Why We Care

On JD Vance's argument that nation-states are inherently genocidal.

I’ve recently come across three public figures, each separately arguing for the same thesis: that the coupling of a nation to a state is an inherently violent ideology. Daniel Boyarin, academic and rabbinic Jew, Mahmood Mamdani, political anthropologist and father of the frontrunner in the New York City mayoral race, and JD Vance, Vance Refrigeration.

I’ve written about Boyarin before (1, 2) and Mamdani recently, so it’s Vance’s turn. He actually makes a pretty similar argument to the other two except for the part where he endorses said violence.

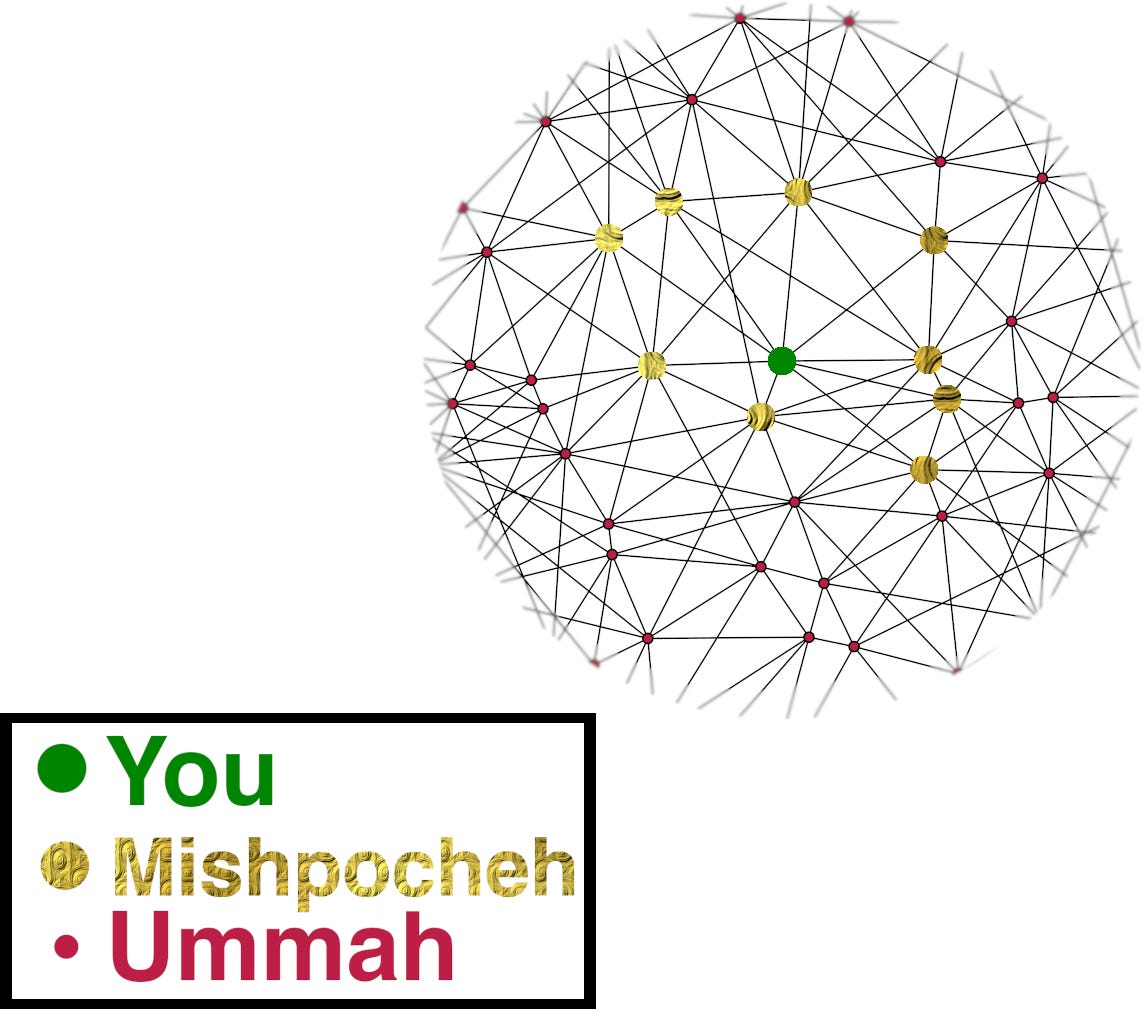

First, a refresher on definitions. A state, as I’m using the term here, is a legal entity that has sovereign privileges over its land and citizens. A nation is a group of people who recognize a shared bond—an identity. Israel is the Jewish state, while the Jewish nation includes me and excludes Palestinians. Everyone is part of more than one nation, in this sense. Political citizenship can define a nation, but so can ethnicity, creed, or voluntary association, and those are often more salient. Boyarin and Mamdani often use the Arabic word ummah to refer to this sense of nation.

A “nation-state,” then, is a setup where the two are kept in lockstep—we have a nation in mind, and we ensure that full state citizenship extends to all those, and only those, who belong to said nation. Anyone subject to the laws of the state, but not part of the nation, is at best a resident alien and at worst an invader.

That’s where the violence comes in. To achieve, or even work towards, this setup, you need to identify the foreigners on your soil and do something about them. Deport them, relocate them to a reservation, create a lower tier of rights for them, or forcibly assimilate them into your nation. Or murder them, of course. Traditionally, one murders them. But all of these solutions are coercive and beget more violence.

One of the central questions of our era, then, is whether and when the violence is justified. Do we need a nation with a strong bond in order to have a well-functioning state? Does a particular nation have a right to establish its particular state? When is coercion morally acceptable?

Vance bites the bullet. In a recent speech at the Claremont Institute, Vance argues persuasively against the idea that a nation-state can emerge from shared principles alone.

If you think about it, identifying America just with agreeing with the principles, let’s say, of the Declaration of Independence, that’s a definition that is way over-inclusive and under-inclusive at the same time. What do I mean by that? Well, first of all, it would include hundreds of millions, maybe billions of foreign citizens who agree with the principles of the Declaration of Independence. Must we admit all of them tomorrow? If you follow that logic of America as a purely creedal nation, America purely as an idea, that is where it would lead you. But at the same time, that answer would also reject a lot of people that the ADL would label as domestic extremists. Even those very Americans had their ancestors fight in the Revolutionary War and the Civil War.

We like, in America, to talk as though we share a common creed, the American civil religion in which the Declaration of Independence is scripture and voting a sacrament. But that has the same consequence as any other theory of nationhood—it implies some people here aren’t Real Americans. Are you a Real American, Vance asks, if you’re one of those “promoting alternative national anthems?” Or what about if you’re not a purely orthodox liberal, he asks. What if you disagree with some of the ideas of Thomas Jefferson expressed in that Declaration? Should that affect your citizenship?

Vance doesn’t pretend to have a fully coherent definition in mind for the American nation. He just has a few ingredients that he’s pretty sure we need, among others. Nation membership must be considered identical with state membership, he says: being an American requires sovereignty, putting other Americans above foreigners, and denying at least some legal privileges to foreigners on U.S. soil—how can it be an American right if we’re okay granting it to non-Americans? But none of those really help with the basic problem of definition. That’s why he names two more ingredients. One is participation in shared goals. The Apollo Program was “a national project in the truest sense of the phrase.” The other is a sense of America as a (very complicated) ethnicity:

Lastly, I’d say citizenship must mean recognizing the unique relationship, but also the obligations, that we all share with our fellow Americans. You cannot swap 10 million people from anywhere else in the world and expect for America to remain unchanged. In the same way you can’t export the Constitution, the written words on a piece of paper, to some random country and expect the same kind of government to take hold. That’s not something to lament or be sad about, it’s something to take pride in. That this is a distinctive moment in time with a distinctive place and a distinctive people.

And I think it’s impossible to feel a sense of obligation to something without having gratitude for it. We should demand that our people, whether first or tenth generation Americans, have gratitude for this country.

I believe, and my own story is a testament to that, that yes, immigration can enrich the United States of America. My lovely wife is the daughter of immigrants to this country, and I am certainly better off, and I believe our whole country is better off for it. But we should expect everyone in our country, whether their ancestors were here before the Revolutionary War, or whether they arrived on our shores just a few short months ago, to feel a sense of gratitude.

But even this wholesome and inclusive definition, Vance says, leaves people out, so those people (“illegal aliens who don’t have the right to be here”) have to go, and be kept out.

Now, part of the solution, I think the most important part of the solution, is you first got to stop the bleeding. And that’s why President Trump’s immigration policies are, I believe, the most important part of the successful first six months in the Oval Office. Social bonds form among people who have something in common. They share the same neighborhood. They share the same church. They send their kids to the same school. And what we’re doing is recognizing that if you stop importing millions of foreigners into the country, you allow that social cohesion to form naturally. It’s hard to become neighbors with your fellow citizens when your own government keeps on importing new neighbors every single year at a record number.

It’s all well and good to say you’re going to be a melting pot, per this school of thought. But sometimes you’re going to get a lot of immigration at once, too much for the majority to quickly assimilate, and then you’re right back to having foreigners in the country, who don’t belong because they don’t have preexisting bonds. Sometimes, too, immigrants will stubbornly insist on remaining foreign, in any or all of the other senses Vance lists. In each case, something must be done about them.

And therefore, say Boyarin and Mamdani, we should stop trying to have these tightly-coupled nation-states. Nations, sure. States, sure. But we should find ways of relating to each other, caring for each other, and working together that do not require violence. Vance, though, as a condition of his employment, draws a different conclusion. The American nation-state is valuable, and worth defending, even if it means spilling blood.

I’m not sure whether I agree with the core Boyarin/Mamdani/Vance argument (maybe we could decouple states from other things, like land, instead?) but I’ll leave that for another post or twelve. Here, I’d like to talk about three areas where I think Vance, in particular, is being incoherent: his definition of coercion, his definition of gratitude, and his definition of community.

Coercion

Of the parts of Vance’s speech that I’ve quoted so far, one bit in particular sticks out for me: the part where he talks about the government “importing” millions of people. Outside of slave trafficking, people who travel here are not commodities being bought and sold, and the primary reason they’re here is that they chose to be here. And part of the reason people choose to be here is that they expect others, already here, to be glad they came; family, friends, and employers.

Vance and his ilk talk this way because they want to frame (most) immigration as state violence. The government is bringing people in, en masse, destroying communities against their will, and exploiting the immigrants themselves (he calls them “serfs” at one point). We need to fight back. That’s a more palatable framing, to most versions of the American creed, than “we need the government to have and exert more power.”

The government isn’t bringing people in. It’s letting people in.

Towns that don’t want to grow too quickly can, and do, achieve that on their own by restricting new development. If you can ban new development and still get an overwhelming influx of new people, your community was already dying—why else would there be space? In a country where the federal government often stepped in and overrode local development restrictions, I’d have much more sympathy to the coercive-immigration framework.

I prefer, here, the common-sense approach to figuring out what is and isn’t coercion. What is physically happening, at the community level, is that the federal government is sending armed agents into places that don’t want them there, and removing people against the wishes of most of their neighbors. Our government could always tell ICE to stay out of sanctuary cities, and focus their enforcement on where it’s actually wanted. Instead, they’re raiding Little League practice in Harlem.

Gratitude

Vance, ironically, goes right from echoing Mahmood Mamdani’s political philosophy to attacking his son. (Ellipses below are in the original transcript).

Today is July 5th, 2025, which means, as all of you know, that yesterday we celebrated the 249th anniversary of the birth of our nation. Now the person who wishes to lead our largest city had, according to multiple media reports, never once publicly mentioned America’s Independence Day in earnest. But when he did so this year, this is what he said, and this is an actual quote.

“America is beautiful, contradictory, unfinished. I am proud of our country even as we constantly strive to make it better.”

There is no gratitude in those words. No sense of owing something to this land and the people who turned its wilderness into the…

Zoran Mamdani’s father fled Uganda when the tyrant Idi Amin decided to ethnically cleanse his nation’s Indian population. Mamdani’s family fled violent racial hatred only for him to come to this country, a country built by people he never knew, overflowing with generosity to his family, offering a haven from the kind of violent ethnic conflict that is commonplace in world history, but it is not commonplace here, and he dares on our 249th anniversary to congratulate it by paying homage to its incompleteness and to its, as he calls it, contradiction.

I wonder, has he ever read the letters from boy soldiers in the Union Army to parents and sweethearts that they’d never see again? Has he ever visited the gravesite of a loved one who gave their life to build the kind of society where his family can escape racial theft and racial violence? Has he ever looked in the mirror and recognized that he might not be alive were it not for the generosity of a country he dares to insult on its most sacred day? Who the hell does he think that he is?

There’s a limit to how much good faith I’m willing to assume from Vance when he’s failing to assume it of others. As a politician, he must understand that having any political vision means seeing America as both valuable and improvable. He says as much in the same speech:

Every Western society, as I stand here today, has significant demographic and cultural problems.

I know the Claremont Institute is dedicated to the founding vision of the United States of America. It’s a beautiful and wonderful founding vision, but it’s not enough by itself.

So I believe one of the most pressing problems for us to face as statesmen is to redefine the meaning of American citizenship in the 21st century. I think we’ve got to do a better job at articulating exactly what that means. And I won’t pretend that I have a comprehensive answer for you, because I don’t.

Citizenship should mean feeling pride in our heritage, of course, but it should also mean understanding milestones like the moon landings, not only as the products of the past national greatness, but as achievements we should surpass by aligning the goals and ambitions of Americans at all levels of society.

I think that we should care about all the people in our country, particularly those down-to-the-mobile, college-educated people who feel like the American dream is not quite all it’s cracked up to be.

America has serious problems, Vance says in these excerpts. Its founding vision is incomplete, and the next iterations of it are complex and murky. But all of us should strive for greater and greater achievements for the sake of all of us. If you were to try to compress all these sentiments into a tweet, you might end up with something like this:

To make Vance, himself, seem less contradictory here, we have to read a little between the lines to something he never quite says: he must believe that Mamdani is obligated to show more gratitude than Vance. Vance is allowed to be more critical—Mamdani hasn’t earned, nor inherited, that right.

Vance doesn’t quite say this out loud, because the right to criticize the government is a necessary part of citizenship, and denying it to Mamdani means denying full citizenship to him, and to everyone else who came here as a child. But he basically does say it—Mamdani has never “visited the gravesite of a loved one who gave their life to build the kind of society where his family can escape racial theft and racial violence.” That’s not, in the sense he means it, a test most immigrants have the ability to pass.1

Vance should show more gratitude toward Mamdani’s family. His father willingly put his life in danger and was beaten by police in order to build a less racist society. Taxes on his mother’s 2001 movie Monsoon Wedding paid for Vance’s education2. New York City took the brunt, also in 2001, of a blow aimed at the entire country. Muslims, like Mamdani’s family, with the courage to stay here afterwards are part of how we healed, how we didn’t get trapped in a cycle of violence. Vance thinks immigrants are disconnected from the work that built and builds our country. He’s wrong.

Community

Vance really doesn’t seem to understand community. He wonders why New Yorkers would pretend to care about atrocities abroad, why we’ve been talking about holding the heads of Israel and India to account for them, as though it were any of our business. He’s since softened his stance on this a fraction after seeing footage of Gaza. Pictures help make it real to people not directly connected. But in port cities, we are connected. I have first cousins in Israel. Zohran’s parents were born in India. I doubt many people in the city are more than a degree removed from one of our million Jews, nor from one of our million Muslims, nor from one of our close-to-a-million Desis.3

Here’s what community means to me.

Somebody calls you out of nowhere, begging for your urgent help. You drop everything and rush to their side. How many people are close enough to you that this could happen—that they might call, and you would come? Those, in Yiddish, are your mishpocheh: your family, your friends who are like family, and the people to whom you have a duty of care.

Your mishpocheh have mishpocheh, and it’s rarely the exact same group. If you showed up to your brother’s house, and the emergency turned out to be his wife’s sister’s friend’s, would you turn around? No, you care about your brother, and that means caring about the people he cares about.

So beyond your immediate mishpocheh, there’s a whole crowd of people who are part of your community. In a small town, you might be confident that anyone you met was part of that group—you may not know them, but you must know somebody who does, or somebody who knows somebody who does. In the wider world, you might have a different kind of bond, a bond of creed, that grants you the same confidence. People like that, the strangers you recognize as your own, are your ummah. Your nation. If we’re to survive, that’s what we need to be. A nation of neighbors. An ummah built of mishpocheh.

Dear Mr. Vance

JD, if you really believe in, really want, that vision of national unity you speak of, you need to understand and honor all of our national bonds. You need to see that the happiness and welfare of your native-born fellow citizens are inextricably tied to the happiness and welfare of immigrants and foreigners, and so your obligation to the one includes an obligation to the other. You need to recognize and honor the bonds created by American ideals, not just the ones created by American soil. You need to feel gratitude, not only for our country, but also for its people. Not just for the sacrifices of the dead, but also for the strength and kindness of the living.

And I think you can become that person. Heck, it would hardly be the first time you’ve transformed yourself. Not saying you necessarily will, but you might. I was writing this article when the news broke in the U.S. about the starvation in Gaza. I stopped writing it, to go look for what I was pretty sure I would find—you expressing horror, compassion, outrage, a desire to help. And of course I found it. You’re human.

In your speech, you claimed not to understand how liberals could recognize the humanity of Palestinians when many of them have illiberal beliefs, when we hold views that “are completely incomprehensible on the streets of Gaza.” I think you should try harder to understand. Because it’s the same way we manage to recognize yours.

Immigrants serve in the U.S. military in about the same proportions as other demographics, but they’re uniquely unlikely to have older relatives who served in the U.S. military. Not that most native-born citizens could pass this test either, since Vance specifies that your loved one has to have died in a war. I’m not sure Vance can pass personally—his father survived Vietnam, and his cousin Nate is still alive, although they don’t seem to be speaking to each other. Nate Vance, a former Marine, volunteered to fight for Ukraine.

By which I mean that in 2001, New Yorkers paid more in federal taxes than the state received in federal funding, while Ohioans paid less than they received. Monsoon Wedding was a collaboration between a New York studio and an Indian one, so some of its $30 million box office gross would have gone into the pool paying for Vance’s public high school, and later to help pay for college. It’s another one of those “contradictions,” as Vance puts it, in the blue state mindset—we usually support policies that, on net, tax us more and send the money to red states. But, importantly, calculations like this are messy and approximate. You can’t neatly separate the peoples or economies of New York and Ohio.

Vance himself has Indian immigrant in-laws.

Aaron I really appreciate your explanation and analysis of the Vance comments and perspectives

I listened to the Ezra Klein interview with Yoram Hazony author of The Virture of Nationalism and I admit I was very confused. Would love a live discussion with you some time . Your thoughts here and letter to Vance are right on !