Did Charles Dickens Burn Down Parliament?

It will be irresponsible to speculate.

I know I’m not the only one who wonders if great fiction writers are secretly also master criminals. They’re always coming up with plausible ways that something could go horribly wrong—it’s called a “plot” for a reason.

At Charles Dickens’s level, I’d expect something truly spectacular. Say, destroying the seat of power of his own government and making it look like an accident, with the truth never uncovered.

So where was he on the night of October 16th, 1834?

The Official Story

Charles Dickens had a lifelong interest in the mechanics of how things burn. His periodical, Household Words, included cutting-edge popular science articles on the nature of fire. He’s suspected to have written them himself. He studied records of spontaneous human combustion, decided they were definitely real, and used one to kill off a character in Bleak House. (I won’t list all of the Dickens characters who died in fires. Spoilers.)

And, in 1855, he gave a speech describing the exact chain of errors that lead to the Palace of Westminster, home of Parliament, burning down in 1834. Here’s how Dickens says it went down.

The Palace had been the home of Parliament ever since it first met in 1295, and as such had accumulated a lot of odd traditions. One of them was that the office of the Exchequer, the accounting department of the government, kept some of its records there, not using ink and paper, but “tally sticks,” little pieces of wood with notches to represent different amounts of money. They’d finally decided to cut over to modern paper technology, but migrating all the data took decades, during which they held on to all the tally sticks, just in case. When they were finally ready, they had wagonfuls of the things to dispose of. While there was talk of giving them away for use as firewood, they theoretically had sensitive financial information on them, so instead they were burned on-site. Specifically, they were loaded into a coal-burning stove used to heat the floor of the House of Lords.

One problem with this plan was that wood burns differently from coal. The stove and chimney were designed for a slow burn, while wood burns hot and fast. The copper lining of the flues melted, and the flames licked higher into the chimney. The people loading the sticks in didn’t realize anything was going wrong. As soon as they’d incinerated all of the records, they left to go have a pint at the Star and Garter. The fire escaped into the House of Lords, then the House of Commons, and soon the whole building was a loss.

The moral of the story, Dickens says, is simple.

Now, I think we may reasonably remark, in conclusion, that all

obstinate adherence to rubbish which the time has long outlived, is

certain to have in the soul of it more or less that is pernicious

and destructive; and that will some day set fire to something or

other; which, if given boldly to the winds would have been

harmless; but which, obstinately retained, is ruinous.

The whole thing was a metaphor for the folly of conservatism, in other words. The rest of the speech is overtly political, calling for Administrative Reform.

Dickens, curiously, leaves out one little detail: he was probably there when Parliament burned.

Dickens’s Day Job

In 1834, Charles Dickens was 22 years old. He’d gotten a few short stories published, but hadn’t had his big break yet. It would take another three or four years before he’d become an immortal international celebrity. To make ends meet, he’d just started reporting on Parliament for the Morning Chronicle. He worked hard, but he hated it. He didn’t like anybody in Parliament, other than the people who ran Bellamy’s, the cafeteria. And the institution as a whole seemed like a corrupt and dysfunctional barrier to progress.

The Morning Chronicle published multiple accounts of the fire, all attributed to a single “our reporter.” The reporter is never named, which wasn’t unusual. It was probably Dickens, though. It was his beat, after all, and finally something exciting was happening. Why wouldn’t he be there?

It’s hard to solve this with textual analysis—the story might have been heavily edited, or even written up by one reporter using another’s account. Dickens’s voice wasn’t fully formed yet, and of course he’d be writing differently when reporting on a national tragedy. Still, I want to highlight one passage from “our reporter:”

The scene without the walls of the Tower was almost as wild as within. The gates were actually besieged, and the glare of the conflagration showed Tower hill alive with multitudes gazing horror-struck upon the scene before them. Vague but fearful stories began to circulate among them of gunpowder stored in the Armory. The idea was terrible. Rumour said that thousands of pounds were kept there—a frenzy of alarm was excited, and for many hours it was believed that in another moment the whole Tower might be blown to atoms. Fortunately these rumours were untrue; no gunpowder was kept in the burning buildings.

And here’s a passage from Bleak House:

“There never was such an infernal cauldron as that Chancery on the face of the earth!” said Mr. Boythorn. “Nothing but a mine below it on a busy day in term time, with all its records, rules, and precedents collected in it and every functionary belonging to it also, high and low, upward and downward, from its son the Accountant-General to its father the Devil, and the whole blown to atoms with ten thousand hundredweight of gunpowder, would reform it in the least!”

It was impossible not to laugh at the energetic gravity with which he recommended this strong measure of reform.

The Chancery in question is part of the same building as Parliament.

Getting the Gang Together

There’s no way Dickens pulled this off alone. To engineer the apparent accident, obvious metaphor and all, you’d need someone in a position to sabotage the chimneys, someone to ensure that the wood was disposed of in a very specific manner and time, and ideally someone on the scene to ensure the fire wasn’t discovered too early, thwarting the plan, or too late, endangering the servants.

The Saboteur

Who was in charge of the chimneys in the palace? Bizarrely, it was known anarchist William Godwin. Godwin’s publishing company had never turned a profit, so he’d become reliant on his daughter and son-in-law, Mary and Percy Bysshe Shelley. With Frankenstein money and Percy’s patience both running low, the once-famous author and philosopher had hit hard times. Fortunately for him, in 1830 the Whig party won control of Parliament, and named as its Prime Minister Charles Grey, a friend and devotee of Godwin’s. Grey did not waste this opportunity. In less than four years in office, he abolished slavery, granted suffrage to middle-class men, and created Durham University, breaking the 600-year-long duopoly of Cambridge and Oxford. (Also, Grey was an earl, so he might be the namesake of Captain Picard’s favorite tea.)

Grey’s government had granted Godwin a sinecure, a quasi-job that was mostly an excuse to give him money. This was a common practice at the time, and part of the reason procedures took so long to change—you don’t fire people with sinecures. The wooden tally sticks, for example, couldn’t be dispensed with until the person in charge of them died of old age. Godwin was made “Office Keeper and Yeoman Usher of the Receipt of the Exchequer,” which entitled him to a room in New Palace Yard (steps away from the Parliament building), 200 pounds a year1, and minimal actual responsibilities. Just, you know, routine maintenance. Including overseeing the sweeping of the chimneys.

An investigation afterwards found that the chimneys, darn the luck, were just about due for their annual sweeping when the fire happened. On top of this terrible timing, there had been holes cut in the walls of the chimney, apparently by chimney sweeps who wanted handholds and footholds as they climbed up and down. So the chimney had been turned into a pretty efficient mechanism for turning a small fire into a large one. People joked that Godwin had succeeded where Guy Fawkes had failed.

Did Dickens and Godwin know each other? It’s plausible. Dickens, as both an advocate for the poor and an aspiring novelist, would certainly have been interested in meeting the author of Political Justice and Caleb Williams. (We know from his correspondence with Edgar Allan Poe that he was a superfan of Godwin’s.) They worked in the same palace complex at the same time, so there would have been ample opportunity.

Godwin kept a meticulous diary of everyone he ever interacted with, but didn’t always get their full names, and didn’t always see fit to record them when he did. While his patron Charles Grey gets referred to as “Grey,” there’s one or more unidentified people he calls only Charles. Or, in an entry from nine months before the fire, “Charles ——”.

The Inside Men

If the official story has any connection at all to reality, any conspiracy would almost have to have included Richard Weobley and/or John Phipps, a clerk and assistant surveyor at the Department of Woods and Forests. These were the two, according to the official report afterwards, who made the fateful decision to burn the tally sticks on site during a recess, in order to clear space for a temporary office. Weobley was also one of the first people to sound the alarm, telling people he’d seen a chimney that was “very much on fire” and they needed to evacuate. You’d also want to take a look at “Mrs. Wright,” the deputy housekeeper, who, an 1836 book says, displayed “the most gross negligence” by not alerting the authorities until it was too late.

There’s no particular reason to expect a connection between any of these three and Dickens. Godwin, though, might easily have crossed paths with them—they were doing some of the actual work that constituted Godwin’s mostly-fake job. So, heading to Godwin’s diary, did he ever meet with anyone of that name?

Yep, in 1833, he gets a visit from “Phipps and Webley.” The “o” in Weobley is silent, so it’s plausible he’d miss it—he doesn’t always spell people’s names right.

There are actually two 1833 entries with an unidentified “Phipps” in the diary. The other one has an intriguing note in parentheses:

Less than a week before the “Phipps and Webley” entry, we see him calling on “Waller & Phipps, (Woods and Forests).”

So Godwin did have some dealings with the Department of Woods and Forests, in connection with someone named Phipps, and also probably someone named Webley. And I guess they kept in touch after, judging from this line from 1835:

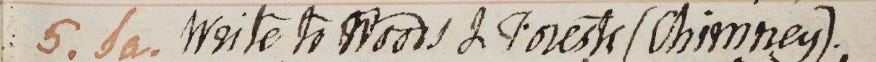

“Write to Woods & Forests (Chimney).”

A Mrs. Wright shows up in the diary too, in February of 1834.

“Woods & Forests: Mrs. Wright and Aldis call.”

Aldis is almost certainly Sir Charles Aldis, who is known to have played a sneaky trick on the government. Godwin and Aldis were also together, says the diary, on the evening of the fire.

Motive

A secret act of terrorism is usually an oxymoron. In this case, though, it makes some sense. The symbolism of the incident was just too obvious. Parliament had stuck to obsolete rules for far too long, declined an opportunity to help the poor by letting them take the wood home, and then burned themselves down with it instead. Dickens frames it that way in his speech, but he was hardly the first.

Unlike the Gunpowder Plot, which would have blown up the building while Parliament and the King were inside, this wouldn’t have been intended to be a decapitation blow to the state. Weobley and Wright made sure none of the servants died, either. There is one death, though, on the consciences of the hypothetical conspirators: a fireman crushed by a falling rock.

Why You Shouldn’t Believe Me

I haven’t lied or deliberately misled at any point in this article. But I’ve committed a grave epistemic sin. The conspiracy theory occurred to me, not on the basis of any evidence, but just because it’d be such a fun story to think about. Then, I went looking for evidence for it. Whenever you look for evidence for a conspiracy, you typically find it.

This is a fallacy of privileging the hypothesis. There were about 2 million people living in London in 1834. I picked Dickens and Godwin to accuse because they’re famous, which makes the story more interesting and easier to research. The odds of that process picking the correct two people are at best one in a million, even supposing there were any conspirators at all.

These kinds of tricks are how you get smart, literate people to fall for disinformation. You pick a story that gets the blood pumping and can’t be easily disproved. Then you can present an endless series of true facts that, in light of the story, look like they could be part of it. Now your disinformation can be independently verified! Every bit of it could be true…except for the implied claim that you wrote it in response to the evidence, instead of the other way around.

The only part of this theory of mine that I actually endorse is that the unidentified Phipps and Webley in Godwin’s diary are the same two people who would shortly be blamed for the fire. That conclusion, for me, came from properly looking at the evidence. (I’d actually been hoping Phipps was someone else, politician and novelist Constantine Phipps, but while I haven’t ruled him out, he makes much less sense). I don’t think it’s that weird that Godwin had meetings with Woods and Forests, though—they had overlapping responsibilities. If anything, it’s evidence that they were trying to be conscientious about their jobs—they failed catastrophically, but not out of complete apathy.

If Dickens can use the fire as a metaphor for the dangers of haphazard conservatism, I suppose it’s fair play to use it as an illustration of the dangers of haphazard reform. The Palace was rebuilt according to the same plan, and still houses Parliament today. Burning it down and rebuilding it, in the final analysis, took money out of the hands of the needy. The tally sticks needed to be disposed of, sure. But burning them hastily, under the auspices of people who may not have been totally invested in avoiding damage, was a terrible mistake.

For reference, one of Grey’s reforms was to say that anybody who paid at least 10 pounds a year in rent was rich enough to vote.

Do you think that DOGE's attempt to hastily migrate SSA systems off COBOL into JAVA or whatever will cause an analogous Dickensian fire?