Levenshtein's Festival

On the mythic roots of autocorrect.

The great rabbi Eliyahu created a golem to do his labor and protect against pogroms. He sculpted it out of clay, and gave it life by inscribing on its head the word “emet,” truth. The golem was a strong and faithful servant. But, to Eliyahu’s surprise, it kept growing. Every day it was a little bigger—perhaps it was adding more clay itself? Worried that it would destroy the world, Eliyahu tried to destroy it, but it fought back. In the struggle, Eliyahu’s face was scarred, but he succeeded in erasing the first letter in “emet” from the golem’s face. This left the word “met,” death, and straightaway the golem died. Bless Eliyahu’s memory!

— Traditional Jewish folktale

1. Met/Emet

It’s hard to celebrate something you’ve just finished destroying, but such was life in Soviet Russia.

In 1957, the Soviet Union, for the first time, offered to host the Sixth World Festival of Youth and Students, an international celebration of socialist youth culture. In Moscow, where the festival was to be held, this presented certain challenges, chief among which was that Moscow had just finished eradicating local socialist youth culture. There had been an attempted revolution in Hungary at the end of 1956, which was crushed by the Soviets. At Moscow State University, students began hijacking classes and meetings to discuss the implications: according to Communist doctrine, there should never be a need for a popular revolution in a Communist country. The students also cited Marxist-Leninist doctrine that the Party should never oppose popular movements with force. The obvious conclusion was that the people were not actually in charge. This dissenting movement joined forces with the artistically-inclined students calling for freedom of expression, and started talking about a “socialist revolution against the pseudo-socialist state.”

In response, all political science classes were shut down until the university’s branch of the Komsomol, the unofficial “youth division” of the Communist Party, could put together a list of names. 140 students were expelled, officially for “hooliganism,” and others were deported.

So while 30,000 students from around the world were planning out what to perform at the festival, creating art for it, and writing about it, the remaining students at Moscow University itself were doing their best to become invisible. This was not a good look. The Komsomol put one of their own in charge of fixing it: a 21-year-old mathematics student named Vladimir Levenshtein.

It so happened that the very second Tam approached the king’s sickbed Mazel’s year had come to an end and Shlimazel had taken his place. It was shlemazel who made Tam say “dog” instead of “lioness.” Shlimazel had indeed in one second destroyed what had taken Mazel a year to do.

- “Mazel and Shlimazel” by Isaac Bashevis Singer, based on a story his mother told him. 1967.

2. Socialise, Socialist!

Levenshtein was presumably chosen, or volunteered, because of his hobbyist interest in poetry. But it’s also possible that the Komsomol knew this was going to be a tough job so they gave it to the Jew.

People with names like Levenshtein did not have an easy time of it in Russia. It’s a minor miracle he was able to get into the university, especially its highly competitive math program. He happened to turn 18 in just the right year, 1953, when Russian anti-Semitism was at a low ebb after Stalin’s death. Stalin had been fabricating Jewish conspiracies and cracking down on Jewish organizations, so now his would-be successors were making secret speeches condemning anti-Semitism as a Stalinist plot. It would be another few years before the Party again felt it was in their best interest to demonize the Jews, at which point prospective math students with Jewish names began to be given a special in-person test nicknamed the “gas chamber,” one where there were no right answers—everything they said was declared wrong.

To the extent that there was a right answer to the festival problem, Levenshtein found it. In the official school newspaper, Levenshtein announced that the Komsomol was founding its own Creative Club, and that it would be patriotic to contribute to it. The notice closed with a bit of doggerel poetry he’d clearly written himself, which helped signal that amateurs and novices wouldn’t be sneered at. So students who hadn’t been part of the art scene before, and therefore survived the purge, felt comfortable participating.

The Club held a contest for the best Satirical Poster … satirizing, of course, only other students who didn’t work hard enough, seemed too into British culture, or were just generally annoying. Students who had never held a camera were given a crash course in photography. Similar measures were taken for dance, clothing, and song. The University’s House of Culture was soon filled with students working diligently to prepare.

The Festival was, in many respects, a success. According to a CIA analysis written the following year,

The Festivals have always been notable, and the Sixth was, as the Communists intended it to be, “the greatest ever.” As already noted, the programming and scheduling down to the last detail were a striking performance, even from the point of view of critical Westerners.

The Soviets also dodged the obvious danger from the Hungarian delegation—according to observers, basically all of the hundred-plus “Hungarian students” were Soviet spies, who told everyone that the Hungarian revolutionaries had been secret Nazis.

Still, as authoritarian regimes keep rediscovering, if you want to suppress dissent, inviting in a bunch of foreign students is a really bad idea. I think it would’ve been difficult to even acknowledge the dangers posed by the half of all delegates who hailed from outside the Soviet bloc. Surely, comrade, you’re not suggesting the American and British socialists will be noticeably richer, despite being trapped by capitalist exploitation? Or that the Polish socialists will be coming from a much freer society and be horrified at the state of Russian art and philosophy?

And then there were the Israelis. The organizers thought it would be safe to let in two separate Israeli delegations, one Communist, one Zionist. With every event precisely scheduled, they were able to ensure that an Israeli was never in the same room as a visiting Arab. So what could go wrong?

They’d neglected to consider the effect on Moscow’s Jews.

When Israelis held their first concert of the festival, people in the audience cried. Jewish culture had been essentially banned—as recently as 1955, elderly Jews were being sent to labor camps for the crime of possessing Hebrew literature. This was their music, and they hadn’t heard it played in public for a generation. The Israelis were besieged and swarmed everywhere they went. A British delegate wrote afterwards that

…groups of Jews crowded around the living quarters of the Israeli delegation although it was far out of town, at the ‘Timiriazev Academy’. It was a virtual siege and every young Israeli leaving the building was immediately surrounded by throngs of Jewish youth, with innumerable questions about Israel. The same performance repeated itself again and again in the streets of Moscow. The peak of this experience was reached when the Israeli delegation visited the Moscow Synagogue. Many of its members were asked to read the weekly portion from the Bible, and the thousands of worshippers, with tears of joy in their eyes, gave vent to their emotions and expression of happiness which overwhelmed them at the sight of these young men, who came to them from the Jewish state, and at the sound of their Hebrew as a living language.

The Festival was a turning point for Soviet Jews. Before, they’d been a convenient punching bag, condemned as “rootless cosmopolitans” or counter-revolutionary saboteurs. Now, they were an interest group. The following year, on the eve of Simchat Torah, ten thousand Jews gathered in the streets of Moscow to sing Yiddish and Hebrew songs. The militia tried, and failed, to make them stop. They were back the next year, and the next, and the next. The Festival was growing larger and larger, and its creators were helpless to stop it.

He who has not witnessed Simhat Torah in Moscow has never in his life witnessed joy!

-Elie Wiesel

3. String Staring

Vladimir Levenshtein graduated the year after organizing the Festival, and had a long and celebrated career studying some of the intersections between math and language. There doesn’t seem to be a consensus technical term for his precise field, but “stringology,” coined by Zvi Galil in 1984, comes close enough that for the purpose of this article I’m going to pretend it’s universal.

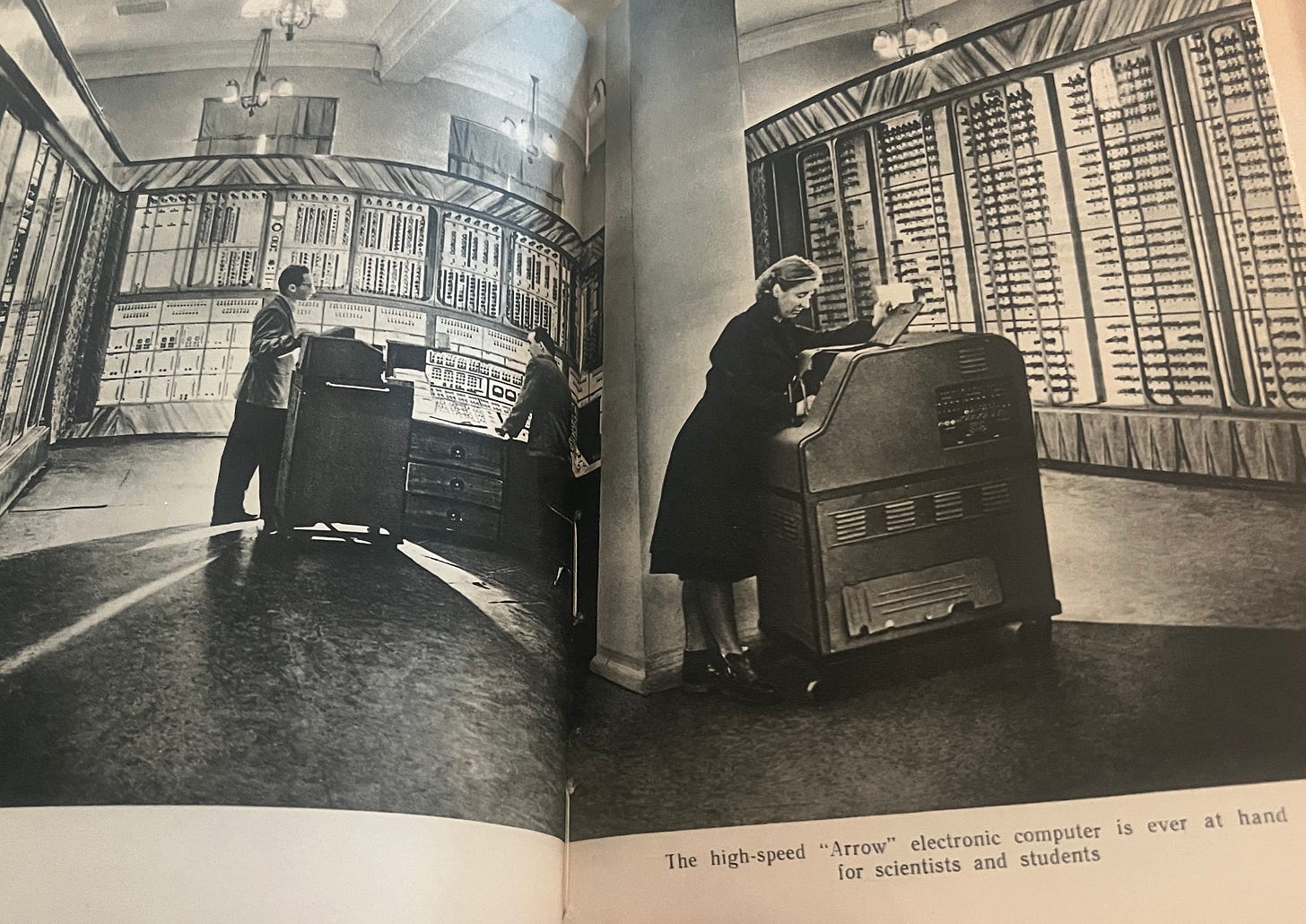

He’s best known for what today we call “Levenshtein distance,” part of a body of work that’s foundational to the practical study of typos. In the sixties, stringology was getting more attention because of the exciting possibility of computerized error correction.

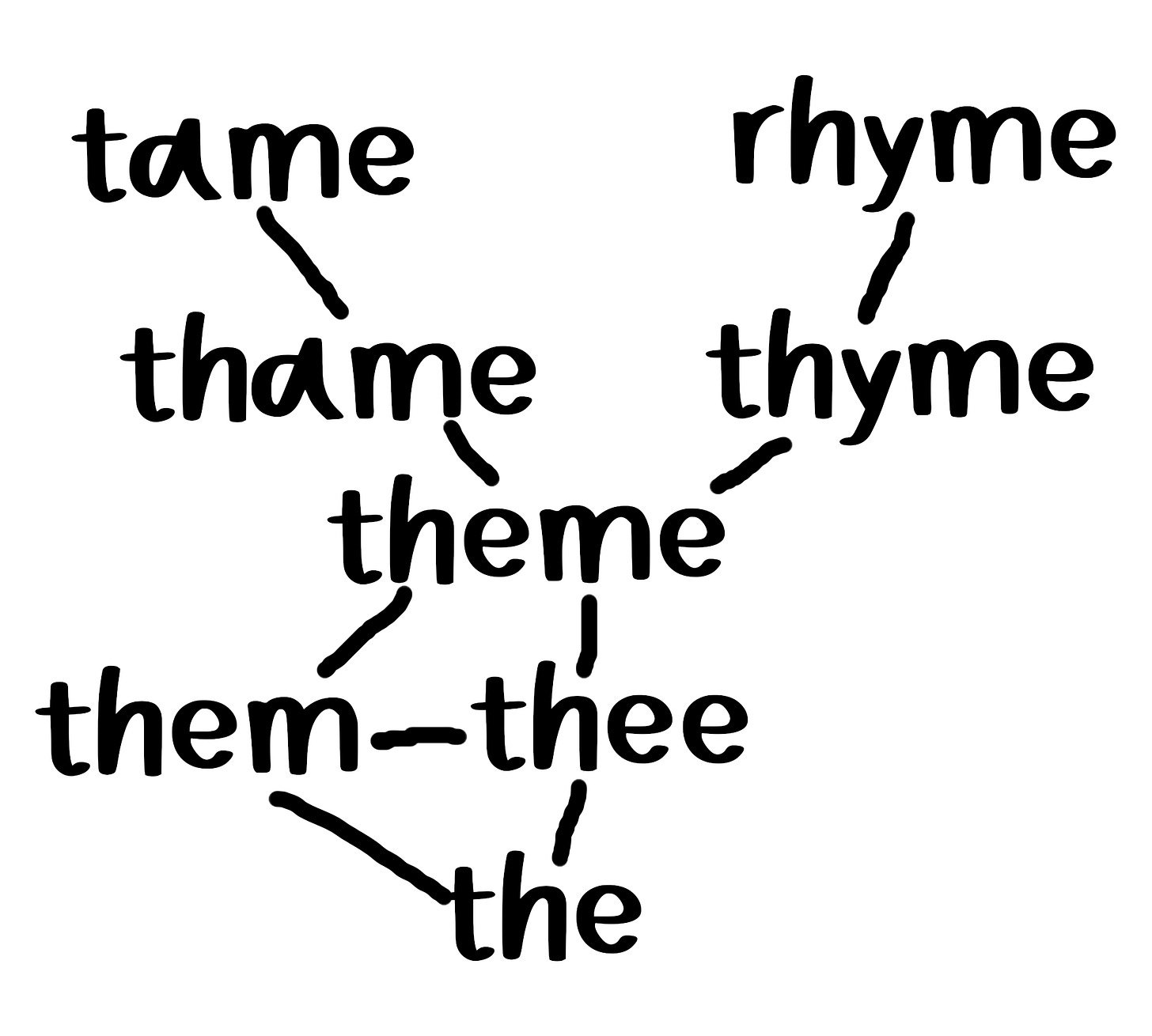

In a 1965 paper, he notes that previous work in the mathematics of error has focused on errors of substitution: replacing a 0 with a 1 in a binary code, for example. His concept of edit distance includes this kind of error, but also includes errors of deletion and addition, such as changing emet to met or vice versa.1 If you can change a word into another with one of these operations, the two words have an edit distance of 1 from each other. If it takes 2 operations, the distance is 2. For example, “theme” has a distance of 1 from “thee” because the only difference is the “m.” But it has a distance of 2 from “the” (two deletions), from “rhyme” (two substitutions), and from “tame” (one deletion and one substitution.)

Most spell-check algorithms are derived from Levenshtein distance. It’s how your autocorrect knows that “crative” is more likely to mean “creative” than “crater.” It’s also part of how we do genomics. Mutations are typos in genetic code, after all. You can map out a population in terms of how many mutations separate each of your genetic samples, and get something that corresponds pretty well to relatedness, ancestry, and geography.

In the sixties, though, Levenshtein himself wouldn’t have brought up the mutation aspect. Scientists had theorized about genetic mutations for decades, and in the West, the structure of DNA had been known since 19532. But Stalin and Khrushchev didn’t believe in genetic mutations. In the Soviet Union, it was nigh-suicidal to write about them in the early sixties, and it was career-suicidal until the reforms of the eighties. Levenshtein must have been very careful in what he said and wrote. We can infer this from the severe lack of public information about his early life, as well as the observation that he survived it.

For the same reason, I don’t know to what extent Levenshtein was inspired by the golem legend. I don’t even know to what extent he thought of himself as Jewish3. The government wouldn’t have let him forget that part of his identity—the first thing any bureaucrat would see in his file would be his Personal Record Sheet, with “Ethnicity: Jewish” on its fifth line. But that didn’t mean he had to bring it up, let alone admit that it was an influence on his work. Maybe his parents told him the story. Maybe, like many in Moscow, he only reconnected with Jewish culture after the Festival.

At the very minimum, though, Levenshtein was born into a tribe that had spent millennia talking about gematria, doing math with letters. He was shaped by it, whether or not he knew. Stringologists are often Jewish.

4. Claude’s Clauses

At a gathering of stringologists in 2003, Alberto Apostolico’s eyes lit up when he realized he was drinking wine with both Vladimir Levenshtein and Moshe Lewenstein. He asked for a picture to be taken of the three of them. Apolistico stood between Levenshtein and Lewenstein. “I am the Levenshtein Distance!” he declared.

-Traditional stringologist folktale

About 1700 years ago, a rabbi came from Israel to Babylonia. He was asked to teach some new insight about the Torah. He started out by saying: “Jacob the Patriarch did not die!”. You have to understand that there was an inherent difference in the way the Talmud was studied in Israel and the way it was studied in Babylonia. In Israel the study was more allegorical whereas the Babylonians were more technical and literal. Thus, when this famous rabbi from Israel proclaimed that Jacob the Patriarch did not die, the Babylonians immediately asked him: “It says in the Bible that Jacob was mummified, and interned - did they mummify him for nought? Did they bury him for no reason?”. So the Israeli rabbi explained to them what he meant: “As long as his descendants are alive - he is alive”.

As long as there is a string to be matched, a periodicity to be recognized, a genome to be sequenced, an LCS to be computed - Alberto is alive. As long as we meet, help our colleagues, support the junior researchers, teach the students with love and care -

Alberto is with us.

-Amihood Amir, in memory of Alberto Apostolico

In college, I majored in math and minored in creative writing—in that respect, a lot like Levenshtein. I’m attracted to the idea that Levenshtein was inspired by R. Eliyahu’s golem, that some of the algorithms that built the modern world would have been harder to invent if it weren’t for that folktale. But there’s also a strong part of me that finds it ridiculous—math is math, it says. You’re just being a chauvinist. Levenshtein was just a word to me for a long time, one of the many opaque proper nouns that pepper technical language. Isn’t that the right way to learn, practically speaking? You can’t think about Al-Khwarizmi and the Islamic Golden Age every time you read the word “algorithm.” Not if you want to learn about algorithms. You need to compress an entire culture into one person, compress the person into his name, and then compress that name, Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, into “algorithm.” My decompressing it here is pretentious, a parlor trick. It’s not like 9th-century Baghdad invented algorithms, anyway. They don’t own them.

But I think I can say, without internal self-contradiction, that culture informs where you choose to look, and therefore which universal truths you discover.

Today, the wall between math and culture, between translatable and untranslatable knowledge, is crumbling anyway. I suspect that thinking clearly about LLMs, large language models, would require me to integrate these two modes of thought better than I’ve ever been able to. We’ve managed to create golems that have superhuman levels of cultural literacy but, often, subhuman math ability, which is the only part of the current moment science fiction didn’t tend to anticipate. While Googling for other people writing about the topics in this essay, I of course had the Google AI commenting on my searches whether I wanted it to or not. It easily understood the relationship between Levenshtein distance and the golem story, but it had a lot of trouble with the idea that March 1st, 1953 was the day after February 28th, 1953. The vibes of those dates are just so different!

5. Heritage + Hermitage

The numerologist counted the bills again slowly, then pushed them into a cash drawer in his desk. He said, “Your case was very interesting. I would advise you to change your name to Sebatinsky.” “Seba— How do you spell that?” “S-e-b-a-t-i-n-s-k-y.” Zebatinsky stared indignantly. “You mean change the initial? Change the Z to an S? That's all?”

“It's enough. As long as the change is adequate, a small change is safer than a big one.”

“But how could the change affect anything?”

“How could any name?” asked the numerologist softly. “I can't say. It may, somehow, and that's all I can say. Remember, I don't guarantee results. Of course, if you do not wish to make the change, leave things as they are. But in that case I cannot refund the fee.”

- “Spell My Name With An S” by Isaac Asimov. 1958.

The iconic American science fiction writer Isaac Asimov believed, incorrectly, that he was cut off from his Jewish heritage. He said, inaccurately, that he had only ever written one Jewish story, and it’s not the one I just quoted, nor any of his stories about golems robots run amok. It’s “Unto the Fourth Generation,” published in 1959. There, a modern-day man named Sam Marten travels through a dreamscape version of New York City, searching for someone with the name Levkovich, without knowing why. The more he looks, the closer the names of the people he finds: Lefkewich, Lefkowitz, Levkowitz, Lefkowicz. Meanwhile, Marten’s great-great-grandfather, Phinehas Levkovich, is looking for him, among Martins, Martines, Mortons, Mertons.

There’s an idea attributed to I. L. Peretz that every people is a chosen people. If the world has a plan, every culture is a part of that plan; every culture that does exist should exist, not just as a meme cluster floating around in a fusion megaculture, but embodied in a people. That idea’s gradually become part of modern liberalism. It’s part of the ideology of diversity, equity, and inclusion, which is locked in perpetual struggle with the competing liberal ideology of cosmopolitanism—the melting pot.

We often try to have it both ways. Superman, like most classic superheroes, was created by the sons of Jewish immigrants. He embodies an ultimate wish-fulfillment fantasy. Clark Kent is flawlessly assimilated: he fits into human culture perfectly, thinks of the Kents as his parents, never has trouble passing. At the same time, his connection to his alien heritage makes him the most powerful person in the world. Any time he wants, he can fly to his Fortress of Solitude and learn from a hologram of his other father, the one who died on Krypton.

In Asimov’s story, Levkovich is finally able to give his blessing to his daughter’s daughter’s daughter’s son, his dying wish miraculously granted. In the original version of the story, it’s implied that Sam Marten immediately forgets all that’s happened and returns to his life just as before. When Asimov first met Janet Jeppson, his future wife, she suggested he make one small change to the story. When he reprinted it, he added this line to the end:

Yet somehow he knew that all would be well with him. Somehow, as never before, he knew…

Bonus: More Typo Demons

In writing this, I started putting together a list of folktales that have something to do with typos or other little errors. I never finished it, and I don’t think I’m going to be able to make it into a coherent article, even by my loose standards of coherence, so I’m just going to link to it here for those interested.

A common variant, Damerau-Levenshtein distance, also includes transposition errors, such as changing etch to tech by switching the order of the first two letters.

A little coincidence I noticed researching this article: On February 28th, 1953, Francis Crick, high on the discovery of the double helix, burst into a pub and announced that he had found the secret of life. One day later, Stalin, who had banned genetics research, suffered his fatal stroke.

If anybody out there does, please reach out!

So the Met Gala is a kabbalistically celebration of death? Checks out, I guess.

You give LLMs too much credit. They are improv machines, or the next likely word guessers.