Don't Take Medical Advice From Porcupines

Potatoes do not cause scrofula.

Populism has a mixed relationship with public health. On the one hand, the very idea of caring about public health is an inherently populist one. Plus, other historically populist causes—housing, workers’ rights, government benefits, and so forth—also tend to improve public health. Better housing and working conditions means you get sick less, and a social safety net helps you when you do.

On the other hand, public health is complicated and confusing. Anybody who can talk about it with any sort of rigor is, just about by definition, an Expert. An Elite. One of the bad guys.

So we often end up with movements that combine

A clear-eyed and compassionate view of the problems the system tries to sweep under the rug.

Horrifically bad takes on the solutions.

These dynamics don’t seem to have changed that much over the past 200 years. In the 1820s, William Cobbett argued, in defiance of both expert opinion and reality, that potatoes were not fit for human consumption. In the 2020s, his spiritual successors argue that the pandemic is fake and vaccines cause autism…and at least one of them also believes Cobbett about the potatoes.

1. Potatoe-mania

I came to the potato thing because I was curious about the relationship between William Cobbett, the compulsively contrarian writer nicknamed “The Porcupine,” and Sir Charles Aldis, a doctor who studied treatments for scrofula. They have extremely different vibes, but they had plenty of friends in common, and both played a role in the reforms of the period. So I did a search to find out what Cobbett thought about scrofula. His answer? It was caused by potatoes and capitalism, and you could cure it with Dr. Morison’s Vegetable Pills.

Cobbett has quite a bit to say about the potato, usually as a symbol of the oppression of the working man. He blamed it for quite a few syndromes.

…accursed potatoes, and all their natural consequences, poverty of blood, leprosy, scrofula, pottle-belly and swelled heels!

This surprised me. Cobbett was, in general, a fan of growing and eating root vegetables, even non-native ones. But he was fiercely anti-potato, for reasons that were kinda evidence-based. Potato-eating probably really was correlated with scrofula, leprosy, and whatever those other things are. Nonetheless, it was being promoted by elites as a subsistence crop for the working class.

The actual reason for the correlation was simply that poor people grew and ate more potatoes than rich people. Potatoes can be grown on tiny plots of land, don’t need to be harvested at specific times, and don’t need a mill like wheat or barley. They’re uniquely dense in calories among crops with these features. With the Napoleonic wars putting a strain on the food supply, potatoes were a lifesaver.

Of course, people did point out all that to Cobbett. Many times. It only made him angrier. In order to justify his feelings, he needed to refute the economics. Potatoes simply couldn’t be as efficient a crop as people were saying. Here’s him doubling down in 1819, starting with a remarkably frank epistemic status warning:

It’s a long and detailed chapter. He spends a while explaining that the popularity of potatoes is an irrational fad. “Potatoe-mania,” he calls it. Just like the thing where people think Milton and Shakespeare are good.

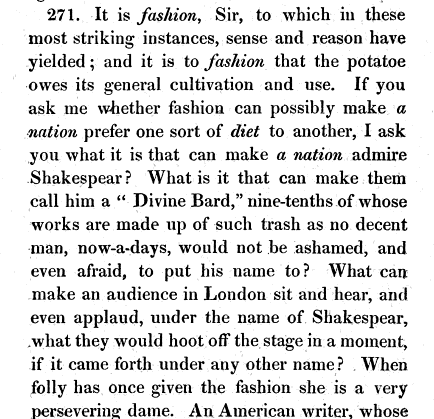

But then he gets to the crux of the issue—the claim that potatoes provide more calories per acre than grain. This can be disproven with some simple arithmetic.

So potatoes theoretically provide very slightly more food per acre, he says, but when you factor in the extra labor to prepare them, compared to baking bread, it’s clearly not worth it. Not unless you want to prepare them the easy Irish way, which no self-respecting English person ever would. I can’t imagine why Irish people took offense at this description:

For it must be a considerable time before English people can be brought to eat potatoes in the Irish style; that is to say, scratch them out of the earth with their paws, toss them into a pot without washing, and when boiled, turn them out upon a dirty board, and then sit round that board, peel the skin and dirt from one at a time and eat the inside.

There’s a lot going on here, but the main bit of sleight of hand in Cobbett’s math is fairly subtle. He uses ideal, best-case yields for both wheat and potatoes, which seems like it should be fair. But the variance for wheat yields was much higher. The amount of wheat you can grow depends heavily on the soil quality, weather, and your own capabilities. An average wheat yield would have been less than half of the 40-bushel ideal yield. Much less, in some regions—data from the U.S. in 1866 gives an average yield of a mere 11 bushels per acre. In contrast, the average yield of potatoes (before the Famine) would have been about 5 or 6 tons per acre pretty much anywhere you could grow them.

This means that by comparing best-case yields, rather than average yields, Cobbett is understating the potato advantage by a factor of around 2—average yields for wheat are a quarter of the best case, while average yields for potatoes are half of the best case. Double those potato yield figures, and potatoe-mania suddenly makes sense.

That’s one way to see through this argument. There’s also the more common-sense, non-mathematical way, which is to note the utter absurdity of Cobbett’s claim that potatoes are a global mass delusion. This is load-bearing—he needs some explanation for why South America, Ireland, Spain, Prussia, and now England and Eastern Europe were all planting potatoes, other than it being a good idea.

It’s bad luck for Cobbett that his big example of an irrational fad is Shakespeare. But let’s give it to him. Let’s stipulate that the English love of Shakespeare is divorced from the merits of his work. It’s still not a strong enough example. The Incas weren’t into Shakespeare. Spain wouldn’t have a translation of King Lear for another forty years. Poland had actually just banned Shakespeare in 1830, when some of these essays were written. Humanity was not a monoculture back then, not even close. So how could all these very different cultures have been making the same mistake?

Plus, if potatoes were so bad for you, the countries that adopted them should be noticeably malnourished, and ultimately weaker. The reverse appeared to be the case. Prussia under Frederick the Great, for example, went all-in on potatoes, and then proceeded to conquer a vast empire. Ireland, despite being poorer than England, had a healthier working class.

(The correct criticism of potatoes, of course, would be that over-reliance on a single crop propagated by cloning was just asking for a devastating blight. Cobbett doesn’t manage to find that one.)

So to believe Cobbett, you need to have a specific approach to truth. He says that potato-pushing elites are fools or liars, and that the masses are gullible sheep. So you need to be someone who thinks critically about the claims made by authority, and about popular wisdom. You need to be able to follow, or think you’re able to follow, a mathematical argument. And then you need to suspend all of that critical thinking while reading Cobbett. You need to get to the point where you’re like “wow, Cobbett and I are the only people in the world who get it” and then not see any reason to be skeptical of that conclusion.

Are there really people like that?

2. Cobbett’s new convert

Meet Brad Pearce. I found him by googling something like “why did Cobbett hate potatoes,” so arguably this isn’t a fallacy of nutpicking, at least when applied to the potato controversy. Also, he has five times as many subscribers as I do. This is a Kind of Guy.

Pearce seems to be my age and general demographic, and something like a New Right version of me. When I first read William Godwin’s Thoughts on Man, I was moved and amazed. It felt like I was seeing what would happen if I became the kind of writer I aspire to be, and then was sent centuries back in time, where my modern liberal views made me an extreme contrarian. I wrote a blog post titled Meet William Godwin, the 18th-century philosopher who was right about everything.

Pearce had that reaction to William Cobbett. His first article about him was titled William Cobbett: the Original New Right Shitposter, which doesn’t sound complimentary until Pearce explains that he is also a New Right Shitposter. “Was this guy not absolutely one of us?” he writes. “It is undeniable that if William Cobbett were alive today, he would be among the best shitposters and best Substackers out there.”

In his followup post, William Cobbett vs the Potato: The Lone Voice Against a Deadly Elite Consensus, he gets to what he really wanted to talk about. Pearce went into reading Cobbett believing the standard line about them, but Cobbett opened his eyes.

“Potatomania” first took off in the mid-18th century, but despite periodic food shortages, the true impact of the policy wasn’t seen for around 100 years, and when it was seen, it wasn’t understood. Millions of people died because the elites believed the poor should eat potatoes, that era’s version of “You will eat the bugs.” The very premise of changing the diet of the poor to potatoes was never discredited among the elites, as shown by the fact that as recently as 2008 the United Nations declared “The Year of the Potato” based on the same beliefs about the potato’s utility for solving food insecurity. I believed this myself most of my life, that the potato was unique among the crops for its ability to produce an astounding amount of calories in a smaller space at a lower cost than grain. I must admit I believed this despite the fact that it is easily disproven by buying a 5 pound bag of flour and a 5 pound bag of potatoes- at roughly the same cost- and preparing both of them for consumption.

One man, did, however, bravely stand against the potato promoters: William Cobbett, the publisher of the Political Register and the father of alternative media. Cobbett laid out a clear, rational, mathematical explanation proving that potatoes simply did not provide the poor more nutrition at a lower cost than wheat- even before blight.

Pearce is actually correct that he can get more calories-per-dollar from flour than from potatoes. But that’s because he lives in the modern-day American midwest. The Green Revolution of the 20th century has finally allowed wheat to pull ahead. Once you consistently get close-to-best-case yields, Cobbett’s potato math starts to actually work. Not that the U.N. was wrong—the areas experiencing food insecurity are, naturally, precisely the ones where American-style agriculture doesn’t work, due to climate, infrastructure, or the thing where it’s a lot easier for warlords to seize all your harvested grain than for them to dig up all of your potatoes.

(Also, crop rotation is a good idea almost anywhere, and potatoes are great for that.)

But Pearce believes him. He loves the image of Cobbett as a correct contrarian pluckily persevering against the unreasoning scorn of the sheeple, who don’t even bother to engage with his clear, rational, mathematical arguments. Exactly the writer Pearce hopes to be.

And Pearce is, indeed, comparable to Cobbett in the quality of his clear, rational, mathematical arguments. Here he is a couple years ago, in an article titled A Pandemic Literally has not Occurred:

Usually, since Branch Covidians are immune to science and data, I simply refuse to play their game with these numbers. This goes along with my belief of calling them retards and moving along with your day. But the charts are still good for lulz, and since they allegedly based policy on them, for all of history it will fuck them that their extremely repressive measures have absolutely no correlation with disease data these very idiots produced.

Here are some current snapshots from WorldOMeter, one of the more innocuous groups to clearly make vast profits off of this scam. I have to admit, I’ve had their page open as a background tab for basically two years straight.

There are two things that basically any logical person who has been alive could see from this. The first is that, with a population of almost 8 billion people, just under 6 million dying in more than two years is hardly any sort of drastic number, and is fact not even notable. A calculator tells me that is .0739% of the global population. That is well under 1 in 1000 people globally, once again over the course of two years.

6 million people dying is “not even notable”! It’s just simple math. (Pierce, to his credit, is currently condemning the ongoing genocide in Gaza, which threatens to kill a mere 2 million people.)

But the tired old trick of dividing a number by 8 billion to make it smaller isn’t his main argument. It’s this:

And the average covid death age is the same age as the general death age, meaning that a positive covid test is not associated with increased mortality. Because the tests are faulty and if they do work it is a fucking cold anyhow. [And don’t give me shit about how every death is tragic. Human mortality itself is inherently tragic, but the elderly dying of infectious respiratory disease is just life.]

“The average covid death age is the same age as the general death age” is a superficially persuasive statistic. I, at least, had to stop and think it through to work out why it wouldn’t mean what Pearce thinks. Here’s a hint: if we executed everyone on their 30th birthday, the average death age would be very close to 30, because almost everyone lives to 30. The same argument would then prove that executions are not associated with increased mortality. Or, to use maybe a more precise analogy, suppose a potato blight killed some of your potatoes, but many of them were at risk of going bad soon anyway. That’s still a blight. You would still have fewer potatoes.

3. Stars aren’t real

It has never before occurred to me to be proud of this, but I did not make the same mistake when reading Godwin. The third-to-last chapter of Thoughts on Man is a clear, rational, mathematical debunking of…astronomy.

Picture me reading this book, with actual honest-to-God tears in my eyes at how wise it all is, and then, almost at the end…

“The sun,” we are told, “is a solid body, ninety-five millions of miles distant from the earth we inhabit, one million times larger in cubic measurement, and to such a degree impregnated with heat, that a comet, approaching to it within a certain distance, was by that approximation raised to a heat two thousand times greater than that of red-hot iron.”

It will be acknowledged, that there is in this statement much to believe; and we shall not be exposed to reasonable blame, if we refuse to subscribe to it, till we have received irresistible evidence of its truth.

…

Before we affirm any thing, as of our own knowledge and competence, respecting heavenly bodies which are said to be millions of millions of miles removed from us, it would not perhaps be amiss that we should possess ourselves of a certain degree of incontestible information, as to the things which exist on the earth we inhabit. Among these, one of the subjects attended with a great degree of doubt and obscurity, is the height of the mountains with which the surface of the globe we inhabit is diversified. It is affirmed in the received books of elementary geography, that the Andes are the highest mountains in the world. Morse, in his American Gazetteer, third edition, printed at Boston in 1810, says, “The height of Chimborazzo, the most elevated point of the vast chain of the Andes, is 20,280 feet above the level of the sea, which is 7102 feet higher than any other mountain in the known world:” thus making the elevation of the mountains of Thibet, or whatever other rising ground the compiler had in his thought, precisely 13,178 feet above the level of the sea, and no more. This decision however has lately been contradicted. Mr. Hugh Murray, in an Account of Discoveries and Travels in Asia, published in 1820, has collated the reports of various recent travellers in central Asia; and he states the height of Chumularee, which he speaks of as the most elevated point of the mountains of Thibet, as nearly 30,000 feet above the level of the sea.

This argument did not, thankfully, turn me into an astronomy skeptic. Maybe that means I’m better at critical thinking than Pearce. Or maybe I’m just irrational in a different way than he is. Pearce, I think, wants to live in a world where scientific consensus can be debunked by a simple, intuitive argument using the scientists’ own data, and yet inexplicably everyone goes on believing it anyway. The worse the rest of humanity is, the better he is in comparison. I, conversely, want to see farther by standing on the shoulders of giants, so the idea that all of astronomy is wrong is upsetting. I’d feel diminished by that revelation, not glorified. That difference in attitude is probably why we fell in love with two very different contrarian cranks of Georgian England.

Just in case, I’ll spell out the problem with this math: thinking the 20,000-foot-tall Andes are the tallest mountains in the world, when it’s actually the 30,000-foot-tall Himalayas, means underestimating the highest heights by 50%. That’s a lot, but it’s nothing like the multiple-orders-of-magnitude error Godwin is implying astronomers might be making. If the sun were ten times larger or smaller than we thought, that would be an equivalent error to thinking the 3,000-foot-tall Burj Khalifa skyscraper is bigger than Mount Everest. (Anyway, it is often easier to see your neighbor’s roof than your own, so why would it be weird for astronomy to be more precise than geology?)

I’ll count it as a win that Godwin’s star denial probably didn’t kill anyone.

4. Getting yellow-pilled

What made Cobbett such an effective advocate for the much-needed popular revolts of his time is that he didn’t really feel a need to avoid getting his readers killed. This is, as best I understand it, part of the Shitposter Ethos—you fling out an argument and move on, without stopping before, or after, to think about the result. It’s about being Rational in an exclusively vibes-driven sense that doesn’t have much to do with trying to improve your own thinking and be correct more often.

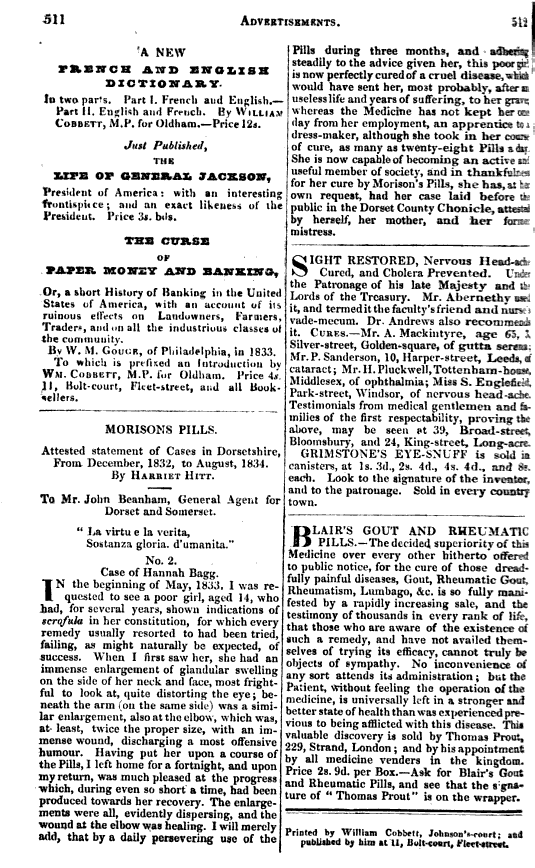

Cobbett’s political articles were supported by ads like these:

In doing so, he quasi-endorsed products that were at best snake oil and at worst poison. The “Morisons Pills” advertised here as a cure for scrofula (as well as everything else) were mainly made from gamboge, a yellow dye that is a laxative in small quantities and deadly in large ones. If 14-year-old Hannah Bagg had really taken 20+ pills a day for three months, she’d have gotten a larger dose of gamboge than the one that killed a 32-year-old man in 1836. That would’ve cured all her illnesses, in a way.

Unsurprisingly, he was also an anti-vaxxer. I don’t even want to bother quoting his arguments—you can just take an anti-vax essay today (Pearce has a few) and find/replace COVID with smallpox, and you’ll get the idea.

Potato hesitancy may have made the famines of the period worse, but arguably it also saved lives by preventing more countries from suffering Ireland’s fate. The medical stuff is more unambiguously bad—we can be pretty confident Cobbett’s willingness to signal-boost quacks killed people, as did his comfort with publishing a book of “Advice to Young Men and (incidentally) to Young Women” in 1829 advising them not to vaccinate their children against small-pox. Although there, too, I do find it a little comforting that if vaccines do suddenly turn deadly, it won’t entirely wipe us out—people like Pearce provide diversity in the human crop.

My hope is that people only end up yellow-pilled because they think it’s the only way to be contrarian. They think you need to be fearless with your opinions, even a little cavalier with the truth, to ever be able to spot the many areas where conventional wisdom is wrong.

If so, I have good news! Even granting that premise, you can do significantly better by just having the teensiest more faith in humanity as a whole. People in power lie. Elites get stuff wrong. But successful secret worldwide conspiracies of millions of people probably never happen. Living in downtown Brooklyn at the start of the U.S. pandemic, my dog-walk every day took me past a hospital that was using trucks as temporary extra morgue space. Scenes like that were happening all over the world. There are bastards who would fake that stuff, but I truly believe that there are not enough of them to fake it everywhere.

And cultures have dumb food fads that do more harm than good. But not often enough to explain the universal love of the potato. Give people a little more credit than that.

Addendum: In the comments, Pearce points out that I don’t rebut Cobbett’s fuel cost argument—cooking potatoes at home could be prohibitively expensive if you lived in London and didn’t have ready access to cheap flammable stuff. I skipped over it because it looked like Cobbett stopped using it only a couple years later, but for the sake of completeness, here’s a quick rebuttal. The fuel cost argument assumes that you can buy some other source of carbs, probably baked bread, but that you can’t buy baked potatoes, or grow them and pay someone with an oven to cook them. There’s no reason to think that should be the case, and indeed it wasn’t. In fact, only a few years after Cobbett’s death (I’m glad for his sake he didn’t live to see it), the “baked-potato man” became a regular fixture on the streets of London. These were cooked in bulk at bakeries, salted and buttered, then kept hot by vendors using insulation and a charcoal fire. They were famously cheap enough that some people would buy one just for the warmth on cold days, and carry it around in gloved hands rather than eat it. According to an 1840 court case, you could get one for a halfpenny. This was obviously not the most cost-efficient way to get baked potatoes, but it still beat bread. A loaf of bread cost at least 7.5 pence, or the cost of 15 hot, buttered, salted baked potatoes. Now I’m hungry.

I really enjoyed this! Thank you for featuring my work.

You did, however, miss the most important part of Cobbett's argument, which is the cost of fuel, despite that you mention my now living in an industrialized society with easy access to food etc, which makes the difference in our access to technology profoundly important to the argument. He most of all says it is fuel costs that makes the math not work.

Further, the time spent by women boiling potatoes, as well as the quality of life difference in living off of bread compared to boiled potatoes.