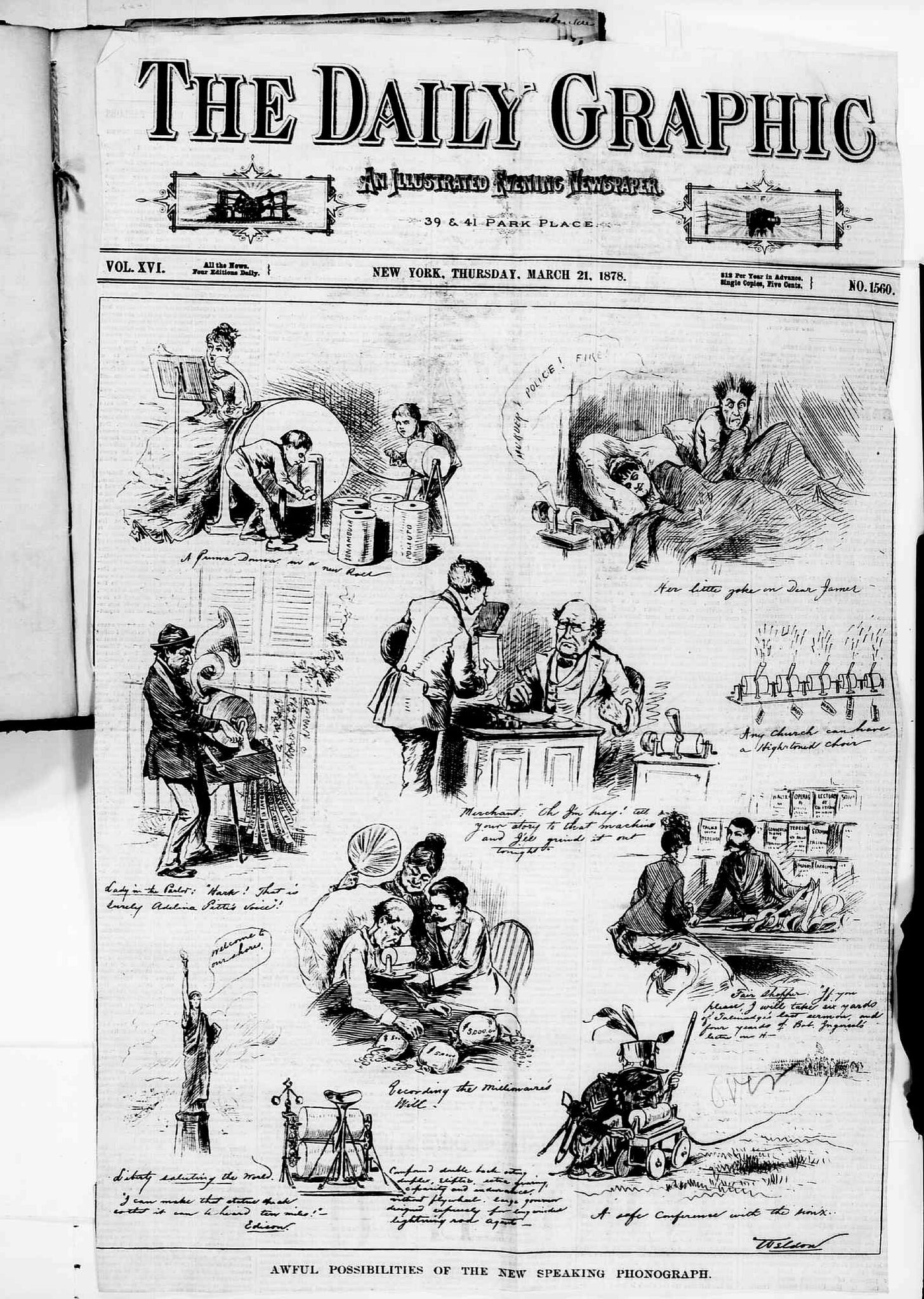

Awful Possibilities of the New Speaking Phonograph

What we got right and wrong about the invention of audio recording.

In America, it’s a time of technological advances and political regression. The Republican president, narrowly elected in a time of extreme polarization, is rolling back decades of civil rights protections and enforcing new restrictions on immigration. On the other hand, suddenly machines can impersonate humans in a way many believed was impossible. The year is 1878, and people are freaking out about Thomas Edison’s new invention that can speak with a human voice.

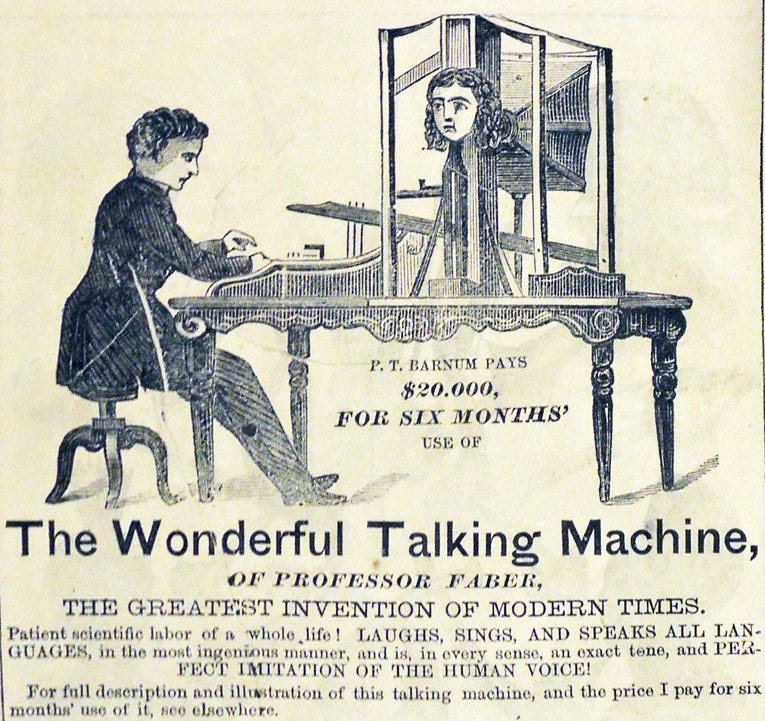

We were just getting used to the idea of a telephone. But that wasn’t a machine that spoke, it just relayed a human voice. To speak, many believed, a machine would need to perfectly replicate a human larynx and force air through it, something well beyond modern science. In 1842, the Austrian inventor Joseph Faber unveiled a valiant attempt at such a device, but you had to operate it by pressing a key for each syllable, which nobody could do fast enough to create realistic speech.

Although it was exciting at the time, thirty years went by without any substantial improvement, so the talking machine remained the stuff of carnival attractions and science fiction.

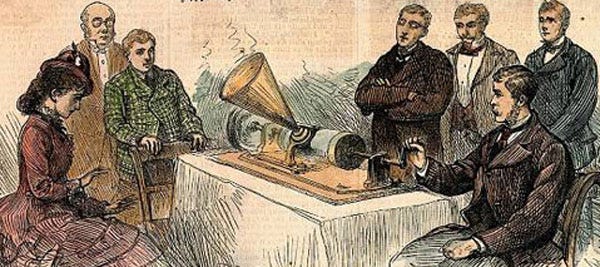

But in December of last year, Thomas Edison walked into the offices of Scientific American in New York City with a box that could be made to recite “Mary Had A Little Lamb” just by turning a crank. Edison had sidestepped most of the technical challenges that had limited inventors of the past. He didn’t try to replicate a human voice—rather he built a device that could record and play back any sound, vocal or no. This was, paradoxically, much easier—the former would require understanding human biology deeply and precisely, while the latter just required a good understanding of how sound works.

Ever since, there have been loud skeptical voices dismissing the story as a hoax or exaggeration. There’s been precedent—fake stories of Edison inventing a food synthesizer, or antigravity, or what have you, and also fake speaking machines that were demoed using a hidden ventriloquist. The French Academy of Sciences is reported to have been particularly difficult to persuade. More than one German news article announcing the phonograph included a note at the end emphasizing that this was not an “amerikanischen Humbug,” they had a reliable witness. Edison saved a letter from a New Haven professor telling him to repudiate the hoax before it damaged his reputation, as it was apt to fool ignorant people who didn’t realize the impossibility of such a device.

But this claim is pretty easy to prove, once you get the skeptic in the room with the box.

It’s hard to shake the instinctive belief, true for almost all of human history, that anything that can talk must be a person, or at least a very clever bird. Scientific American’s article starts off by giving a good, detailed, mechanistic description of the device, but then, at least for a sentence, gets a bit magical. “It is a little curious that the machine pronounces its own name with especial clearness,” they write.

They knew, on some level, that the machine was playing a recording of Edison in which he carefully enunciated the name of his new invention. But their gut wanted to believe that the machine might be self-aware. “No matter how familiar a person may be with modern machinery and its wonderful performances,” they write, “or how clear in his mind the principle underlying this strange device may be, it is impossible to listen to the mechanical speech without his experiencing the idea that his senses are deceiving him.”

Laypeople seeing the phonograph operate for the first time tend to attribute magical powers to it. “Can it tell my fortune?” some ask. (Barnum and his ilk answer “yes, for an additional fee.”) Others tend to assume it must be powered by something newfangled, the electricity Edison is so associated with, or at least steam. Surely something so wondrous can’t be purely mechanical.

In fact, the phonograph can do something traditionally considered black magic. People, starting with that first Scientific American article, have been quick to point out that we will now be able to summon the voices of the dead.

Predictions haven’t stopped there, of course. It’s 1878, after all — we’re getting pretty good at figuring out the implications of this sort of thing, having witnessed as many as several new inventions already.

Every would-be diva will record her voice. People will prank, scam, and surveil each other. Businesses will make you leave a message for them to listen to when they’re less busy. Any church can have a high-toned choir. Wills will be recorded in order to authenticate them. Music will be bought at the store as a commodity. Peace negotiations will happen at a distance, for safety. Edison himself has proposed that when the Statue of Liberty is installed in New York harbor, we could include a giant phonograph in her head so that she can say “Welcome to our home” to incoming ships.

Others extrapolate further, speculating about combining the recorded sound with some sort of visual recording, to create a perfect counterfeit of a human. And some, like the Universalist minister James Harvey Tuttle, see the phonograph as the latest piece of evidence of the coming universal transcendence of mankind, one in which all of us will have access to all of civilization’s knowledge and wisdom.

… there is ground for believing that the whole race will finally be brought up to the highest mark yet reached by the greatest mind. There is more probability now that all men will become Bacons intellectually, and St. Johns morally and spiritually, than there was once that one man would ever become a Bacon or a St. John. What could have taxed human credulity more severely than the promise of the printing press, the steam engine, the telegraph, and last, and most wonderful of all, the phonograph. Are we to halt in our hope of human nature after what we have seen? Are not man’s capabilities absolutely unlimited?

That was how it looked in 1878. Here in the present day, it feels like the wild speculation was all pretty accurate. We didn’t end up using audio recording for authenticating wills. I assume somebody pointed out that it’s not necessarily harder to forge a voice than a document. The Statue of Liberty has not (yet) been turned into an animatronic robot. But the rest of it—the bad, the good, the weird—we know that it panned out more or less as predicted.

Eventually. But on shorter timescales, it was the skeptics who were right. Edison struggled to monetize the phonograph. He was stuck, like the rest of the world, on vocal recording, when actually instrumental music was the killer app. Low-fidelity voice recordings fall into the uncanny valley—too humanlike, and not humanlike enough. The talking dolls Edison made were just creepy and nobody bought them. The “gramophone,” which played music from discs, wasn’t invented for another ten years, and it wasn’t Edison who invented it, but his rival Emile Berliner.

Technological unemployment was another area where the skeptics were (temporarily) right. Stenographers were panicked, at first, thinking that all of their shorthand knowledge was about to be obsolete. Others pushed back, arguing that shorthand was always going to be better than audio because the reporter “has exercised discrimination as to what should be taken or omitted for his purposes.” Their arguments were bad, but they were accidentally right for almost a hundred years—the tech just didn’t get good (small, easy to use, high quality) fast enough to put anybody out of work.

In his 1963 essay on artificial intelligence, Hugo Steinhaus briefly touches on the response to the phonograph as a historical analogy. After reading more about it, I think the phonograph is a pretty apt comparison. We’re too fixated, at the moment, on having AI imitate human writing and human speech. It’s basically the same mistake for the same reason—imitating humans is magical, everything else is more mundane, so surely the magical part is the important part? Edison had his creepy dolls. We have millions of AI models trained to write like the same sycophantic personal assistant.

We both underestimate and overestimate AI when we think about it as imitating human thought. It’s not. It’s doing something weirder. Skeptics correctly notice that it’s not really thinking in any human-like way, even though it’s producing human-like output, and then incorrectly declare that that means the whole thing is a humbug ventriloquist act. More credulous people end up believing an AI’s report of its own feelings and thought process, deluding themselves that they’ve awakened, or discovered, self-awareness in their new friend.

“The phonograph can record and play back any sound” came across as less magical than “it will summon the voices of the dead.” But the one implies the other. In generality is power.

I don’t know when we’ll have machines that actually think. But we have machines that can take arbitrary input and process it into arbitrary output by recognizing patterns. That sounds less magical, but that can be deceiving. The possibilities are awesome, and awful, and you’d better believe they’re coming.

I’ve always dreamed of one day becoming a Bacon!