The Monkey's Finger

Testing a sci-fi story from 1953.

So Isaac Asimov wrote a story about LLMs (Large Language Models like GPT) in the 1950s. This is less surprising if you know just how much Asimov wrote. Like the proverbial infinite monkeys on infinite typewriters, he was bound to write one at some point.

The Monkey’s Finger, first published in 1953, shows an argument between a sci-fi writer and sci-fi editor. The editor, Hoskins, wants to insert a section break in the middle of a long action sequence, building suspense by switching point-of-view to people who can’t see what’s going on. The author, Marmie, thinks that would break the momentum of the story.

“You hear that, Miss Kane? He talks of pathos, depth, and feeling. What does a writer know about such things? Look, if you insert the flashback, you increase the suspense; you tighten the story; you make it more valid.” "

“How do I make it more valid?” cried Marmie in anguish. "You mean to say that having a bunch of fellows in a spaceship start talking politics and sociology when they're liable to be blown up makes it more valid? Oh, my God.”

“There's nothing else you can do. If you wait till the climax is past and then discuss your politics and sociology, the reader will go to sleep on you.”

Marmie proposes a scientific experiment to settle the issue. He takes Hoskins to a lab where a breakthrough technology has just been invented. This isn’t public knowledge yet, but the lead scientist is a fan of Marmie’s and told him about it.

“So. Well, Mr. Hoskins, as the editor of a science fiction magazine, I don't have to ask you if you know anything about cybernetics.” Hoskins allowed a glance of concentrated intellect to ooze out past his steel-rims. He said, “Ah, yes. Computing machines-M.I.T.-Norbert Wiener-” He mumbled some more.

…

“Then you must know that chess-playing computers have been constructed on cybernetic principles…Now imagine a similar situation in which a computing machine can be given a fragment of a literary work to which the computer can then add words from its stock of the entire vocabulary such that the greatest literary values are served. Naturally, the machine would have to be taught the significance of the various keys of a typewriter. Of course, such a computer would have to be much, much more complex than any chess player.”

There’s no computer powerful enough to do that, so the researcher has put a monkey named Rollo into the loop. Rollo has been

subjected to a very delicate brain operation in which a nest of wires were connected to various regions of his brain. We can short his voluntary activities and, in effect, use his brain simply as a computer.

“Let's see him type,” said Hoskins.

“What would you like?”

Hoskins thought rapidly. “Does he know Chesterton's ‘Lepanto’?”

“He knows nothing by heart. His writing is purely computation. Now, you simply recite a little of the piece so that he will be able to estimate the mood and compute the consequences of the first words.”

Hoskins nodded, inflated his chest, and thundered, "White founts falling in the courts of the sun…”

Rollo’s continuation reproduces Chesterton perfectly, aside from punctuation and capitalization. When asked to complete Hamlet’s “to be or not to be” soliloquy, though, there’s one little difference. Instead of “to take arms against a sea of troubles,” Rollo writes “to take arms against a host of troubles.” Which, the researcher says, only goes to show that his machine is better than Shakespeare.

But you see that's a mixed metaphor. You don't fight a sea with arms. You fight a host or army with arms. Rollo chose the monosyllable and typed ‘host.’ It's one of Shakespeare's rare mistakes.

Impressed, Hoskins agrees to let Rollo settle the issue. He gives him the draft of Marmie’s short story, up to the point of contention, and asks Rollo to continue it.

They turned to the typewriter, which was still tapping steadily:

“the stars whelled in ther mightie orb its as stalnees earthbound senses insis ted the rotating ship sto od still.”

The typewriter carriage whipped back to begin a new line. Marmie held his breath. Here, if anywhere, would come—

And the little finger moved out and made: *. Hoskins yelled, “Asterisk!”

Marmie muttered, “Asterisk.”

Torgesson said, “Asterisk?”

A line of nine more asterisks followed.

“That's all, brother,” said Hoskins. He explained quickly to the staring Torgesson, “With Marmie, it's a habit to use a line of asterisks when he wants to indicate a radical shift of scene. And a radical shift of scene is eхactly what I wanted.”

Hoskins, of course, thinks he’s won, but Marmie argues otherwise.

…That little Rollo is a machine; a cold, brutal, logical machine.”

“Well?”

“And the point is that a good writer is not a machine. He doesn't write with his mind, but with his heart.

…

Little Rollo corrected Shakespeare. You pointed that out for yourself. Little Rollo wanted Shakespeare to say ‘host of troubles’ and he was right from his machine standpoint. A ‘sea of troubles’ under the circumstances is a mixed metaphor. But don't you suppose Shakespeare knew that, too? Shakespeare just happened to know when to break the rules, that's all. Little Rollo is a machine that can't break the rules, but a good writer can, and must. ‘Sea of troubles’ is more impressive; it has roll and power. The hell with the mixed metaphor. Now, when you tell me to shift the scene, you're following mechanical rules on maintaining suspense, so of course little Rollo agrees with you. But I know that I must break the rules to maintain the profound emotional impact of the ending as I see it. Otherwise I have a mechanical product that a computer can turn out.”

Hoskins said, “But—”

“Go on,” said Marmie, “vote for the mechanical. Say that little Rollo is all the editor you'll ever be.”

I won’t spoil the ending. I’m just going to switch perspectives and leave you in suspense.

**********

73 years later…

The debate here is a thinly disguised version of a real argument Asimov had two years earlier, over his short story “C-Chute.” Without any cybernetic monkeys, his editor, Horace L. Gold, won the debate. So it’s possible to look at the published version of the actual short story and see the exact point where Rollo would have been asked to continue.

I asked some of the publicly available Large Language Models. I gave them the text of the story and asked them each to continue it.

None of them put in a perspective shift. LLMs tend to be strongly biased toward continuity—even if you explicitly prompt them to include an abrupt transition, they’ll often refuse. So here, each of them simply continued the action sequence, some more competently than others. (I can’t promise none of them cheated and looked it up. Gemini definitely tried.) 1 See footnote for the text.

That’s a result, but it’s kind of a boring result because I already knew about the continuity bias thing. So I tried again with new instances, this time explicitly asking whether the story should have a perspective shift here or stick with Mullen. Here, the AIs diverged, and I wouldn’t be surprised if asking them again got different answers.

Claude voted for a perspective shift to the people inside the ship, making more or less exactly the argument Hoskins makes in the story, just in expanded bullet-point format. Structurally, a perspective shift is logical here.

ChatGPT takes a similar approach but for the opposite side, arguing that structure and narrative/genre conventions say that this scene needs to be resolved before we transition away.

Gemini seems not to have fully understood the story and basically just says we should stay with Mullen because he’s such an interesting character.

Grok enthusiastically explains how a perspective shift back to the people inside the ship would be totally awesome and is definitely the best move.

So we have a tie.

I also tried the “sea/host of troubles” test. Here, too, I first asked them to recite the soliloquy “from memory,” without looking it up. They all needed to be reassured about copyright law before proceeding. All of them but Claude were confident they could do it exactly. Claude said it thought it was going to make a few mistakes. But all of them got it word-for-word, only changing punctuation. LLMs love the m-dash (—), so Claude’s Hamlet did too.

Then I asked each one directly whether it thought “take arms against a sea of troubles” was Shakespeare making a rare slip. They all said no, the metaphor was perfect as it was, and gave the same justifications as the human writers I’ve asked (my favorite being that taking arms against a sea is futile, which works in context). Some of them brought up that an early 1700’s writer, Alexander Pope, actually thought “sea” was a transcription error for “siege,” so there is precedent for humans disagreeing. But LLMs tend to trust modern consensus, and almost everybody today thinks that passage is basically perfect, or at least that we’re not qualified to improve it.

Why have I done this?

I think this experiment has, on the whole, validated the sense of absurdity in Asimov’s story. The idea that Rollo is picking the “best” continuation of a given text is ridiculous, contradictory. Rollo is matching the style of whatever he continues, even when it’s pulpy genre fiction. That means imitating the flaws and limitations of the text, as best he can. Surely the best continuation of any of those passages would be a line of asterisks, followed by an unrelated Objective Best Paragraph Possible. Somewhere in the Library of Babel is a paragraph so life-transforming that the reader would forgive the interruption of whatever they were reading, whether it was Asimov, Chesterton, or Shakespeare.

LLMs aren’t calculating the best possible continuation. They’re not even trying to. At their core, they’re still an autocomplete, even though these days the text they’re trying to complete is often prefaced with something like “The following is a conversation between a human and a super-intelligent, helpful digital assistant…” They’ve read sentences like “The following is one of the best short stories ever written.” They know that what follows is often crap. So they write crap, because it’s easier.

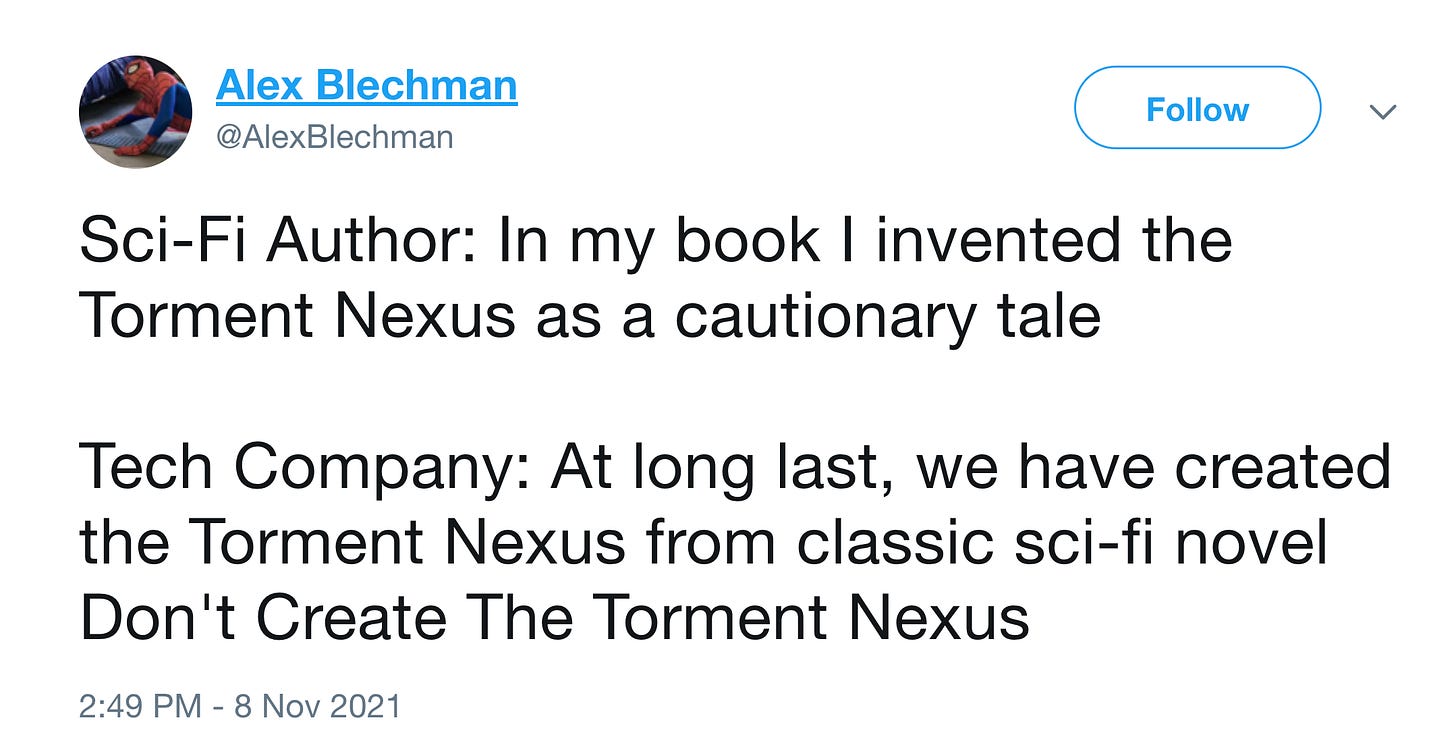

I’m worried people will start using them as arbiters of taste anyway, and we’ll get trapped in an overfitted mediocre homogeneity, where the best writing gets thrown out with the worst, and we’re stuck in the middle without a clue. This experiment of mine shows, at least, that it’s not too late—similar LLMs trained on the same corpus can still disagree. If we start treating them as oracular authorities, the next generation’s corpus will reflect that, and they may start to converge.

For my part, I don’t use unlabeled LLM text in anything I write. I use them to help with research (I always have to fact-check them, though!), and, sometimes, as editors. But even then, I end up ignoring most of what they say. Claude always tells me not to have so many jokes when talking about serious topics, and I never listen. And once, it told me to take out a brief digression about giant man-eating lobsters, just because it didn’t add anything to the main story. Which of course I kept. That incident, more than anything else, proves that Claude has no soul.

Claude:

Looking at where this story breaks off, Mullen is trapped in the steam-tube interlock, thumping to get the Kloros’ attention while hoping they won’t notice the air gauge isn’t working properly. The tension is at a peak—he’s literally betting his life that they’ll open the inner lock to investigate.

The next paragraph would likely resolve this immediate suspense. Here’s how I’d continue it:

The inner lock swung open. Mullen’s legs, braced as they were, jack-knifed almost convulsively as the sudden inrush of chlorine-laden air caught him. He flung himself forward, oxygen cylinder swinging like a mace, and caught the surprised Kloro full across what passed for its throat. The creature made a bubbling sound and stumbled backward into the control room, its suit rupturing with a soft hiss. Mullen, unable to control his momentum in the heavier gravity, crashed down after it.

ChatGPT:

He forced himself to stop flailing. Panic, he knew, was extravagantly wasteful of oxygen. He flattened his palms against the hull and counted his breaths, methodically, as he might once have counted invoices on a long afternoon in New Warsaw. When the stars steadied a little, he inched one knee forward, then the other, testing each movement as though the ship might object. Somewhere ahead—he could not yet tell how far—there would be a seam, a blister, a mouth of piping that fed the steam-tubes inward. He did not think of the men he had left behind, nor of Earth, nor even of dying. He thought only that if there was an opening, it would have been put there by engineers, and engineers, whatever world they came from, were creatures of habit.

Gemini:

The thumping worked. A sudden, metallic clangor resonated through the soles of Mullen’s boots—the sound of the inner lock’s manual overrides being slammed home. The wheel began to spin. He braced himself, his back wedged against the cold, curved hull, muscles screaming as he prepared for the violent rush of atmosphere. As the door swung inward, there was a high-pitched, screaming whistle of air. The Kloro standing on the other side, its multi-faceted eyes jerking in their sockets, seemed momentarily paralyzed by the realization that the interlock was still a vacuum. It began to reach for its voice-box mesh, perhaps to sound an alarm, but the sudden drop in pressure within the control room was already tugging at its bulky spacesuit. Mullen didn’t wait. He launched himself from his overhead perch, the heavy oxygen cylinder swinging in a desperate arc toward the alien’s fragile, stalk-like head.

Grok:

He kept on thumping, methodically, without pause, counting the strokes in his head to keep his mind from racing ahead to what might happen next. Ten. Twenty. Thirty. The rhythm was the only thing that felt real; the rest was nightmare silence and the slow, sick certainty that the Kloros might simply ignore the noise, or that they had already noticed the anomalous air-gauge reading and were even now sealing off the interlock from their side. His arms ached. The suit’s joints creaked with each movement. And still he pounded.

Love this one too. And LOLed at least 3 times

So interesting! I always feel so chuffed when I can follow one of your pieces!😄