More On Crime

Cancer remains much worse.

An old-ish article of mine has recently gotten more attention (thanks, Philosophy bear!). Here’s the original:

My quick summary: “Cities are higher-crime than rural areas, but also richer and safer. People there live longer lives, suffer fewer injuries, and probably experience less trauma and are more likely to get help when they do. This shows that crime levels aren’t that important to the health of a community—they’re more than canceled out by other effects of population density.”

People have shared some criticism, some of which I think is valid and some of which I want to rebut.

(content warning: programmatic data visualizations of like every bad thing that can happen to someone)

Criticisms That Are Correct

Leukemia vs. Crime

My post asserts, without much evidence, that the second-order/indirect effects of leukemia and crime are probably about the same. I chose leukemia as a stand-in for “generic bad thing that does the same amount of first-order harm” and it may not have been the best example. Leukemia is the most common cancer in children, but it’s still mostly an old person’s disease, meaning its victims are losing fewer years of life, on average, than murder victims. I’ll get into some figures below that suggest that, to take age into account, I should’ve said something like “20% of all cancer cases,” because cancer takes five times as many “disability-adjusted life years” as crime does in developed countries.

But that tweak doesn’t get at the crux of this objection, which is the theory or intuition that lives or life-years lost to cancer have smaller indirect effects than those lost to crime. To some extent, this objection misses the point. Something other than crime clearly has larger second-order effects, given the rest of the stats. If a city has more than twice as much violent crime as rural parts of its state, but city people live longer and have more money, something good is happening to outweigh the bad. Part of which is better quality of medical care, part of which is other benefits of urban density.

For example, take…well, maybe New York City is too incendiary a topic right now. Let’s look at, I don’t know, Minneapolis instead. Minneapolis’s rate of violent crime is more than triple the rate of the rest of the country. That is bad! That is first-order bad and has bad second-order effects. But Minneapolis also has a 15% lower age-adjusted death rate and 15% higher median household income than Not Minneapolis, USA. By any standard measure other than crime rates, they’re doing much better. Maybe we should look into some sort of federal intervention in Not Minneapolis, because it clearly has more severe problems.

Marginal Value of New Investment

Another idea my article floats, and then doesn’t particularly support with direct evidence, is that a dollar spent on cancer research will probably do more good than a dollar spent on crime prevention. This is hard to prove or disprove—we don’t know how good the runners-up for research grants were, or how the recent surge in possible-cancer-treatments is going to translate into patient outcomes.

I think the best argument for this idea is to demonstrate that the marginal dollar spent on crime prevention does very little, which makes it easy for cancer research to win. That’ll be its own section.

Relatedly, Elias Beamish 「 The Void 」makes the very good point that all of my crime and cancer statistics come from a universe where we spend much more on crime prevention than on cancer research, which makes crime look like a smaller relative problem than it actually is. It’s like if we’d just spent a trillion dollars successfully deflecting a giant asteroid heading for Earth, and then I wrote an article about how giant asteroids have caused zero deaths so why are we spending so much money on deflecting them?

Here, too, the best defense is to argue that most of our crime prevention dollars are not preventing crime, as I will below.

Murder

In the bonus section on murder rates, I’m dismissive of the idea that murders have only declined relative to aggravated assault because of improvements in modern medicine. Homicides really have declined more than other violent crime, it’s just only apparent over long time scales because they were always a tiny share. So just gesturing at the correlation between aggravated assault and murder isn’t really enough. Commenters at Astral Codex Ten looked into this, and it’s complicated. I’ll link and summarize their thoughts in a separate section.

But it’s in the bonus section because it’s not really relevant to the main thesis. Even if we weirdly stipulate that the shift in ratio means crime is just as bad as if there were five times as many murders, that still just upgrades it from leukemia to lung cancer.

Criticisms That Are Wrong

“Actually, we can quantify how much damage crime and cancer are doing by converting everything into dollar values, and see that crime is doing more.”

The fallacy here is that those quantifications include the money we’re spending. If spending $250 billion on crime automatically makes it a $250 billion-dollar problem, we’ve lost our ability to judge anything we’re doing.

“Cancer victims are mostly older than crime victims, so going by a per-capita rate is misleading.”

This is true, but many of the statistics in the original article are “age-adjusted,” meaning they already take that into account. Cancer kills more children than homicide does. It doesn’t become less bad by also killing their parents and grandparents.

“Crime lowers property values and cancer doesn’t.”

I covered this one in the original, but people are still saying it so I’ll expand a little here. It’s true that people and businesses are less interested in moving to places with higher crime rates. People also don’t like to move to high-cancer-incidence areas, but this doesn’t come up as much in everyday life. I guess I should point out that property values in Chernobyl are zero, but I don’t know how convincing that is. The point is maybe more that you can see what crime is doing to a neighborhood, so surely it’s worse?

Outliers aside, the damage done by cancer to communities is harder to see because it’s evenly distributed. We can’t meaningfully compare a high-cancer and low-cancer neighborhood. But that doesn’t mean it’s less important—something happening Everywhere All At Once is, in fact, an argument that it’s more important. Cancer in children and young adults has made each recent generation 1-3% smaller, among other things, so it’s robbed us of the labor and innovation of people who never existed, or who died too young.

Also, again, cancer’s just an example. In aggregate, we can see that crime isn’t doing all that much to property values by noting that the same price that buys you a mansion in the country will, in the city, buy you a parking space on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

(De-)fund the police

Okay, time to get into the pretty central question of anti-crime spending, which is does it do anything?

Results here are mixed. It’s surprisingly easy to find studies that argue that changes in police funding don’t have any effect on crime rates (1, 2). But more recent studies, and also common sense, argue that if you hire more cops, you deter crimes. Mello (2018) looks at which counties got increased federal hiring grants to help police departments recover from the Great Recession, and what happened to the crime rates there. He calculates that, at least when the economy’s bad, a city that got a free 3.2% increase in police funding reduced the overall cost of crime by about 3.5%. He concludes that “On net, the evidence suggests that the program is cost-effective, but it is difficult to say for sure.”

So the marginal dollar invested in anti-crime spending probably does reduce crime a jot, but it’s a smaller effect size and harder to measure than I’d naively expected.

Let’s compare, once again, cancer. Cancer death rates have fallen 32% since 1991. While changes in crime rates are mostly driven by economics, and only fractionally attributable to anti-crime spending, we can attribute all of that 32% fall to anti-cancer spending, in one form or another. It’s not that cancer decided to go easy on us. In fact, as countries get richer and healthier, their cancer death rates should by rights increase, since more people live long enough to get a deadly cancer. So the 32% figure is actually understating the achievement.

Here’s one way to sort of quantify the difference we’ve been able to make so far in each area. Crime spending is a recurrent cost, while each individual cancer study is a one-time cost. So it seems vaguely fair to compare the effects of changes in crime spending with the effects of total spending in cancer research. Since 2009, law enforcement spending has risen about $100 billion. We’ve also spent about $100 billion total on cancer research. In return, we’ve seen a 0-3.5% drop in crime attributable to that spending (going again by Mello and assuming his data is representative), and a 32% drop in cancer deaths. This is all pretty sketchy and speculative, but taken at face value it suggests that cancer was ten times as “elastic” over that period.

Counterargument: But what if we had effective law enforcement?

When I’ve raised this point in arguments online, the “crime is more important” side generally concedes that modestly increasing or decreasing police funding has at best a modest effect. “But,” they go on, “we know how to do this better. If we use policies that have been empirically proven to work, mostly in other countries, we’d massively decrease crime.”

Sadly, by “policies that have been empirically proven to work,” they don’t tend to mean “make everybody richer.” They tend to mean giving the state a broad latitude to detain, imprison, and execute people it deems likely to do something violent. They point, in particular, to El Salvador, which has successfully made it safe for 98% of its people to walk alone at night by imprisoning the other 2% of them.

Ethics aside, I would argue that we have way too much empirical data about what happens when you give the state broad authority to imprison people without transparency, oversight, or restraint. You get an authoritarian regime, which is not conducive to human flourishing. It’s not even conducive to safety, in the medium term. It took about two seconds for El Salvador to expand the scope of its crackdown from “suspected gang members” to “people who say the crackdown is bad,” and by now they’ve moved on to “women who can’t prove they haven’t had an abortion.” And El Salvador is the best success story anyone can point to.

It’s also a bit of a fallacy to judge something by its best possible implementation, rather than the kind of implementation we actually get. We in the U.S. voted for a “tough-on-crime” government in 2024. Their best idea seems to have been “well, maybe some of the people who were going to commit crimes also have unrelated immigration violations?”

Contrast this with the effectiveness of the “make everybody richer” approach in practice. Liberal economic models, warts and all, have massively lowered crime. Over the past 30 years, we’ve seen most kinds of crime fall more than 50%, sometimes 90%, in liberal countries. Some of them were tough on crime, some soft, it didn’t really matter. When there’s a correlated trend across all democracies, it’s not because of crime policy.

Litigating the Example

There’s limited value in debating questions like “which is worse, crime or (some subset of) cancer?” It’s not generally possible to move a dollar from one to the other overnight. But they do trade off in terms of the attention individual people, and legislatures, pay to them. So I’ll get into some different ways of comparing them.

First of all, this is not necessarily something we can come to a consensus on, because of values differences. There are a lot of people who just consider “how safe people feel walking the streets at night” to be inherently very important, and that’s valid. As a society, we owe it to those people, at minimum, to ensure that there are always places for them to live happily. But safe-feeling streets don’t have to be society’s top priority. We don’t need to spend all of our attention cracking down on crime, construction sites with bad scaffolding, people sneezing in public, and overly-realistic Halloween costumes.

That said, we do have a few standard ways of comparing different kinds of harm. The most convenient to look up is Disability-Adjusted Life Years, or DALYs. A DALY is a year of life lost either because you died a year sooner or your quality of life decreased. Different disabilities are weighted differently—Alzheimer’s cuts your quality of life by two thirds, while losing a finger cuts it by 10%.

Subjective and complicated as they are, DALYs are useful because they distinguish between tragedies in a way that feels roughly right to most people. A child dying is more tragic than an adult dying. Going blind at age 25 isn’t the same as dying, but you’ll “lose a few years” adjusting.

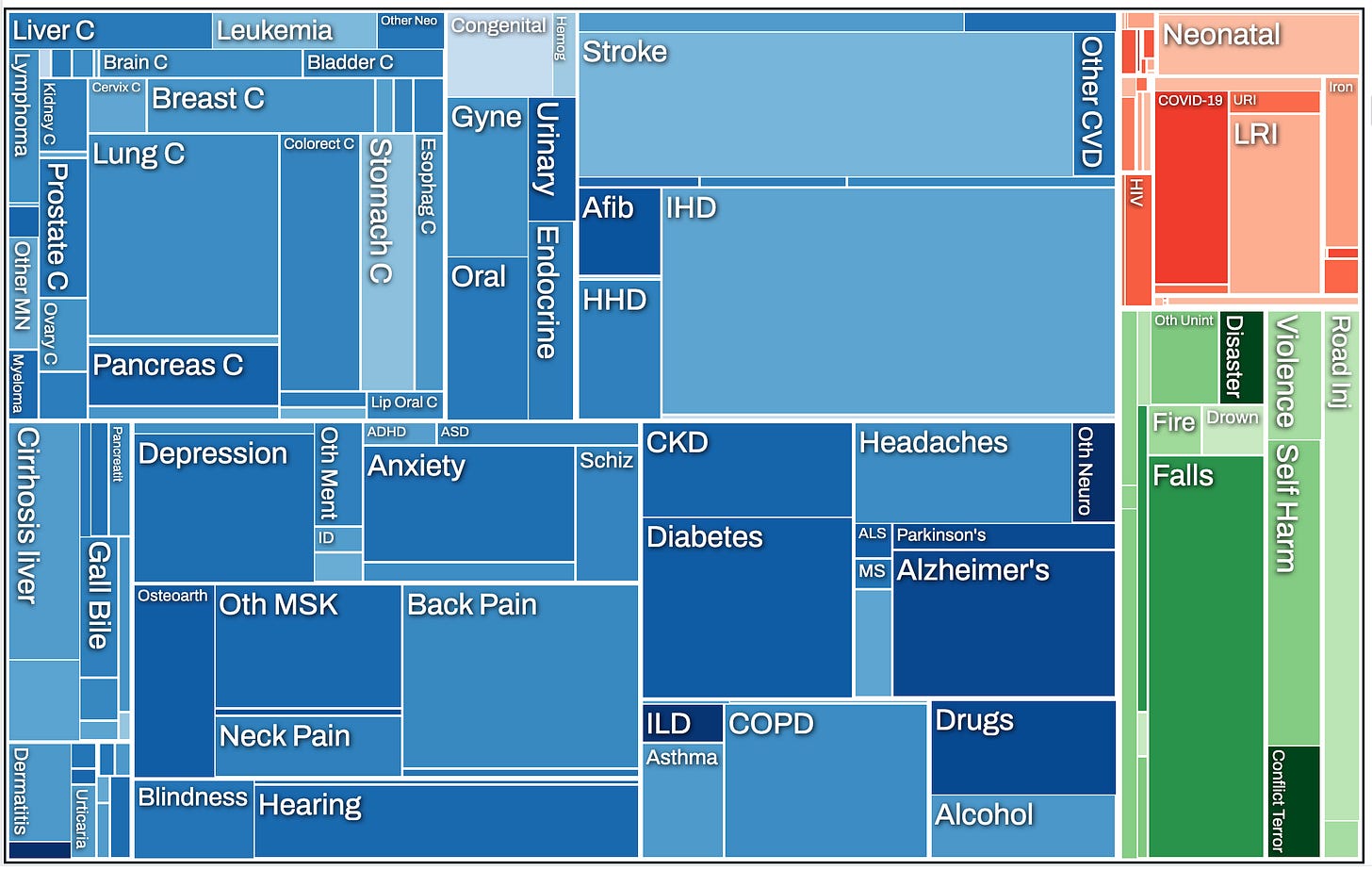

According to the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, here’s where our lost DALYs are coming from in developed countries:

The bigger the box, the more DALYs lost. (That giant IHD box stands for Ischemic Heart Disease). Leukemia and violence are both on there, and you can see that they’re in the same tier. In this dataset, leukemia is costing 0.53% of our DALYs and violence is costing 0.71%.

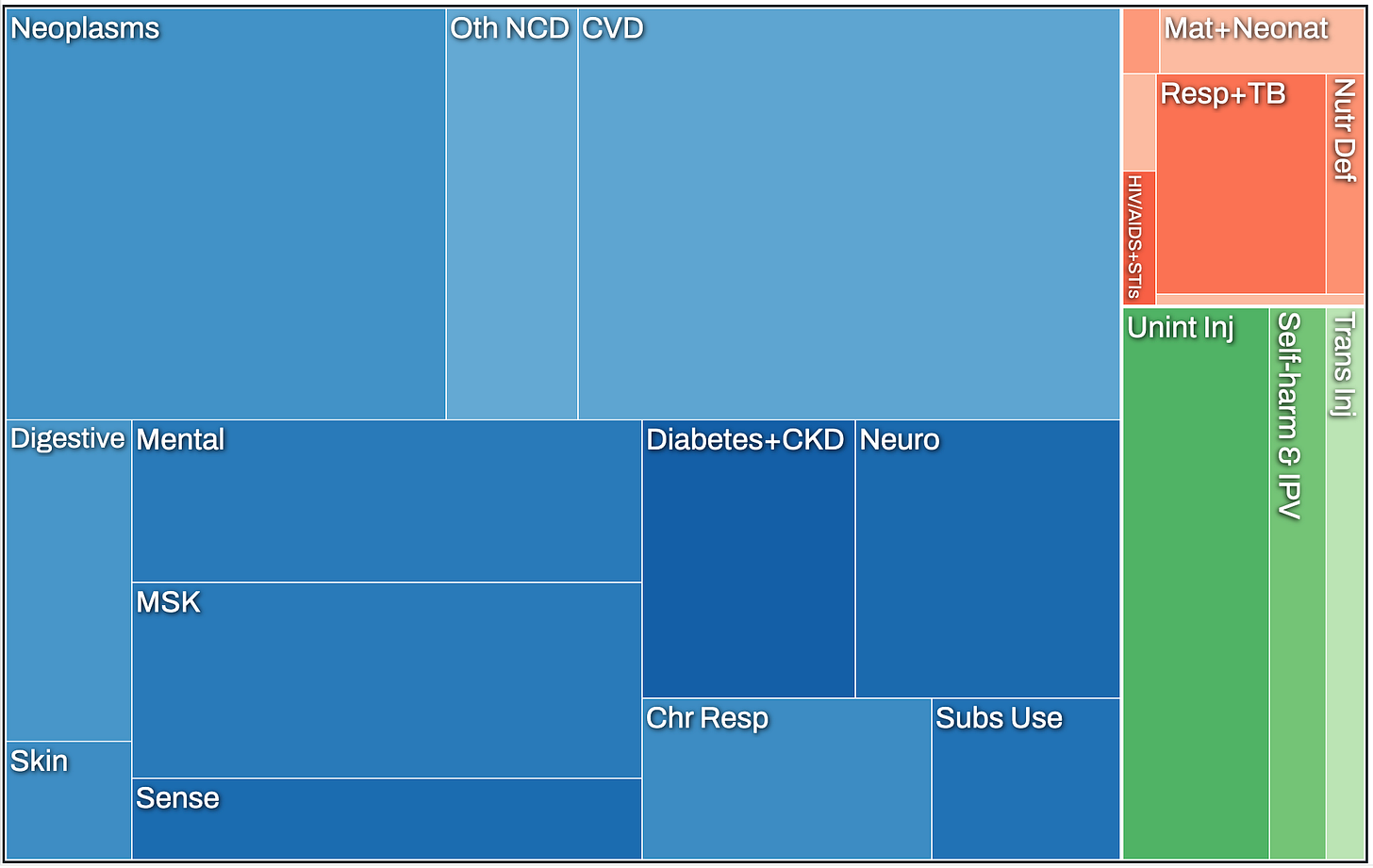

If we zoom out a bit, collapsing all cancers into “neoplasms” and all self-harm and interpersonal violence into one box of their own, the difference is stark.

Cancer, by this method, steals 15.66% of all DALYs, while violence steals 2.77%.

This method misses a few things. It doesn’t take into account that we spend much more money on crime prevention (broadly defined) than cancer prevention (narrowly defined). That’s relevant if you’re considering the counterfactual where we completely ignored both, but not all that relevant to a marginal cost calculation.

It also doesn’t take into account dread. This is often where these conversations go—people argue that high crime rates create a pervasive feeling of insecurity with all sorts of subtle effects. I’m sure there’s something to that, but I want to emphasize that those effects are so subtle that, at a high granularity, they don’t show up in any other ways of measuring well-being, or not strongly enough to overcome the advantages of population density. According to the Gallup World Poll in 2020, people in more urban areas (which always have higher crime rates than rural ones) report more happiness, less food insecurity, and higher incomes.

I’m also not sure it’s true that we dread crime more than cancer. There have been studies! According to the 2025 Chapman Survey of American Fears, our two top fears are “corrupt government officials” (for some reason) followed by illness. 59% of Americans report being “afraid” or “very afraid” of someone they love becoming seriously ill, while only 27.5% report the same about “walking alone at night.” If you ask it more concretely, fear of being murdered or sexually assaulted by a stranger clocks in a little higher at around 32%.

Our dread of crime manifests more physically because there’s more we can do about it—move away, don’t walk alone at night, hire cops, put up streetlights. But it’s not necessarily stronger in aggregate. (And I continue to assert that “there’s not a lot you can do to save yourself” is not a point in favor of cancer.)

In Summary

We don’t have a great way to spend more money directly on crime prevention. We do have a great way to prevent crime, though. We prevent it by helping people thrive. Let’s focus on how to do that better.

Okay, Let’s Get To The Murder

How much of the fall in murder rate is attributable to improvements in medical care? People in the ACX comments made some good qualitative points on both sides. ugh why, whose username is also my brain’s reaction to being told it has to do more murdercancer research, shares this incredibly apt quote from David Simon’s Homicide (the non-fiction book, not the TV adaptation):

The [homicide detective] unit's institutional memory includes a few 300-plus [murder] years in the early 1970s, but the rate declined abruptly when the state's shock-trauma medical system came online and the emergency rooms at Hopkins and University started saving some of the bleeders.

On the other hand, the equally aptly-usernamed cowboykiller points out that if the goal of all the murder skepticism is to prove that crime, in some sense, “hasn’t actually gone down,” this flies in the face of casual observation.

…you'd never hear about people going to much of Oakland and neighborhoods like Third Ward, Houston that didn't live there when I was growing up and now they seem mostly fine? And despite living in a kind of crappy part of Houston, not exactly a low crime city, for many years I know don't know a single person who has even gotten so much as held up for their wallet? N=1 of course, but claims about omnipresent danger in American society are so common online it makes me wonder if I'm not just weirdly lucky.

Others looked for N>1 statistics. Jonathan Lafrenaye did the most heavy lifting:

EMS only responded to ~70% of homicide victims in 2022. (https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/74/ss/ss7405a1.htm)

2007 review of patients of gunshot and stabbing victims being brought to Philly level 1 and 2 trauma centers found 16% were DOA and another 11% died of their wounds at the hospital. (https://penntoday.upenn.edu/news/survival-rates-similar-gunshot-stabbing-victims-whether-brought-hospital-police-or-ems-penn-med)

Another study showed gunshot wound mortality going from 16% to 10% among admitted patients over the course of 20 years (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28697020).

Back of the envelope math: 30% do not get an emergency response. 41% get a response but die before reaching the hospital (70% x 16/27). 29% get a response and die at the hospital (70% x 11/27).

Dropping mortality from 16% to 10% on admitted patients only reduces deaths for the 29% that arrive alive. That would be an 11% overall reduction in murders from improved care.

Take away: I put my estimate on murder reduction due to increased trauma care at 20%, with a range of 10-25%. My data was from different places at different times but is consistent with other articles that I read over in my admittedly quick review.

This calculation makes one assumption that is reasonable but apparently wrong: that the rate at which victims survive the trip to the hospital is roughly constant. Sam Harsimony found a study (from Baltimore, the same city Homicide is talking about) showing that, between 2007 and 2014,

…the rate of deaths from gunshots and stabbings stayed about the same. But when they looked more closely at where patients died, they discovered a striking trend: The rate of pre-hospital death rose significantly, while the rate of in-hospital death decreased. Specifically, the odds of a gunshot victim dying before reaching a trauma center increased fourfold, while the odds of a stabbing victim dying increased by eight.

Some of that might be due to guns getting more lethal. Also, maybe with improvements in trauma care, emergency responders have started making an effort to get patients in worse shape to the hospital. But I doubt either of those apply much to stabbings. If a stab victim becomes 8 times less likely to reach a hospital alive, it’s because they’re getting stabbed more thoroughly. That supports my original guess that murderers try to compensate for improved care.

The most likely answer is that everyone here is basically right—over some time periods, we can attribute as much as 25% of the decline in murders to improved medical care, but that effect diminishes over time as murderers (and murder weapons) adapt. The rest of the decline in murders can still be attributed to technological and social progress, same as the decline in aggravated assault.

And by “social progress,” I’m including here some social progress within the world of organized crime. It stands to reason that mobsters will have been working diligently to reduce the incentives for other mobsters to murder them, recapitulating the same evolution that’s happened in broader society. They’ve probably traveled a bit down the same road by which Vikings transmuted themselves into Norwegians.