The Princess and the Porcupine

The royalist and the royal behind the 1830s democratization of Britain.

In 1830, King George IV died, completing a hardcore self-destruction that had been the work of twenty years. In his decade as regent and decade as king, he had neglected his duties in favor of extravagant parties. Overeating, over-drinking, and probably an opioid addiction all contributed to his death. His public immorality and staunch opposition to any and all reform had led to widespread and escalating riots. Major newspapers openly celebrated his demise.

That November, the new king William IV reconvened Parliament and made the traditional speech. In it, he condemned the recent Belgian Revolution and the burgeoning revolt at home. “I am determined,” he said, “to exert to the utmost of my power all the means which the Law and the Constitution have placed at my disposal, for the punishment of sedition, and for the prompt suppression of outrage and disorder.” As is also tradition, Parliament then immediately debated how to respond to the speech.

A radical Whig and former party leader, Charles, the Earl of Grey, was among the speakers. Grey was 66 years old and had been in Parliament since he was 22. For almost all of that time, the Whigs had been out of power. Even when they theoretically won elections, George IV had used his royal prerogative to keep the Tories in. Grey’s faction had formed fleeting coalition governments twice under his father: the first had conceded American independence, while the second abolished the slave trade. George was not interested in round three.

In his speech that day, Grey pointed out what was missing from the king’s. William had not even acknowledged the grievances being protested, much less suggested that they might, in any way, be addressed. The rioters were being framed as the pawns of outside agitators, when in fact they had legitimate concerns.

I cannot pass from this part of the subject without expressing my full conviction, that Parliament will direct its best efforts to remedy the evils which have led to this species of disturbance, and though the people of that country have been driven to commit excesses, I trust that their spirit is yet sound, that they have English hearts in their bosoms, and that when they become satisfied that the Legislature is anxiously engaged in devising means for their relief, they will be restored to a sense of what they owe to themselves, and to society.

If we in government do our duty, he argued, the people will do theirs. The Belgian Revolution shows what will happen if we don’t.

Next and last to speak was the Prime Minister. Arthur, Duke of Wellington, had defeated Napoleon once and for all at Waterloo. He had leveraged that glory to become a powerful conservative leader. Two years ago, he’d become the Prime Minister. George IV had given him only one instruction on forming his government: he could appoint anybody he liked, except Charles Grey. Grey’s faction had won seats in the election triggered by George’s death, and Grey’s speech today had gotten a worrisome amount of applause. Wellington knew his duty.

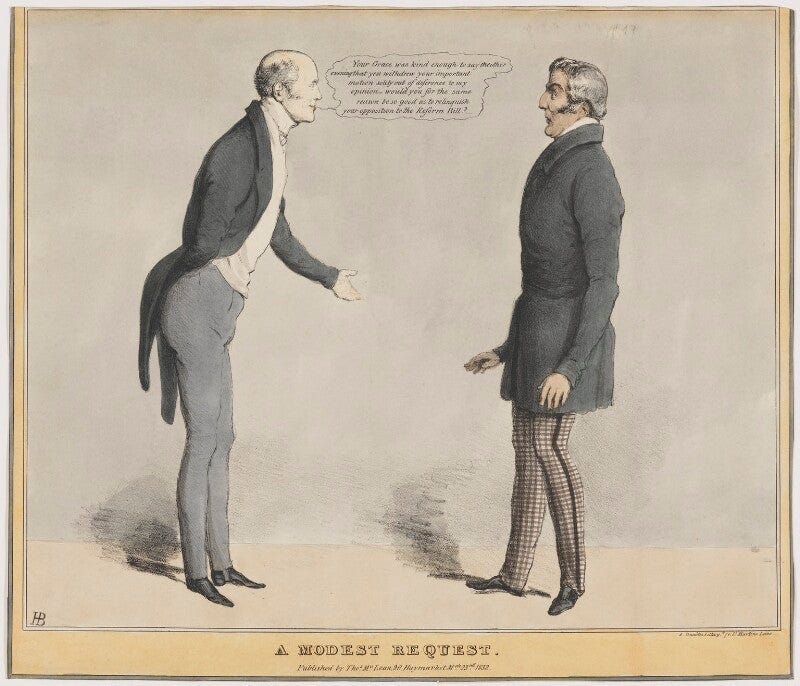

In his customary terse and direct style, Wellington rebutted Grey point by point. Wellington could not imagine any possible improvement to the current laws, he said. He concluded by promising that he would never bring forward any reform measures, and that, in the words of the Parliamentary reporter, “as long as he held any station in the government of the country, he should always feel it his duty to resist such measures when proposed by others.”

Two weeks later, he no longer held any such station. Charles, Earl Grey, was the new Prime Minister.

Why Grey Won

The popular revolt leading to this momentous shift started decades earlier with the radicalization of one of the country’s least radical people. William Cobbett, the third son of a farmer, had joined the army and risen through the ranks…as far as you could go without buying a commission, which wasn’t very far. Cobbett was an idealist and unbendingly principled. During his service in Nova Scotia, 1785-1791, he discovered and documented evidence of corruption among some of the commissioned officers. On returning and being discharged, he presented the evidence to the authorities and was ignored. So he published a book calling out the many injustices he’d witnessed in the army.

Cobbett may have been naive, but he wasn’t stupid. He quickly got a strong sense that he should get out of England, right now, having made many powerful enemies and zero powerful friends. He first tried moving to France, but with the revolution there in full swing, he didn’t really feel any safer. So he fled to Philadelphia.

His plan, he said, was just to teach English to French immigrants, using the limited French he’d picked up. But in his classes, his students would read aloud from American newspapers, and Cobbett was outraged at what they were saying. America seemed to be falling under the spell of the very worst people in England: Joseph Priestley, William Godwin, and Mary Wollstonecraft. He was compelled to turn to political writing, trying to help Americans see sense.

In his 1795 A Bone to Gnaw for the Democrats, he condemned the British government’s failure to censor the three.

It would have been a very easy thing for the Government, if they had exerted that vigilance which, on such an occasion, it is their indispensible duty to exert…

But His Majesty's ATTORNEY GENERAL, though a very worthy man, and a very good Lawyer, is unfit for the station which he occupies. I will not indeed admit the supposition that his intimacy with Mr. Grey and some other leaders of the Opposition can have the smallest effect on his public conduct…but there is certainly something reprehensible in such intimacies…

As you can imagine, this stance did not win him friends in America. But he doubled down, writing a monthly tract called The Censor, and then tripled down with a daily newspaper, Porcupine’s Gazette. Neither, for some mysterious reason, were a success. Nor was his royalist bookstore with the picture of King George in the window.

In the middle of this doomed stand, he was approached by a French spy, who wanted to bribe him to switch sides. Cobbett may have been epically bad at reading the room, but trying to bribe him was an even more ludicrous misreading. The spy was the famously unprincipled diplomat Talleyrand, who must have learned from this mistake, given his later successes. Not everybody was like him. Cobbett, though, just had his existing beliefs reinforced—clearly the French revolution, and democracy in general, were just a cynical ploy by aristocrats.

The British government, too, began to take notice. They were grateful to this brave royalist, fighting the good fight behind enemy lines. A British diplomat tried to give him money, not as a bribe, just as thanks. He turned that down, too. But when he’d finally gotten too controversial even for America, he fled back to Britain, where, at first, he had a hero’s welcome. He dined with Pitt the Younger, the long-serving Prime Minister, who offered to put him in charge of a government newspaper. He declined, wanting to preserve his independence. By the next year, angry mobs were smashing his windows over his criticism of a treaty with France.

The treaty was the first of many disappointments for Cobbett. Pitt’s government was spending money on sinecures for upper-class people instead of paying their lower-class employees a living wage. He tried to run for Parliament, to help fix this injustice, but was foiled by the electoral system, which was rigged to a ludicrous degree to support the status quo. Boroughs so small that they had single-digit numbers of voters still sent two representatives to the House of Commons. Those representatives would typically include the landlord and/or people who bribed him. Even outside these “rotten boroughs,” other rich people bought seats by simply bribing all the voters—most people couldn’t vote, which made it affordable. Cobbett, of course, refused to engage in such tactics.

At the same time, Cobbett discovered that the writings of Thomas Malthus were becoming more and more influential. Malthus argued that any improvement to the lives of the poor would lead to catastrophic overpopulation and disaster. Cobbett recognized, correctly, that this was just factually wrong, in addition to being a horrific new way to defend the oppressive status quo. It must have been a terrible moment when he realized: he agreed with William Godwin about something. Despite still being a reactionary conservative in almost every way, this meant that he was a Radical.

In 1809, a small group of militiamen in Cambridgeshire tried to go on strike after a pay cut (in one version of the story, they’d been told that the costs of their equipment would now come out of their pay.) The army considered this a mutiny, court-martialed the lot, and sentenced five of them to five hundred lashes each. The story echoed the very first injustices Cobbett had witnessed and experienced in the army. He was too outraged to be cautious in how he wrote about the incident, and was promptly arrested for seditious libel. Now they decided to enforce that law?

During his two years in Newgate Prison, he discovered that he had, despite himself, managed to find allies. Not too long ago, he’d been calling for radical writers to be imprisoned. Now, some of those same writers visited him in prison, often with care packages. The radicals had gotten good, via long practice, at supporting each other while they did time. They understood that even if someone is your ideological opposite on 99% of issues, if they care about fighting oppression, they’re your friend. Godwin visited once a week for four weeks.

From that point on, Cobbett was one of them. He had a distinct advantage over many of the other populist writers: he was an actual commoner. He’d started off poor, and had refused every attempt to turn him into a class traitor. He sincerely agreed with the common man on issues none of his fellows could stomach: slavery of Africans was fine. Religious dissenters, Jews and Muslims were evil. Non-marital sex was a sin. Cobbett was able to reach, and radicalize, whole classes of people that nobody else could.

Even in his later writing, he remains comically unable to see anybody else’s point of view, to the point where it sometimes feels like he might be doing a bit. His Rural Rides has this gem:

Lord Caernarvon told a man, in 1820, that he did not like my politics. But what did he mean by my politics? I have no politics but such as he ought to like.

I think this is why he never really became liberal. Liberalism requires at least a little bit of ability to generalize from causes you support to causes you don’t. In Rural Rides, he complains about the chilling effects of censorship and calls for the atheist Susannah Wright to be released from prison. But in the same book, he rails endlessly against “the crafty crew of Quakers, the very existence of which sect is a disgrace to the country.” He even gives some helpful advice on how to sustain this kind of mental split:

Therefore, when I hear of people “suffering;” when I hear of people being “ruined;” when I hear of “unfortunate families;” when I hear a talk of this kind, I stop, before I either express or feel compassion, to ascertain who and what the sufferers are; and whether they have or have not participated in, or approved of, acts like those of [rival political writers] Jacob and Johnson and Brodie and Dowding; for if they have, if they have malignantly calumniated those who have been labouring to prevent their ruin and misery, then a crushed ear-wig, or spider, or eft, or toad, is as much entitled to the compassion of a just and sensible man.

Captain Swing

By 1830, Cobbett was writing that direct action, riot, and revolt were necessary and justified. If you didn’t own land, you couldn’t vote, so how else could your voice be heard? His readers agreed.

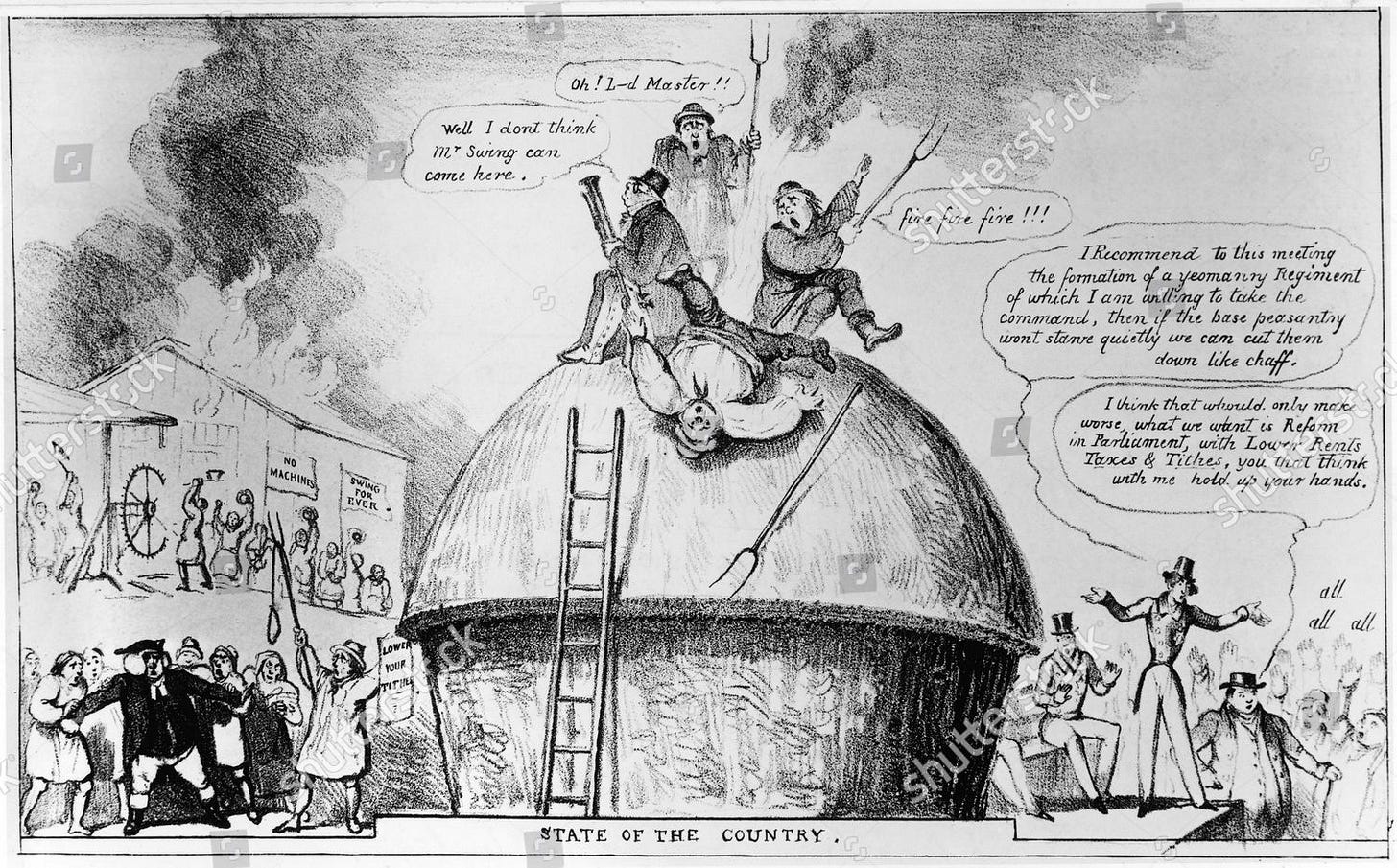

Local agitators began to write threatening letters to the powers that be, using the made-up name “Captain Swing.” Swing would demand higher wages, lower tithes, and often the destruction of threshing machines, which threatened the bargaining power of laborers. If the demands weren’t obeyed, hundreds of farmhands would show up and enforce them.

The “Swing Riots” exclusively targeted property. There’s no recorded case of them killing anyone. As violent revolutions go, this one was kind and cozy. Not that the government showed any mercy. Nineteen rioters were executed, almost five hundred were sent to Australia, and hundreds more were imprisoned. For defending Captain Swing in print, Cobbett was arrested for seditious libel yet again.

But things had changed since the last time he’d faced charges. People like Robert Carlile and Susannah Wright had been enthusiastic martyrs for the cause of freedom of the press, and the regime of censorship was crumbling. Like last time, Cobbett represented himself. Unlike last time, he won.

At the beginning of his political writing career, Cobbett was given the nickname “The Porcupine” by his American critics. He loved it, and wrote under that name whenever he could. A porcupine can stand its ground against a large predator, not attacking, just making it clear that it will not be moved, and will not be easy to kill. Only the most foolish predators end up slinking away bleeding, having tried and failed to call its bluff.

When Wellington announced in Parliament that he intended to continue to ignore Captain Swing’s demands, rioters showed up at his house the next day. Swing was suddenly everywhere at once, demanding, above all, the right to vote. It was clear to everyone, including the new king, which way the winds were blowing. After 44 years in the opposition, Grey and his populist mandate were finally able to take the reins.

Grey reformed the voting system, restructuring the boroughs to ensure they all had actual people living there, and greatly expanding the right to vote. Cobbett was delighted…at first. He was one of the first actual commoners elected to the House of Commons after the reform. (“I never saw so many shocking bad hats in my life,” complained Wellington). But he was still a porcupine. He didn’t like that Grey was spending so much effort and political capital on freeing the slaves—not when White laborers were still being oppressed. He also didn’t like how seriously Grey’s government was taking Malthus. Their Malthus-inspired 1834 “Poor Law” abolished the right to welfare in favor of a right to sell yourself to the brutal new workhouses. This betrayal finally broke him, and he died the same year.

It’s tempting to call Cobbett something like “the most unlikely Radical of his time.” He went from calling it “reprehensible” to befriend Charles Grey to helping to put him in power. In 1798, he wrote

How alarming must it be, to all true friends of religion and morality, to see Godwin's Political Justice and Volney's Ruin in the hands of even the country youth! In a country where this is frequent, no public happiness can be of long duration; no government, founded on principles of freedom, can long exist. Universal licentiousness must ensue, anarchy must follow it, and despotism must close the horrid career. This progress is inevitable. It is a wise and just sentence, the fulfillment of which every nation on earth has, at some time or other, experienced —that the licentious, the immoral, and the irreligious never shall be FREE.

By 1831, he was writing that Godwin had “more talent in his little finger than Malthus in his whole body,” and deserved a pension from the government. Who could have predicted that?

But I don’t actually want to frame him that way. Cobbett didn’t change, so much as learn a few things. You could look at him in his twenties, angry and taking a stand against class discrimination in the army, and have a pretty good guess at what would come next. The surprise, really, is that he never ever sold out. Fifty years later, he was fighting exactly the same fight, full of the same hope for justice.

The other reason Cobbett isn’t the most unlikely Radical of the period is that that honor definitely goes to the Queen of England.

A New Power in States

When Napoleon died in British custody, he had a lot of arsenic in his system. But the past is a terrible place where there are lots of innocent ways to end up with arsenic poisoning. We’ll probably never know for sure how it happened. What we do know is George IV’s reported reaction to the news. “Sir!” his chamberlain told him. “Your bitterest enemy is dead!”

“Is she?” George replied. “By God!”

The woman whom George feared more than the Emperor was Princess Caroline of Brunswick, to whom he was, theoretically, married. George didn’t really think of it that way. He had married for love before ever meeting Caroline. But his wife, Maria Fitzherbert, was completely unsuitable to be Queen—she was a commoner, had been married twice already, and, worst of all, she was Catholic, and therefore disqualified under law. So his father and the government just kind of pretended she didn’t exist. The marriage was an open secret, but still illegal to do more than hint at in the press.

Prince George then spent all of his royal allowance on luxuries, and asked for more. He was sternly informed that if he wanted more money, he needed to marry someone suitable and produce an heir. They had a queen picked out already: his first cousin Caroline, a princess in the Holy Roman Empire.

George sort of went along with this. He didn’t divorce Maria, but it was decided that that was okay: a royal marriage without the consent of the king didn’t count. George married Caroline and lived with her long enough to have a healthy daughter, then went back to Maria. In his will, he left Caroline one shilling. The rest he willed to “Maria Fitzherbert, my wife.”

Caroline took all this in stride. Her whole life had already been weird, even by the standards of royalty. From an early age, she was deemed too charismatic (“most amiable, lively, playful, witty and handsome”) to be allowed to spend time with men. Any time, with any men. Eventually, she was allowed to go to balls, but forbidden to dance. She occasionally protested by faking going into labor. To entertain herself in her isolation, she took up horseback riding. It was odd how long those rides tended to be. Thankfully, it took her guardians a long time to realize that she was riding her horse to peasant cottages, hanging out there, and probably canoodling.

When she was 26, Lord Malmesbury, an English diplomat, arrived to inform her that she was engaged to Prince George and escort her to England. After meeting her, Malmesbury was immediately a bit concerned. He wrote in his diary that she had “some natural, but no acquired morality,” “warm feelings, and nothing to counterbalance them,” a good nature but little tact. Also, he wrote, she often smelled of horses, and would slip into her peasant persona from time to time. The result of all that effort to keep her “pure” was that she’d grown up common.

But England needed the alliance for the fight with Napoleon. Malmesbury swallowed his doubts and introduced her to Prince George anyway, who acted cold and disgusted on their first meeting. “Mon dieu! Is he always like that?” she said, to nobody in particular. “I find him very fat, and not at all like the picture that was sent to me.”

After the two managed, with the aid of a lot of alcohol, to reproduce, they separated with an understanding that both were free to do as they wished. She had a lot of fun. When the Tory government tried to restrain her, she allied herself with the Whigs and reformers, which was mutually beneficial—they helped her propagandize against her husband, and she gave the leaderless radicals a figurehead.

Then George III died, promoting IV from regent to king. A prominent radical was now, officially, Queen of England. In a public address, she said “It is only the base and the cowardly that can tamely acquiesce in injustice and inhumanity…As the Queen Consort of England, my sphere of usefulness is small…but as far as my power or my influence extends all classes will ever find in me a sincere friend to their liberties and a zealous advocate for their rights.” This was unacceptable. A bill was introduced in Parliament to strip her of her title on grounds of adultery.

She joked in private that it was a fair cop—after all, she’d slept with Maria Fitzherbert’s husband. But she also saw the moment as an opportunity. She now had the right to defend her honor on the Parliament floor. The debates over the bill turned into a high-profile trial, with witnesses, cross-examinations, and stirring speeches by the defense. She framed it all as radicals versus oppressors. In particular, she argued that the trial was really over whether the government had a monopoly on truth. In a letter to a coalition of trade guilds, she put it this way:

My life will furnish a singular example of the native strength of truth and innocence. These have been my principal support against a host of enemies…assisted by a degree of corrupting influence such as no Government ever possessed before. But this enemy, so vast in might, and so unbounded in his means, has been vanquished by the force of truth, assisted by the liberty of the press…I strenuously exhort and earnestly request my friends in the north, as well as the south, never to lose sight of this truth—that Britons can never be enslaved while the press is free. Public opinion, which is a new power in states, and which is a salutary check upon every other power, owes its origin to the liberty of the press; and it is impossible for one to survive the other, or for liberty to exist when both are destroyed.

Stirring words, written and published with the help of the radical writers circle, including William Cobbett.

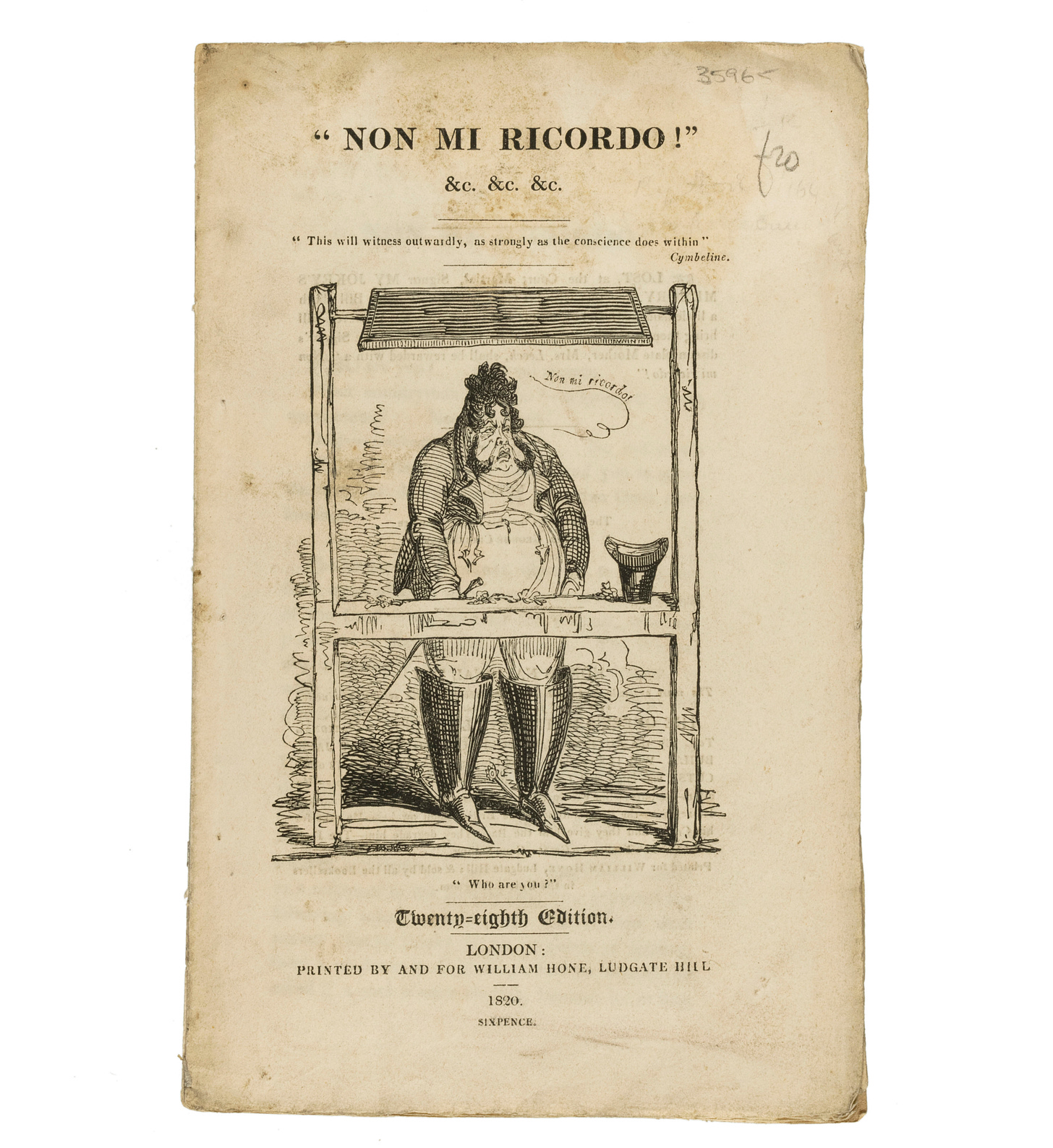

Her advocates in Parliament, meanwhile, succeeded in discrediting the prosecution’s star witness, who was reduced to answering “Non mi ricordo” (I don’t recall) to over 200 questions, including, once he was flustered enough, “Who are you?” The House of Lords passed the bill anyway, but the House of Commons made it clear that it had zero chance there, so it was withdrawn. There was celebration in the streets throughout London at this victory, with crowds chanting “Long live Queen Caroline”, “Non mi ricordo!” and “Rule Britannia!” She’d made it possible to be both patriotic and progressive, royalist and rebel.

Somebody may have gotten an idea from George, when he heard the news of Napoleon’s possible-poisoning and thought they were talking about Caroline. Soon after trying to crash the coronation, she suddenly took ill and died. Many assumed she was poisoned.

As with Cobbett, her radical turn is both surprising and inevitable in retrospect. “Some natural, but no acquired morality,” Malmesbury wrote of her on their first meeting. Kind-hearted, with no ideology or inhibitions to counterbalance it. Forced by circumstances and character into a state of constant revolt. She was always a revolutionary. As soon as it was in her personal interest to join a political faction, the radicals were a natural fit.

Non mi ricordo

People like Caroline and Cobbett are useful, probably essential, to revolutions as they happen. They provide a kind of social proof that the radicals aren’t completely detached from culture or reality. They legitimize. But they’re less useful to historical narrative, where movements are mainly legitimized by their success. Instead, we want explanations. We want to find causes in vast social forces or idealized characters—a pure villain for atrocities, an appropriate hero for victories. Princess Caroline and her alliance of convenience with democracy are neither inevitable nor thematically apt. Cobbett has trouble going more than a page without some viciously racist comment, usually out of nowhere—how does he belong to the story of how slavery was abolished?

We don’t even remember this one as a revolution. The system, to all appearances, remained intact. The people whose demonstrations and direct action forced Grey into power are called the Swing Rioters, not revolutionaries, and were condemned to obscurity and worse. William IV kept his head and his throne.

But the power shift was real and permanent. Public opinion chose Parliament, who chose their ministers, who, by and large, told the Crown what to do. When William tried to put Wellington back in power, the people protested until he backed down. When Parliament tried to “end” slavery by replacing it with mandatory unpaid apprenticeships, protests forced them to free the apprentices. By the end of William’s reign, he acknowledged that he had become a figurehead, saying “I have my view of things, and I tell them to my ministers. If they do not adopt them, I cannot help it. I have done my duty.” The monarchy became a mechanism by which the House of Commons neutered the House of Lords—if the Lords didn’t vote the right way, the Commons could tell the monarch to create some new lords.

And the leaders of the House of Commons could be commoners, or at least new rich. The days of the Duke of Wellington versus the Earl of Grey were over. Soon it was Benjamin Disraeli, son of a Jewish writer, versus William Gladstone, son of a plantation owner.

We forget the gentle-ish revolutions, the ones that, though forcible, shed little blood but their own. They fade obligingly into history and let the new establishment claim continuity with the old. This amnesia creates an illusion that the only instrument of lasting change is the sword.

So heed the lesson of the princess and the porcupine. The sword is mighty, but mightier is the quill.

Bonus: Radical Swedes

To dodge more prison time, Cobbett spent two years, 1817–1819, back in the States. This time he moved to Long Island, which at the time was still mostly farmland. When he returned to England, he had plenty of American agricultural innovations to evangelize along with his politics.

To hear him tell it, anyway, he’s basically singlehandedly responsible for every agricultural idea that got adopted across the pond. Because he was traveling through rural England preaching both radicalism and rutabagas, the two became linked—he claims in Rural Rides that farmers in Norfolk referred to rutabagas as “radical Swedes” (swede is British for turnip). So he invents a fun extended metaphor:

This is really the radical system of husbandry. Radical means, belonging to the root; going to the root. And the main principle of this system (first taught by Tull) is that the root of the plant is to be fed by deep tillage while it is growing; and to do this we must have our wide distances. Our system of husbandry is happily illustrative of our system of politics. Our lines of movement are fair and straightforward. We destroy all weeds, which, like tax-eaters, do nothing but devour the sustenance that ought to feed the valuable plants. Our plants are all well fed; and our nations of Swedes and of cabbages present a happy uniformity of enjoyments and of bulk, and not, as in the broad-cast system of Corruption, here and there one of enormous size, surrounded by thousands of poor little starveling things, scarcely distinguishable by the keenest eye, or, if seen, seen only to inspire a contempt of the husbandman. The Norfolk boys are, therefore, right in calling their Swedes Radical Swedes.

Cobbett would have hated me at every point in his evolution, for varying reasons. But I can’t help but identify with him here, advocating equality by way of elaborate analogies involving root vegetables and etymology. I might not be part of his crew, but he’s part of mine.

Definitely one of my favorites so far. Just incredible how much of history gets glossed over, so THANK YOU for bringing forgotten gems like this to light, and so beautifully. I can see the movie!