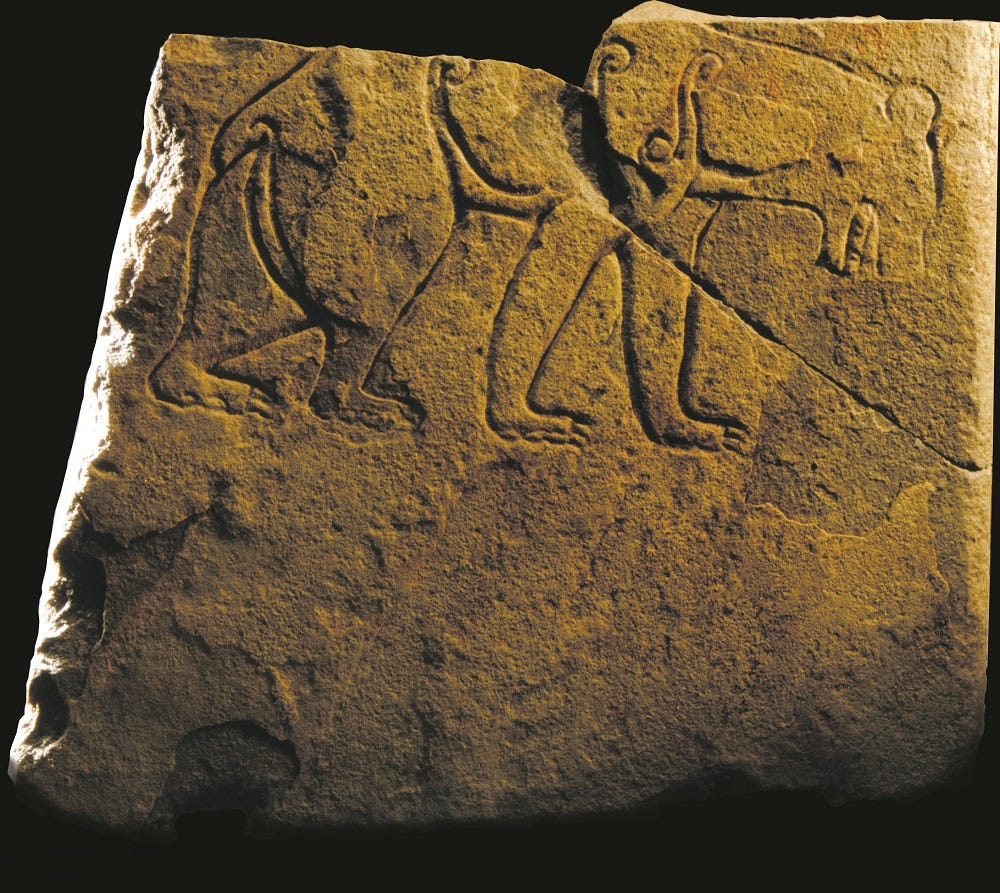

The Hermit and the Bear

A cautionary tale whose moral keeps changing.

A hermit, once, through some twist of fate, befriended a bear. The bear protected him from everything, even flies. But one day, while the hermit was taking his siesta, despite the bear’s best efforts a fly landed on the hermit’s nose. The angry bear swatted the fly, and accounts differ on whether the hermit survived the bear’s mistake.

So goes the tale, first recorded in the Panchatantra, a collection of Indian fables compiled in the fourth century. It’s probably much older than that. It’s been told in many languages, with many different morals. Or, I mean, the moral is always “don’t have a pet bear1,” but different authors generalize that sensible rule in different ways.

The oldest texts tend to give a moral along the lines of “a foolish friend is worse than a wise enemy.” Choose your friends carefully, because consorting with unworthy people is dangerous. After that, it evolves.

Rumi

Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī is perhaps the most-read poet in the world, so maybe he doesn’t need much of an introduction. His poetry, written in Persian in the 13th century, sits at the heart of mystic Islamic Sufism. In particular, his Masnavi-e Ma’navi uses the dead simple masnavi poetic form to do some very complicated things.

Rumi incorporates this story into his Masnavi, braiding it with other stories and drawing different lessons from each part. The hermit and bear are friends, in this version, because the hermit rescues the bear from a dragon. This shows that those who seek compassion will always find it. If you are in pain and danger, cry out for help, is the first moral. Then, a stranger sees the hermit and the bear and tells the hermit this is a bad idea. “I’ll help you drive it off, and be your friend in its place,” he offers. The hermit has the strength and cunning to defeat a dragon, but lacks the wisdom to hear the stranger’s words. They argue, but the hermit sees no reason to trust a stranger over someone who loves him, bear or no. The moral here is that skeptics should be skeptical of everything, including their own skepticism, or they’ll never hear the truth and believe it.

He who trusts a bear over a sage, Rumi says, is something of a bear himself.

The story ends the same way here as did it in India, with the same moral: avoid fools. The love of a fool is always the love of a bear. A fool will not keep promises because oath-keeping comes from the intellect. Rumi connects this to a story of Jesus fleeing up a mountain as though chased by a lion. A passerby recognizes him and asks him what he’s running from. “A fool,” Jesus replies. “But aren’t you the one,” the passerby says, “who heals the blind and the deaf? Aren’t you the one who can bring the dead back to life? How can you be afraid of anyone?” “I can cure blindness, deafness, and death,” Jesus says, “but I have never been able to cure foolishness, and believe me, I’ve tried.”

La Fontaine

This story came to Western Europe in 1671 via La Fontaine’s Fables. Both the bear and the human are hermits, in his version, driven mad by isolation. “It’s good to speak with people, and better to be alone,” says La Fontaine, “but both turn bad when done to excess.” The hermits meet and are so overjoyed to have company that they overlook their differences.

The bear, sadly, kills his companion when he takes his fly-catching duties too far. “Unfortunately,” says La Fontaine, “the bear’s aim was as good as its reasoning was poor.”

“It’s better to be alone than to be with fools,” says the narrator. For La Fontaine, it’s a lesson about knowing when to stop.

William Godwin and Mary Jane Clairmont

In the early 1800s, William Godwin was trying to get a publishing business off the ground, but nobody wanted to buy anything with his name attached. This was mainly because of his biography of his late wife, Mary Wollstonecraft, which had thoroughly scandalized the public—Godwin wrote of Wollstonecraft’s feminism, her child out of wedlock, and her suicide attempt without an ounce of judgment, just pure love and grief. This was Not Done.

Mary Jane was his neighbor. Like Wollstonecraft, she’d traveled the world, had children out of wedlock, and then moved to the Polygon, a London housing project, to try to reinvent herself. So it’s not entirely a coincidence that she wound up sharing a fence with a man who was famously cool with that. Still, she must have felt pretty lucky. She flirted aggressively, courted, and won him.

She also came up with a solution to Godwin’s problem: publish children’s books under a fake name. If you publish books for adults, they’ll read them, recognize your radical politics, and reject you whether or not they work out who you are. But if you publish children’s books, adults won’t read them as closely and children won’t object to a little radical propaganda. Clairmont founded and ran the M. J. Godwin & Co. publishing house, and she and her husband invented Edward Baldwin, Esquire, who wrote children’s stories in English and French (William wrote the English versions, Mary the French).

Baldwin’s Fables are artfully reconstructed. An adult familiar with Aesop and La Fontaine, casually skimming them, would see that the stories remained largely unchanged and assume the morals were too. But the morals are usually quite different; often the exact opposite. Stories about obeying the King become stories about respecting the contributions of marginalized members of society. Stories of harsh justice become stories of forgiveness.

In Baldwin’s telling, the hermit feels deep compassion toward all living things. He wouldn’t hurt a spider, feeds breadcrumbs to the birds, and when he comes across an injured bear, groaning in pain, he feeds it and nurses it back to health. The bear, in gratitude, insists on following him home. The hermit is not totally pleased with this turn of events; he would rather have a dog. But the bear can climb trees to find apples, so there are advantages.

Until one day the bear swats a fly on the hermit’s nose, and the hermit wakes up in pain. He’s angry, at first, but when he touches his bruised and blackened nose and finds the dead fly, he understands. “Go, go,” he tells the bear, “I will always do you all the good I can, but we will not live together any more.”

The moral: He that admits into his company an awkward and ill-matched favourite, will some time or other have reason to grieve, even for things that were intended in kindness.

It’s the same story, just stripped of the contempt and hostility. It’s not that the bear was unworthy of the human—they just weren’t compatible life partners. And you can still feel love for someone even if you wouldn’t want them living with you. Fools still have moral worth, which is good to remember because we’re all hopelessly foolish sometimes.

I. L. Peretz

Now let’s jump forward another hundred years, and meet Isaac Leib Peretz, Polish author and one of the founders of secular Jewish diasporic nationalism—the idea that “the Jews” can and should be a nation, with a right to self-determination, without necessarily all being religious or necessarily having their own state. In the late 19th century, Peretz published short stories in Yiddish that act as their own sort of twisted fables, with sneaky morals that are often the opposite of what you expect. They’re generally loose adaptations of existing stories, usually Jewish ones. Maybe the Hermit and the Bear were part of shtetl oral culture by this point; I’m not sure.

Peretz’s hermit has withdrawn from human company because he cannot abide evil, and there’s evil in everyone. He lives in an ancient, ruined palace he’s found by a river—he doesn’t know its story, but it’s empty, so it suits him just fine. There, he studies kabbalah, hoping to rid the world of evil by awakening its soul. The hermit believes, rightly or wrongly, that all evil is just a sleeping world tossing and turning, sometimes falling out of bed—wake it up, and all will be well.

In escaping humanity, he hasn’t escaped evil. The river sometimes has destructive floods, and the fish swimming in it eat each other. But there’s no way to get more isolated than this, so he keeps working, learning the deep secrets of kabbalistic magic. As he makes progress, the spirit of the river grows angry, knowing that the hermit considers it an enemy. It starts to sabotage his study, making just the wrong noise at just the wrong time to interrupt his meditations. The hermit doesn’t want to leave—who knows how long it would take to find another empty ruin to live in? So instead, he decides to use the magic he’s learned to move the river away from the ruin, so that he can have it all to himself.

It’s an easy spell. It works right away. But as a parting shot, the river conjures an angry bear.

The hermit is safe in his palace, but having a bear running around is even more distracting than the river was. It would be evil to kill it, the hermit reasons. It’s a living creature and it hasn’t done anything wrong, per se. It’s just inconvenient. So he decides to elevate it—to use kabbalah to make the bear a more decent creature who understands what the hermit is trying to do.

This spell is harder; the bear resists ferociously. He spends the night in fierce spiritual combat with the bear, and in the end, he wins. The bear looks at him with love in his eyes, a look that says “I will be like a dog for you. I will serve you with devotion, and I will never interrupt your meditation, even to kill a fly.”

The hermit opens the gate and lets the bear in, and the bear indeed lies down at his feet and looks up with devotion. “I believe in you,” the bear’s eyes say. “Your thoughts are holy and will redeem the world.”

But the hermit has no more holy thoughts. When he reaches for them, he just feels tired. Part of his soul has gone into the bear, and part of the bear’s soul has gone into him. He’s a different kind of creature, now. He stumbles into his bed, and the bear follows him and lies down beside him.

And here is the moral at the end: A saint that lies down with a bear cannot waken the soul of the world.

That poor bear. Transformed against its will, prostrate to a strange invader, and now filled with misplaced devotion to a cause that no longer exists. Reading this story today, it feels like a parable about colonialism, and I don’t think Peretz would mind that interpretation. I think he meant the lesson to be more general, though. Peretz was part of the same Hasidic movement that would later inspire Martin Buber to write about the evils of objectification. The hermit is trying to awaken the soul of the world, but distances himself from it in every move he makes. He cuts himself off from humans, lives in a place whose name he doesn’t know, and treats the spirit of his nameless home as a problem to be solved—an obstacle and a tool. The saint is not diminished by lying down with the bear. Rather, anyone who can lie down with a bear, anyone who was willing to make a bear become so unbearlike as to lie down with a saint, is not someone who can redeem the world.

A Bear Support Group

One day, a merchant was at a crossroads, with a cart full of fruit, when a messenger arrived, galloping on a fast horse. The messenger commanded him, in the name of the ruler of that place, to abandon his cart and ride with him back to the palace. I haven’t yet learned what happened next to the merchant, but I do know what happened to the cartful of abandoned fruit. As it lay there, ripening in the day’s heat, bears smelled something delicious and sought it out. Where the four roads they followed met, so did five bears.

You might imagine that the bears would then have fought over such a bounty, but these were kind and lonely bears, and there was enough fruit to share. As they ate, they shared their stories, and discovered they had more in common than a love of apples.

“When I was young and foolish,” said the oldest bear, “I hurt my paw trying to pick berries from a thorny bush.” She2 was Indian, and her snout looked strange to the others. “A passerby, a human, heard my moans and came to help. I wanted to repay his kindness, of course, but I didn’t understand humans well enough, and killed him. So now my debt is even greater, and I will surely be reborn as something lowlier than a bear. I’m traveling to find a good deed I am actually qualified to perform, so that in my next life I might at least be some tiny creature with fur and not an insect.”

The next to speak was Persian, and had great scars running down his back. “I got these from a dragon,” he said. “As it dragged me away, I screamed for help, and a brave and clever human distracted the dragon so I could escape. I thought that meant I was supposed to be his companion for life, like the dog who guarded the cave of the Seven Sleepers3. But I wasn’t fit for the life of a dog, and in a rage against a fly I smashed the hero’s face. In the future I will consider more carefully how I fit into the plan of the world.”

The third was French, and he4 spoke in a way the others found difficult to interpret, because neither bears nor hermits tend to be fond of irony. “You need not be so grim about these little mishaps. Sometimes we are alone, sometimes in company. Sometimes I help a gardener, sometimes I throw a rock at his head. Today I feast on miraculous fruit, tomorrow I might have to eat roadkill. Such is the life of a bear. ”

The fourth, who had been traveling with him, grumbled at this and poked him affectionately. “You shouldn’t make them think you killed that gardener,” she said. “You ought not to have hurt him, but he ought not to have let you stay in his garden, so each of you can forgive the other. I saw him more recently than you did, and his face is almost healed. He’s the one who sent me to you, actually. He told me you might be lonely.” She said all this so that the group could hear, but she refused to tell her own story, to them or to me.

They all turned expectantly to the youngest bear, who had not yet spoken. “What about you?” three said aloud, while the fourth gazed at him with gentle eyes. The young bear sighed, because he did not know where he was from, or what his story was. “I think there was a river,” he said haltingly. “But it was taken from me before I was even born, so it is difficult to remember it. I am not quite a bear—that was taken from me too. Once, I saw a fly land on a man’s nose as he slept, and I did not try to catch it, like a true bear would, because I did not want to disturb him. There is a voice in my head now that tells me that when four ask you the same question, one asks wisely, one simply, one wickedly, and one silently. But I do not think that voice is mine, nor do I think it’s the voice of the river, and anyway I do not think you are as wicked as you pretend to be,” he concluded, nodding to the French bear. “Perhaps one of you can tell me who I am?”

“We all have lives that we’ve forgotten,” said the old Indian bear, who indeed seemed quite wise. “But they’re never lost to us. We lose the story, but we remember the lesson, and so we improve. To find yourself, look at what brings you pain, what brings you joy, what spurs you to action. That’s who you are. You’ll be someone else tomorrow.”

“You are a creature of God,” said the Persian bear, trying to sound simple. “That’s what’s important. It doesn’t matter where you come from, so long as you walk towards God.”

The French bear laughed. His companion gave a slightly condescending smile. “Don’t let them fill your empty head with nonsense, little half-cub,” said the French bear. “You’re lucky not to have a past. Maybe that river would’ve told you pretty stories about reincarnation or a divine plan, but that kind of thing just makes humans and bears confused and violent. Keep it all at arm’s length, and pick only the tastiest berries from the bushes with the fewest thorns.”

The fourth bear walked over and leaned against him, which is the way bears hug when they’re being friendly. “I think it’s very nice,” she said, “that you didn’t hurt that fly.”

Bonus: Byron and Kipling’s Versions

Rudyard Kipling was Peretz’s contemporary, and would likely have been familiar with multiple versions of this story, Indian and Western. But we’re talking here about the guy who wrote about the White Man’s Burden to civilize the other races, which isn’t really compatible with either of those viewpoints, let alone Peretz’s. He never wrote a straight adaptation of the story—the closest he comes is a poem called “The Truce of the Bear,” whose moral is that even if a bear stands up on its hind legs and looks kind of human, you should still shoot it before it rips off your face.

But his Jungle Book, which takes place in India, is something of an inversion. The bear, Baloo, is a wise teacher who educates the hermit child Mowgli. Mowgli is thoroughly assimilated into the ways of jungle life—when he tries to do human things, Baloo corrects him with a cuff to the head. This is all portrayed as right and proper. Baloo’s ways are better than Mowgli’s people’s, so why shouldn’t Mowgli be made to learn them?

The classic Disney animated adaptation takes the inversion one step further. In one scene, Baloo is floating on his back down a river, with Mowgli sitting on his stomach. Baloo lazily closes his eyes, and in that unguarded moment two bad things happen—a fly lands on his nose, and monkeys kidnap Mowgli, replacing him with a monkey of similar weight so that Baloo doesn’t notice. His eyes still closed, Baloo asks Mowgli to swat the fly. The monkey hits him in the face with a stick.

Lord Byron was also a poet, but his adaptation of The Hermit and the Bear wasn’t a poem, but performance art.

Byron had a pet dog named Boatswain whom he loved dearly—Boatswain’s funerary monument is larger than Byron’s own. When he became a student at Cambridge, he was told Boatswain couldn’t come. It was against the rules. Outraged, Byron looked over these rules, and noted that they’d somehow forgotten to make a rule against bringing your pet bear to college. He used his considerable means to acquire a relatively tame bear, gave it a hat and a muzzle, and took it to Cambridge. (Supposedly, a nearsighted fellow passenger on the coach there got annoyed at the bear’s snoring and tried to wake him up, literally if unwittingly poking the bear.)

Byron seems to have kept the bear with him throughout his stay at Cambridge. His teachers were not pleased but there was, indeed, no rule against it. When asked, he explained that the bear was a prospective student.

Not always a bear. The oldest Sanskrit versions have a monkey, and some variants substitute a foolish human.

Bears are usually female in Sanskrit.

This is the analogy Rumi used. The Seven Sleepers are seven Christians who slept in a cave for about two hundred years to escape Roman persecution. They appear in Christian legend, but they’re also in the Quran, which gives them a dog, and notes that people disagree over exactly how many sleepers were in the cave and whether that count includes the dog. The moral of that part of the story is to have epistemic humility and not trust anyone who claims to know for certain.

Bears are usually male in French.