melting snow joins the lakes into a single river and carries the water out. People, usually young women, have spent some time in the cave since the Stone Age, so it has been studied in modern times, but by archaeologists, not doctors.

When ancient Greek sources get more specific than “Clytor,” they tend to describe the magical waters as coming from this cave, or one matching its description. Drinking from its water could remove the craving for wine, among other psychological ailments. You couldn’t wash things with it, though, the legends say.

Water you can’t wash with is generally “hard water,” water with a heavy concentration of certain kinds of minerals. Soap doesn’t lather in hard water. You also, typically, shouldn’t drink too much of it. It’s a nice cave to visit, but you wouldn’t want to live there. It makes some sense that the unusual structure of the cave and its water could lead to unusually hard water, even by cave standards.

But what, specifically, is in the water in Kastria Cave? Absent a chemical analysis, we can still make at least one inference from pictures of it:

It has light-colored stalactites. Lots of them. Stalactites, from the Greek for “drips,” are almost always formed by dripping water depositing little bits of dissolved calcium carbonate, which over millennia accumulates into a big fossilized drip. There’s probably other minerals involved, too, but calcium is almost certainly the main thing in the water.

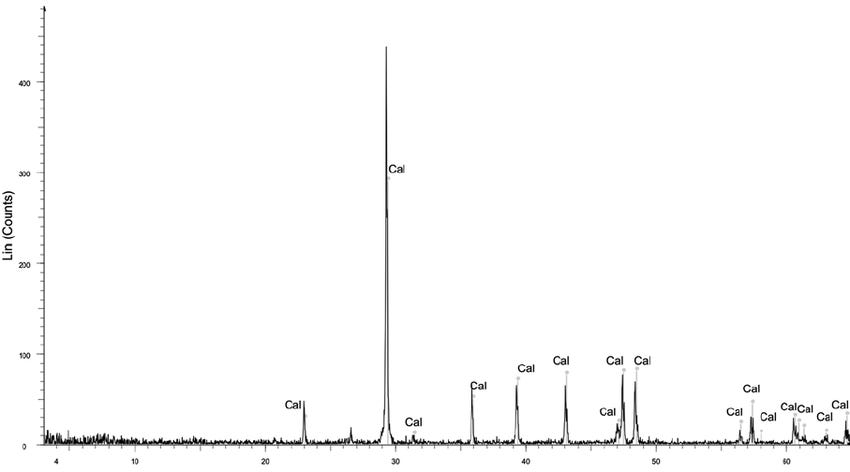

This guess is also supported by a 2013 study on the diverging evolution of cyanobacteria in different Greek caves. The researchers did an x-ray diffraction analysis of the cave walls, and in the case of Kastria it came out “oops, all calcium.”

So, what, are we saying calcium cures alcoholism?

Yes.

We thought, for a while, that that the drug acamprosate, brand name Campral, was one of the best ways to treat alcohol withdrawal symptoms and reduce cravings. It was developed by pharma giant Merck, and demonstrated in multiple clinical trials to be highly effective. It’s been prescribed since 1989. Acamprosate’s proprietary ingredient is a synthetic molecule, C5H11NO4S, and to turn it into a pill it’s combined with calcium, which dissolves quickly once swallowed, leaving the big fancy chemical to do its work. That’s the idea, anyway.

But in 2014, researchers at the University of Heidelberg reported that if you take the calcium out, if you use something else to make the “pill” part of the pill, the drug stops working. If you take the medicine out but keep the calcium, the drug seems like it works just as well. The calcium was the active ingredient the whole time, hiding in plain sight. While research is still ongoing to confirm these results, every experiment done so far has pointed in the same direction. (But it’s not definite, and there’s a lot of individual variation, so if your doctor is prescribing acamprosate you should stick to it.)

Calcium carbonate isn’t magic. As usually defined today, it isn’t even technically a cure. It treats withdrawal. You still need to decide to quit, and to stick to it. But for many people, it makes a significant difference to both comfort and probability of relapse. So while I can’t prove it (yet), I think it’s very probable that the cave of ancient myth that cures alcoholism has actual power, and that studying it could still be helpful today, to check and refine our understanding.

Modern medicine is very empirical. We’ve known that acamprosate works, but not why it works, since the eighties. If we end up confirming the recent findings, all that means is that we’ve gone from not knowing why acamprosate works to not knowing why calcium works. This is progress, and it’s also a sign that there are scientific discoveries waiting to be made. Knowing why would tell us where to look, how to improve further, whether that’s through inventing more synthetic chemicals or testing more natural ones.

So why have we taken so long to look into it?

For once, I’m not going to blame the 20th century for this oversight. Quite a few traditional or legendary treatments have been investigated and found to be completely bogus. As Tim Minchin sings, “I don’t believe just ‘cause ideas are tenacious, it means that they’re worthy.” The hypothetical society that found this, the one that read Ovid and mounted an expedition into the Greek highlands to search for a lost cave, would have wasted energy on a hundred similar quests that went nowhere. We’re likely better off, on net, that they didn’t.

But we here in the 21st century don’t have the same excuse. We’re rich enough to fund a hundred times as many projects as we could in 1914. We’re past the point where it makes sense, at a civilization level, to investigate these long-shots. We could, as Hoel puts it, Just Do Things. But we mostly don’t. I think most of the things holding us back are the habits of poverty. Our level of risk-tolerance, the strictness of our gatekeeping, is calibrated for scarcity that no longer exists. Among other institutional problems, the current U.S. administration, in trying to move us forward via widespread science funding cuts, has it exactly backwards. As does the standard way to naysay going to Mars— “Not until we’ve solved all the problems here on Earth.” We should be bolder, and try to have it all.

Plus, if I can get self-serving and meta here for a second, we could try to make more space for polymaths. (See also Paul Bloom’s recent article). People like Osborne Aldis, who could make the connection between the withdrawal symptom delirium tremens and the madness described in Ovid’s poetry, were already being marginalized by his time, while nobody batted an eye at his father or grandfather straddling the same disciplines. Here, too, I don’t really blame the 20th century. They were richer than the 19th, and therefore could afford more specialization. But with the advent of the modern internet, it’s generalism that has gotten cheaper. I didn’t need specialized knowledge to find or interpret the existing studies of Kastria Cave, nor the clinical trials of acamprosate and calcium. Rather, I needed a specific skillset—the ability to do some quick-and-dirty research and make the connections. And for society as a whole to discover this, it just needed to indulge enough weirdos like me that eventually one of us would randomly read a letter in a scanned century-old periodical.

We are not low creatures. We are the scions of Melampus, the hero of myth who found the cave, who could cure even the madness visited upon himself by a vengeful divinity. We will find our way—to sanity, to sobriety, to peace, to Greece, to Mars.

I had to click your links to be sure you weren’t pulling a Sam Kriss on us! This is an amazing story, and your suggestion about a lack of polymaths is on point, honestly.

Paul Bloom was my undergraduate honors thesis advisor at University of Arizona in 1998-9. I did a study on theory of mind.