The View from the East River

Diaries of New York City tourists, 1774 - 1961

New York City is the most effective propaganda for America. For the country, for democracy, for our people. Some from the old world can sneer at our small towns, even at our other port cities. But New York City has never failed to awe.

John Adams, on first arriving in New York City for the Continental Congress, wrote in his diary that “This City will be a Subject of much Speculation to me.” After walking up “the broad Way,” he was impressed first and foremost that you could just walk along one straight street the entire length of the city. You can’t do that in Boston. The streets and houses were far more elegant and grand, too.

On the other hand…the people were so rude.

With all the Opulence and Splendor of this City, there is very little good Breeding to be found. We have been treated with an assiduous Respect. But I have not seen one real Gentleman, one well bred Man since I came to Town. At their Entertainments there is no Conversation that is agreable. There is no Modesty—No Attention to one another. They talk very loud, very fast, and alltogether. If they ask you a Question, before you can utter 3 Words of your Answer, they will break out upon you, again—and talk away.

Diary of John Adams, 1774.

Johann Conrad Dohla was a Hessian, a private in one of the many German mercenary companies hired to help put down the American revolution. New York was already conquered and occupied by the time he arrived. Dohla isn’t the best source for facts—he gets names and geography wrong, and claims to have been menaced by giant man-eating lobsters on the voyage over1. But he’s an excellent source for vibes. New Yorkers were apparently more polite than Bavarians, so he doesn’t have the same complaint as Adams. The people are so varied, rich, and free2. You can be any religion! Except Catholic. You can be any race! Except it’s a very bad idea to be Black.

New York is a large, beautiful, rich, and splendid port and trade city. It consists of about six thousand houses and very many inhabitants, because in many houses forty to fifty persons live. The houses are often four, five, or even six stories high…

…

All religions are tolerated here, and everyone can and may speak and serve God without hindrance according to his propensity, judgment, and style.The people know how to live, are without worry and content in all situations. The good living style found among the English is also found among them. They love comfort and delicacy and are very temperate in their eating and drinking, preferring tea with milk and sugar and always living in a healthful manner. All religions have churches and prayerhouses, except the Catholics. The Jews, however, are not, like ours in Europe and Germany, recognizable by their beards and their clothing, but dress similarly to other citizens, are clean shaven, and eat pork, which is forbidden by their laws. Also, Jews and Christians marry together without giving it any consideration. The females go about with curls and in French attire that among all other religions would be worn only by ladies of the upper class.

The inhabitants have many blacks, which they call blacks or Negroes. These are slaves and are bought and sold like cattle, for a lifetime or a number of years. They must tend the estates and fields of the inhabitants, and do all other work throughout the year, because the white inhabitants of America are accustomed to doing very little work, having their blacks do it for them.

The latter, however, receive nothing but uncooked food and bad clothing of rough cloth, or woolen items, and beatings with clubs or even with iron rods.

Diary of Johann Conrad Döhla, 1777.

Domestic Manners of the Americans was the book Fanny Trollope wrote for her British compatriots after her first trip to the U.S.A. It is not complimentary. Trollope is contemptuous, morally outraged, and unrelentingly negative. Except in one place. New York City was so full of, like, everything that she struggled to even describe it, let alone critique it.

But, of course, they’re not proper ladies and gentlemen there, so it’s not for her.

Sin and shame would it have been, indeed, to have closed our eyes upon the scene which soon opened before us. I have never seen the bay of Naples, I can therefore make no comparison, but my imagination is incapable of conceiving any thing of the kind more beautiful than the harbour of New York. Various and lovely are the objects which meet the eye on every side, but the naming them would only be to give a list of words, without conveying the faintest idea of the scene. I doubt if ever the pencil of Turner could do it justice, bright and glorious as it rose upon us. We seemed to enter the harbour of New York upon waves of liquid gold, and as we darted past the green isles which rise from its bosom, like guardian centinels of the fair city, the setting sun stretched his horizontal beams farther and farther at each moment, as if to point out to us some new glory in the landscape.

New York, indeed, appeared to us, even when we saw it by a soberer light, a lovely and a noble city. To us who had been so long travelling through half-cleared forests, and sojourning among an “I’m-as-good-as-you” population, it seemed, perhaps, more beautiful, more splendid, and more refined than it might have done, had we arrived there directly from London; but making every allowance for this, I must still declare that I think New York one of the finest cities I ever saw, and as much superior to every other in the Union (Philadelphia not excepted), as London to Liverpool, or Paris to Rouen. Its advantages of position are, perhaps, unequalled any where. Situated on an island, which I think it will one day cover, it rises, like Venice, from the sea, and like that fairest of cities in the days of her glory, receives into its lap tribute of all the riches of the earth.

…

I will not, therefore, attempt a detailed description of this great metropolis of the new world, but will only say that during the seven weeks we stayed there, we always found something new to see and to admire; and were it not so very far from all the old-world things which cling about the heart of an European, I should say that I never saw a city more desirable as a residence.

…

Gentlemen, in the old world sense of the term, are the same every where; and an American gentleman and his family know how to do the honours of their country to strangers of every nation, as well as any people on earth. But this class, though it decidedly exists, is a very small one, and cannot, in justice, be represented as affording a specimen of the whole.

- Domestic Manners of the Americans, by Fanny Trollope. 1832.

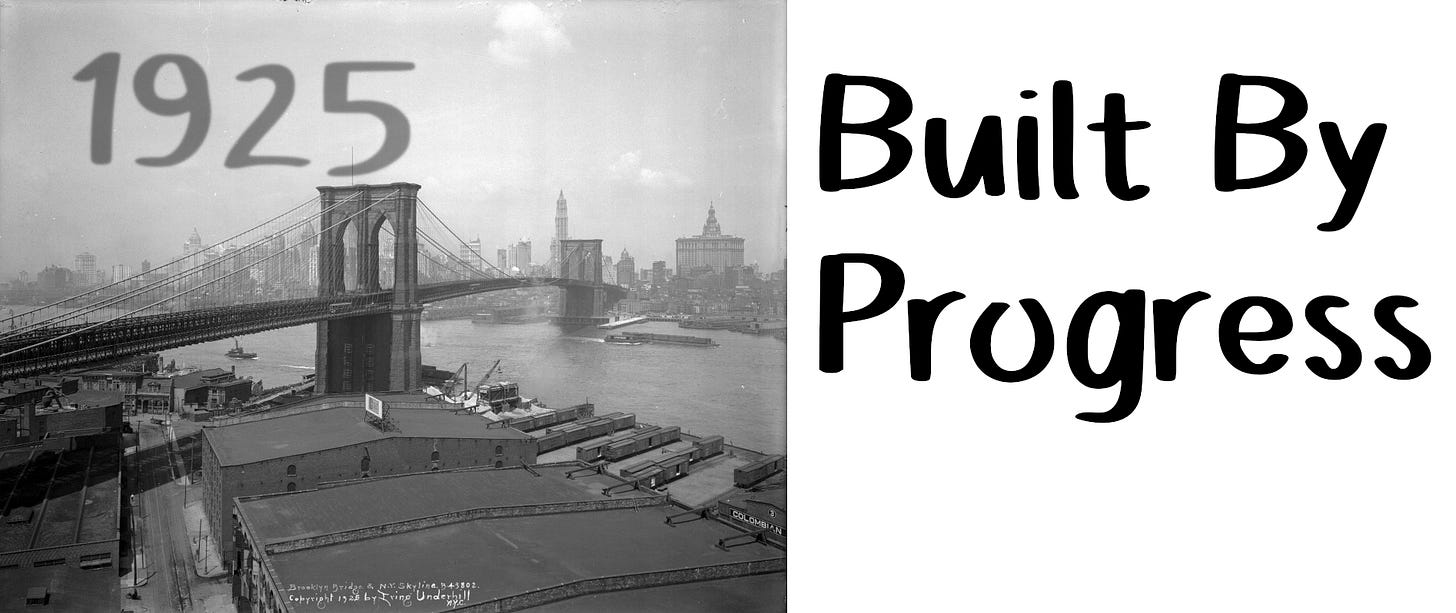

The Russian poet Vladimir Mayakovsky was a committed Marxist-Leninist, but he was also a Futurist, in love with progress of all kinds. Generally those two ideologies can mesh pretty well. But on visiting New York City, one of the most capitalistic and most futuristic places on Earth, a Communist Futurist has to pick a side. His poem, The Brooklyn Bridge, starts by acknowledging the choice he’s making.

Okay, Coolidge, about this you can be loud. Brag!

I certainly shall.

My homeland blushes as red as its flag

despite the America of it all.

As a tourist, he feels humbled. As an artist, he feels thrilled. As a futurist, he feels proud—the Brooklyn Bridge is a part of the future he’s helping to build.

I’m proud of this metal mile.

It connects my own vision to the real.

A struggle for structure, not style.

The brutal math of nuts and steel.

It’s full of inequity, he writes. It’s a symbol of Europe’s conquest of America. And if civilization ended tomorrow, you could reconstruct it all just from studying the Brooklyn Bridge.

Albert Camus was a philosopher and novelist from French Algieria, part of the existentialist movement (although he always refused that label). He survived the Nazi occupation of France, writing an underground newspaper for the French Resistance. And even given that bio, you might be surprised by just how bleak he is. Here’s his very on-brand diary entry from the day before he entered the city.

We’ll anchor in the mouth of the Hudson but won’t disembark until tomorrow morning. In the distance, Manhattan’s skyscrapers stand against a backdrop of mist. My heart is still and cold, as it is when faced with sights that don’t move me.

The next day, he tries to keep that heart chilly, but he knows it’s probably a losing battle.

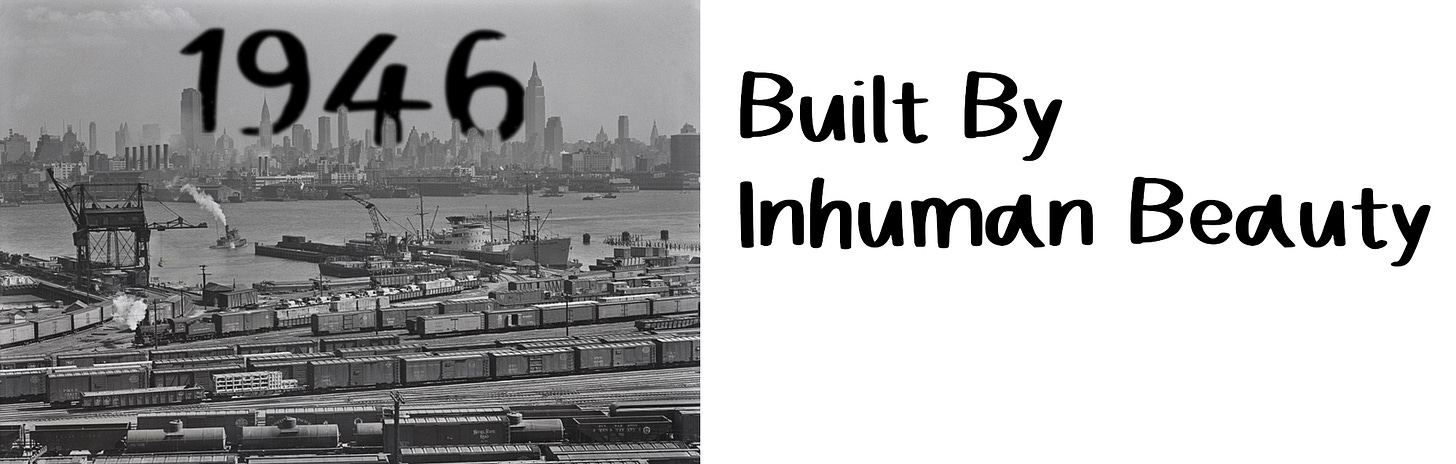

Monday. Went to bed very late last night. Got up very early. We sail through New York Harbor. A tremendous sight despite, or because of, the fog. Order, power, economic strength, they’re all here. The heart trembles before so much remarkable inhumanity.

I don’t disembark until eleven o’clock, after a long series of formalities where, out of all the passengers, I’m the one treated as suspect. The immigration officer ends up apologizing for having kept me. “I was required to do so, but I can’t tell you why.” A mystery—but after five years of occupation …

…Tired. My flu is coming back. I catch my first glimpse of New York on shaky legs. At first sight, a hideous, inhuman city. But I know people can change their mind.

…

I go to bed as sick at heart as in body but knowing perfectly well that I’ll have changed my mind in two days.

That’s Monday. By Friday, I think we kind of broke him?

Friday. Knopf. Eleven o’clock. Cream of the crop. Broadcasting. Gilson’s a nice guy. We’ll go see the Bowery together.

…

Beautiful blue sky that reminds me we’re at the same latitude as Lisbon, which is hard to imagine. In tune with the flow of traffic, the gold-lit skyscrapers turn and spin in the blue above our heads. A moment of pleasure.We go to [Fort] Tryon Park above Harlem, where we tower over the Bronx on one side and the Hudson on the other. Magnolias blooming pretty much everywhere. I try a new type of these ice cream that I enjoy so much. Another moment of pleasure.

Diary of Albert Camus, 1946.

Polish mathematician Hugo Steinhaus, whom I’ve written about before, endured an even bleaker Nazi occupation, and his “liberation” from it was by the Soviets. “The happiest day of my life,” he said once, “was the one after the Germans left and before the Soviets arrived.” He never emigrated, but you can tell from his writing about travel that he was mentally a pre-refugee, sizing up everywhere he went as a potential refuge.

Steinhaus, like Camus, was quite dark and cynical. But the view from the Brooklyn Bridge does what it does.

On September 9, 1961, we stopped over at the Rockefeller Institute in New York on our way to South Bend; I wanted to show Stefa the institute and New York. From the upper floors of the institute one can indeed get a good view of New York City, and travelling at night by car across the bridges over the East River one sees the millions of lights of Manhattan. Here it was no individual artist but ten generations of the city’s teeming millions who created the stupendous freeways and skyscrapers, the multicolored lights reflected in the river, and the gigantic bridges which amaze by the impression they give of lightness combined with a sense of the weight of the iron of which they are made. A million architects, engineers, painters, and craftsmen built the city. Each made his contribution according to an imperative of practical necessity, yet the overall effect far transcends their individual imaginative efforts. Manhattan’s base of solid rock bears the world’s capital city, and no other city comes near to wresting this title from her. The European visitor senses Americans’ pride in the achievement, and he himself is filled with optimism when he reflects that New York was built by immigrants.

Diary of Hugo Steinhaus, 1961.

New York City is still growing in population today, still powered mainly by immigration. One New Yorker in three was born outside the United States. Half of the new births here are to immigrant parents. And while we have more rivals than we did in 1961, we are still a capital of the world.

Why is New York City so rich? We stay rich because of all the ambitious and/or desperate people who come here, drawn by our wealth. But how did the snowball get rolling in the first place?

There’s an easy, simplistic answer where it’s an accident of geography. New York is a deep-water port on the East Coast. It “receives into its lap tribute of all the riches of the earth” because we’re a convenient place for a large cargo ship to dock. But it’s not just that. Philadelphia was a larger port than NYC for a long while, until the Erie Canal in the 19th century. Savannah, Georgia is a deep-water port on the same coast, and there are others too. None of them can hold a candle to Times Square.

It wasn’t just geography, and it wasn’t just exploitation—New York will grind you up to make its bread, but if exploitation were the answer then, again, why not Savannah, a city much more built by slavery than New York was?

I think, at its base, New York is built on bad manners. Most places have an idea of the culture they’re striving to create, or to maintain. They have a sense of a social upper class—good, wise people, easily identifiable by their natural courtesy. To New Yorkers, a social upper class is just the annoying rind you sometimes get at the surface of the cheese. The other day, I sat down in a subway car in Queens and started reading, until a guy with a heavy Greek accent shouted at me from the platform that the train on the other side was going to leave first. That’s New York courtesy.

If we have an old-world-style gentry here, they’re a tiny demographic. They’re not normative. Which means anybody can be not just a New Yorker, but a great one. We’re far from equal in opportunity, but there’s no ceiling on anybody’s ambition. And so, the city rises with her people.

I’m not saying anything particularly original here, and that’s kind of the point. This has been New York from the beginning, plain for all to see. Since 1903, we’ve even had a sign out in front explaining it.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.”

I’m pretty sure he’s making them up, but not absolutely positive. There’s a smattering of other stories about giant lobster attacks. I don’t think we know what their maximum size is.

“Varied, rich and free” is stolen from Judy Chicago. I feel a little guilty for appropriating her words in praise of my city when she named herself after another. But hey, her most famous work is in Brooklyn.