Who Shot Richard Honey?

Let's crack a two hundred years cold case.

Previously: In the 1820s and 30s, a popular movement led to dramatic reforms in Britain. Caroline of Brunswick played a prominent role, as did the incendiary political writer William Cobbett. Cobbett was also a farmer and helped spread techniques for growing root vegetables. Caroline was also the Queen of England.

Queen Caroline used everything in her life as ammunition against George IV, even her own death. When she suddenly got deadly sick in 1821, she announced that she was dying of a broken heart over her ill-treatment. The radical movement lost its figurehead and gained a martyr. They planned a massive demonstration at her funeral procession.

The government got wind of this and decided to reroute the queen’s body to avoid the city. Some of the protesters moved to block off the route and force the procession back towards the rest. A cavalry regiment, the 1st Life Guards, was dispatched to maintain order, but at a certain point, for disputed reasons, they started firing into the crowd. Two protestors were killed: George Francis, a bricklayer, and Richard Honey, a carpenter. Now the movement had three martyrs. Then they protested at Francis and Honey’s funeral, soldiers fired into that crowd, and so matters continued to escalate, culminating in what I’ve been increasingly thinking of as the Revolution of 1830.

My first plan for this article was to research what happened to the widows and orphans of the two slain men. Or at least Honey’s, because that’s a mildly unusual name and therefore might be easier to trace. But finding anything substantive about working-class people from this time period is really hard.

So instead, I turned to the other end of the pistol. Someone shot Richard Honey in the heart, which doesn’t feel like “crowd control gone wrong” so much as “murder.” Who was it? This research project went unreasonably well. I have it narrowed down to two suspects: the future husband of a famous novelist and a future notorious chief of police. (Really. I’m not concocting a conspiracy for fun like I did with Dickens, although Dickens does end up getting involved here too.)

Lieutenant Gore

Eyewitnesses, of which there were of course many, mostly agreed that it was an officer who fired the fatal shot. Even if they were wrong, it was definitely an officer who ordered shots to be fired, so the officer on the scene certainly gets a share of the guilt.

The 1st Life Guards, however, made it as hard as they could to figure out which officer that was. When witnesses tried to identify them, they showed up on horseback wearing masks, and, it was alleged, wigs and makeup. They gave contradictory stories and mostly claimed to have no idea who was there. Despite all this, public opinion soon singled out a prime suspect: Sub-lieutenant Charles Arthur Gore, of the Ormsby-Gores, universally referred to in print as “Lieutenant Gore.” Gore was memorable to witnesses because he didn’t really look like he belonged there—he came across like a frightened child who had accidentally been given command of a regiment. Everyone described him, and the shooter, with words like “young,” “small,” “effeminate,” and “handsome.”

One such witness was John Cam Hobhouse, a radical politician and close friend of Lord Byron, who knew Caroline personally and was in the funeral procession. In his diary, he wrote that he “had seen a small body of the Guards returning from the action headed by a young officer, who looked pale and frightened and ashamed, and that two or three men (one of whom had been cut in the hand) had told Hume and me that the officer was the man who had shot the man who had been killed.” He was not optimistic about Honey’s killer being punished, especially after learning who the coroner in the case was.

Saturday August 18th 1821: At Whitton. See by the Times that an inquest is sitting on the body of Honey, who was shot at Cumberland Gate. Higgs, the deputy coroner, seems a Kingsman, and doubtless some means will be adopted to frustrate the ends of justice. Francis, another man, dead. Walked out – dined – went in the water with my sisters. Cobbett very good on the Queen’s funeral.

Indeed, the inquest ended without naming anyone. The regiment as a whole was found guilty of murder—they hadn’t read the crowd the Riot Act, which would have made the killings legal. But you can’t put a regiment in prison.

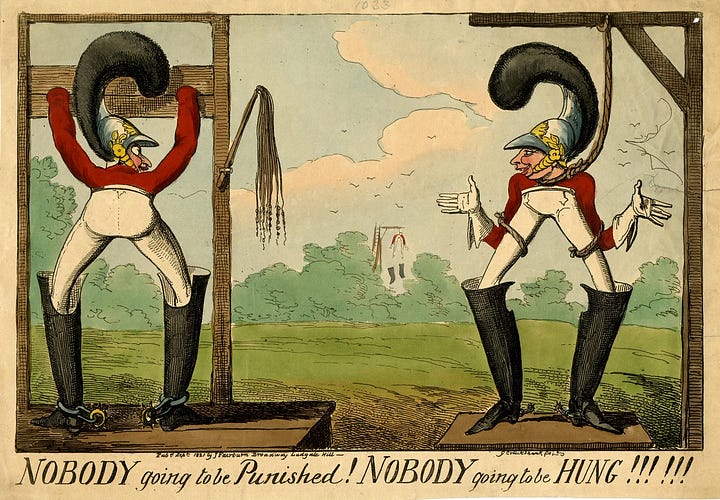

(from the British Museum, via this excellent article)

But most people were confident that Gore was the man. One political cartoon (left above) from George Cruikshank adapts a quote from Macbeth, with the word “gory” visibly crossed out and replaced with “bloody.” There weren’t any officers who could plausibly have been mistaken for him, and multiple witnesses ID’d him in the courtroom. He was caught sharing a smirk with the coroner and his barrister. Clearly Hobhouse was right to predict a brazen injustice.

But insiders, including Hobhouse himself, weren’t so sure about Gore. A later diary entry sees him learning from a government official, Richard Penn, that “it was well-known in the Life Guards who had shot Honey, but it was not Lieutenant Gore – Gore positively had no pistol on that day.”

Gore was a fairly common officer archetype. The third son of a minor peer, he had joined the army as soon as he could, to make something of himself, and bought a commission so that he could be an officer, as befits a gentleman. The 1st Life Guards might have looked, to him or his superiors, like a fairly safe posting with minimal responsibilities, perfect for a very young, effete man. Maybe he really didn’t have a pistol.

After this public shaming, he tried to continue his military career, buying a promotion to full Lieutenant the following year. But the year after that, he married a young poet named Catherine Grace Frances Moody, the witty daughter of a wine merchant. Both were marrying up, in different ways. Catherine married into very minor nobility, and Charles Gore married someone whose career was just getting started at the same time as his was stalling out. He sold his commission, intending for the two to live off of the proceeds while he looked for another job1. But Catherine, now Catherine Gore, quickly became the primary breadwinner of the household. To get out of the shadow of Lord Byron, she switched from poetry to prose fiction, which at the time was a more open field.

Her first novel, Theresa Marchmont, was a Gothic horror story: a virtuous woman marries an ex-soldier, unaware that he’s tormented by guilt over a dark secret. It opens with an epigraph from the same scene in Macbeth that the papers had used to obliquely accuse her husband:

“Take any shape but that, and my firm nerves

shall never tremble. Hence horrible shadow!

Unreal mockery, hence!”After Theresa, she wrote mainly in the Austen-esque “silver fork” genre—novels about aristocrats, purporting to be written by aristocrats for aristocrats, but actually written by and for the middle class. And she wrote a lot, which was her key to making a living. She published about 70 novels, plus short stories, plays, music, and a guide to rose gardening. When writing on unladylike topics, she used various pseudonyms, so there might be even more of her work we don’t know is hers.

Catherine’s lifelong marriage to Lieutenant Gore2 is a little evidence against him being the shooter. Catherine Gore was ideologically aligned with the protesters. One 1909 writer described her as “as democratic as Charlotte Smith, Mrs. Inchbald, Miss Mitford, or even William Godwin.” Queen Caroline shows up as a sympathetic character in some of her work. Her writing was often illustrated by George Cruikshank, the same artist who expressed outrage that the shooter was never punished. It’s weird enough that she had ten children with any of the soldiers from that day. Could it really have been the one who killed Honey?

But if not him, who?

Chief Constable Oakes

The last person to have tried to figure this out seems to be historian Wilhelmina Stirling, and her findings appear in her 1916 book A Painter of Dreams, and Other Biographical Studies. Stirling seems to have tracked down the man alluded to in Hobhouse’s diary as the real shooter. However, her sympathies did not lie with the protesters. She thought it only proper that his identity remained secret at the time, “to shield him from the animosity of an unreasoning mob,” and in her own work she censored the man’s name for the sake of his living descendants. She gave enough details, though, for me to dox him (sorry, descendants):

…later the true perpetrator of the much discussed deed was appointed to the first Chief Constableship which fell vacant. During his term of office he lived in close companionship with Lord Albemarle, and the latter used to relate that his friend was never the same man subsequent to the unfortunate episode which had marred his military career.

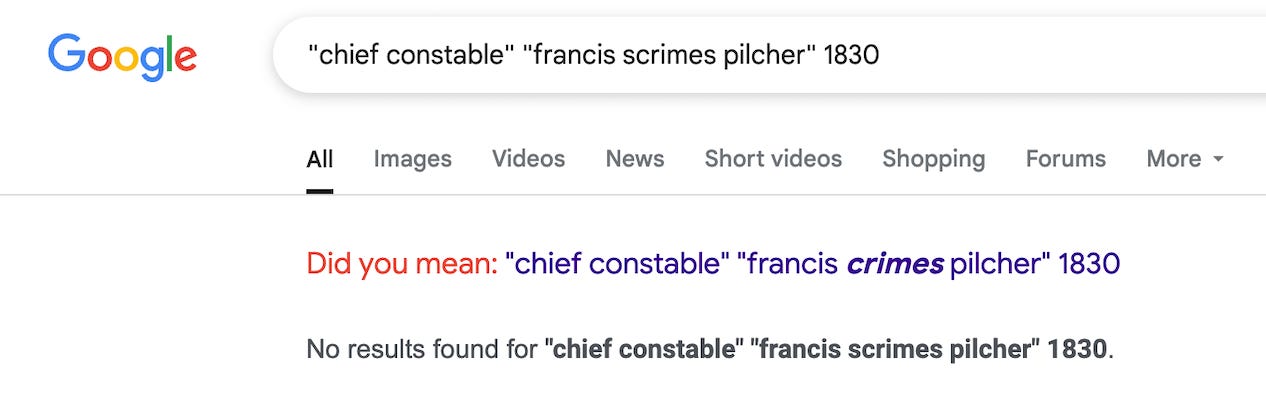

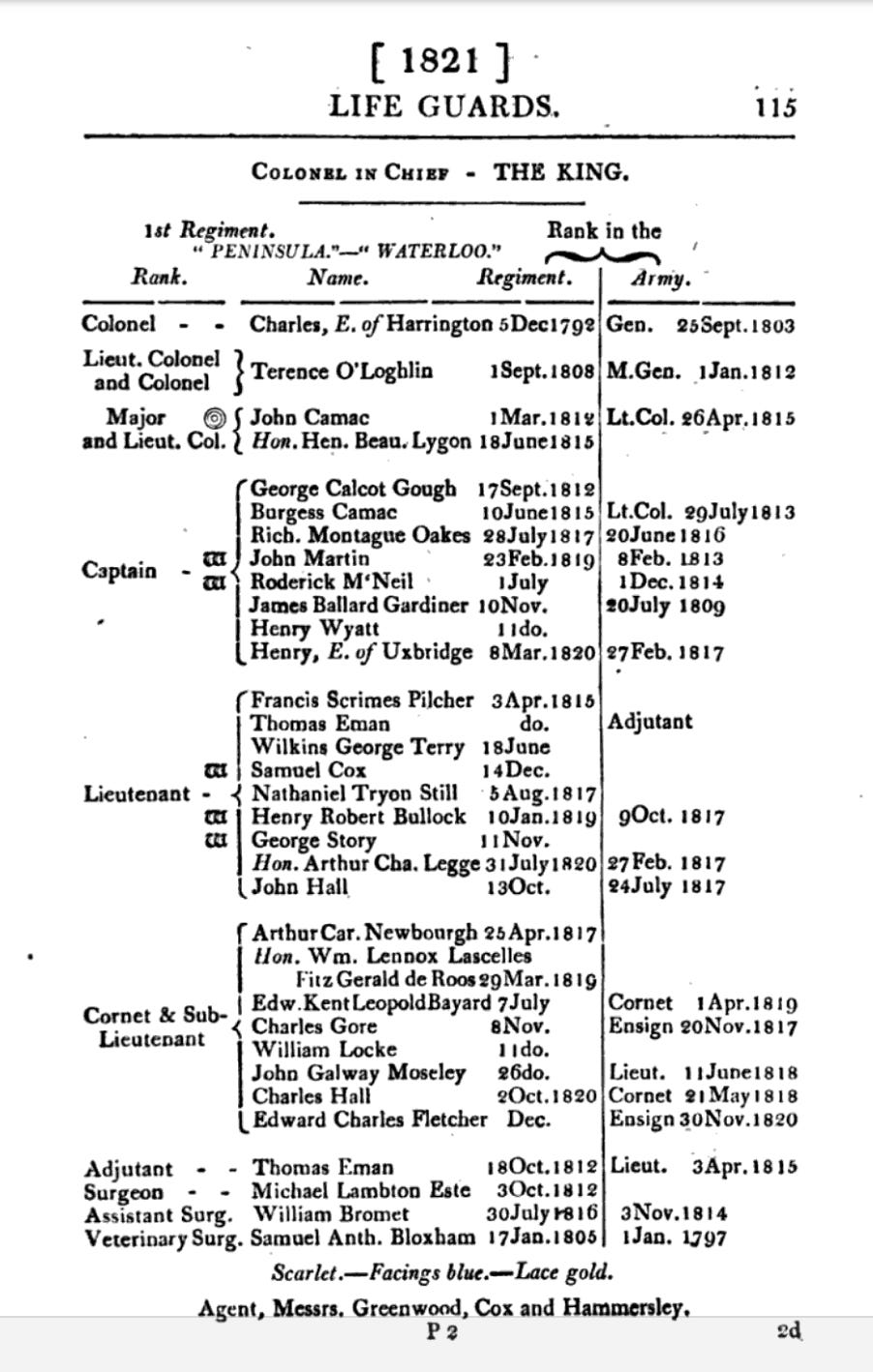

There’s only one Chief Constable who would have lived near Albemarle and his name appears in the roster of officers of the 1821 1st Life Guards. But, just to be sure, I briefly checked each of them3 in turn using an ultra-sophisticated research technique:

No, it has to be Captain Richard Montague Oakes, Chief Constable in Norwich, where Lord Albemarle lived. Oakes featured prominently in the trial, too, and I’ve since found a letter where Stirling names him.

Stirling notes a little irony in the friendship between Albemarle and Oakes—Oakes was part of Caroline’s story, and Albemarle was friends with Maria Fitzherbert, King George’s other wife. Apparently, he helped ensure Fitzherbert’s inconvenient marriage certificate survived in a bank vault. Since then, another piece of irony has cropped up: Albemarle is a direct ancestor of the current Queen Camilla.4

So, to recap, Oakes either illegally killed a man or helped protect the one who did, which hurt his military career, so to help him out Norwich made him chief of police. It looks like this worked out just about as poorly as you might expect. Oakes doesn’t come across well in the various documents in the public record. There’s an acrimonious exchange of letters with a citizen and an investigation into police brutality.

During his tenure, local lords even tried to get his entire police department abolished, saying that they hadn’t had any noticeable impact on serious crime, were over-prosecuting minor crimes, and cost a lot of money. The petition made it to the floor of Parliament, but there an MP read a letter from Oakes saying that actually his police were great, and that was that.

But the most damning indictment comes from his problematic investigation into another murder case: the 1848 murders of Isaac Jermy and his son at Stanfield Hall.

This one’s less of a mystery. It was almost certainly their tenant, farmer James Bloomfield Rush, who had stopped paying rent and started forging deeds to the estate. His plan was to kill the entire family and their servant, then blame it on the relatives who would otherwise inherit the property. But two of his four intended victims survived to identify him.

At the trial, the one sticking point was that the murder weapon had never been found. Oakes said that he and his men had painstakingly sifted through the entire property over several days, and while they found other evidence, no gun. It was an unprecedentedly thorough search, he said. But the eyewitness testimonies and circumstantial evidence were more than enough anyway. Rush was convicted, sentenced to death, and swiftly executed.

Then some laborers cleared away a pile of manure on Rush’s farm and found the murder weapon.

Oakes and his police, it seems, had not so much been “searching the property” as “providing free labor” to it. With Rush in prison, his son was in charge, and he only permitted the police to conduct searches that involved work he wanted to do anyway—clearing out ditches, consolidating piles of manure, turning over the soil, and so on. So the police dutifully looked in only the places the suspect’s son said to look, helping him out in the process. He’d said specifically not to look under the pile of manure in the yard, so rather than get a warrant, they just didn’t look there. But they still put out a statement claiming to have searched the entire farm thoroughly.

The fiasco was described in vicious detail in an article in the Examiner, one probably written by Charles Dickens, who had taken an early interest in the sensational case. The article comments:

In the administration of justice, as in most other things, nothing is more mischievous than false reliances. If the public had been informed that there was no search for the weapon with which the assassinations at Stanfield Hall were committed, as the son of the accused would not allow dung-heaps on the premises to be deranged, people would have known what to think about the matter; but the false supposition that a thorough search had been made without any result, might have weighed with persons in the jury-box, and improperly favoured the prisoners case, had the evidence in other respects been less decisive and conclusive.

Also, it appears, Oakes had agreed to withdraw from the property entirely by a certain deadline, in exchange for a promise from the Rushes that they wouldn’t take the opportunity to remove or destroy evidence. Which is bonkers. The article compares this to the superstition that you can catch a bird by putting salt on its tail.

When we see such an example as this, what a marvel it appears that the machinery of justice works under such numb-skull direction. No wonder that Rush reckoned so confidently on escaping justice, if he knew the discretion and ways of Norwich magistrates and constable.

Oakes somehow survived the ensuing vote of no confidence, but soon resigned anyway. He was presented with a silver vase in gratitude for his years of service.

Oakes or Gore?

First of all, I consider them both culpable. One of them did it, and the other one covered for him. I’m not a big fan of retributive justice, so I’m not too upset they went on to have decent second acts, but it is frustrating that the blood washed off their hands so quickly. Appointing Oakes as Chief Constable may have cost the Jermys their lives—if the constable’s inclined to help people get away with murder, it’s all the more tempting to commit your own.

I’m not even sure I believe Stirling that Oakes was traumatized and ashamed. There’s an account of him, as constable, teaming up with a cavalry regiment sent to quell a riot5 in the area. He didn’t have to be there in person, but he was.

In terms of the actual question of fact, I doubt I’m going to find conclusive evidence. Here’s my thinking, though. Oakes was tall and burly, so there’s little chance witnesses could have confused him and tiny little Charles Gore. Your height and build are quite a bit harder to disguise than your other physical features. Since multiple witnesses identified the shooter as Gore, certain conclusions come to mind.

In particular, it seems oddly convenient that the one officer who could be cleanly identified, the scrawny kid in the herd of big burly thugs, is also the one who done it. It’s completely plausible, but it’s a one in thirty chance. Conversely, suppose the protesters had no idea who did the shooting, in all the chaos. This wasn’t their first massacre. They knew, like Hobhouse, that the state and its enforcers would close ranks to protect their own. Their only chance at vengeance was if they could pin one or both of the killings on specific people, convincingly enough that their allies would cut them loose as a scapegoat. If they were to get their pound of flesh, they needed to all name the same culprit, and their only chance of that was to pick the one who looked different from all the others. So if they were lying or guessing, the odds are good they’d pick Gore.

This is fairly compelling evidence for Oakes. My money’s on him. But I’ll get back to you in a few decades, when I finish reading Catherine Gore’s work for clues.

Bonus: Non-radical swedes are as moldy as cheese

Chief Constable was actually the third act for Colonel Oakes. He first tried his hand at farming near the seaside in Norfolk, and failed rather spectacularly there too. His brother-in-law wrote a song parody about it, which includes this description of Oakes’s cultivation strategy:

Oh see ye turnips of emerald green

To the right and left, and the swedes between

Do ye ken the red mangels and quicksets clean

Where a man couldn’t thrust his palm in?

This implies that Oakes was not using the techniques William Cobbett had evangelized in the area. Cobbett wrote that Norfolk farmers referred to his suggested strategy for the planting of swedes (rutabagas) as “Radical Swedes,” and worried that

The “loyal,” indeed, may be afraid to adopt it, lest it should contain something of “radicalism.” Sap-headed fools!

So Oakes’s farm may have failed due to his politics. Rejecting the radical system, he planted his crops too close together, with the result that

The swedes are as moldy as Stilton itself

The mangels are rotting in shed and on shelf

Some sources describe him as unemployed, but there’s plenty of evidence that he eventually had a successful career as a public servant of some kind.

I seem to be the first, oddly, to make this connection. I have the full list of officers in the Life Guards in 1821, and there’s only one Gore, and all the dates and descriptions line up, so it’s definitely the same person.

The story of Camilla and Diana has strong echoes of the story of Fitzherbert and Caroline. In both, the Prince of Wales is quasi-secretly committed to a woman he’s been forbidden to marry, but reluctantly marries a more suitable woman. As the latter marriage disintegrates, the Princess of Wales turns to politics and the media in order to maintain her position, becoming the “people’s princess.” And then she dies young, and some people will always believe she was murdered by the crown.

The “riot” was a peaceful strike by dockworkers. They’d supposedly threatened to burn down the Mayor’s house, but they just marched past it after seeing it was heavily guarded.

This is such a great post. The research alone would carry it, but then your details and the humor. I laughed out loud a few times. I particularly loved the guy who got the police to do his work for him, but told them not to move (aka look under) THAT pile of shit. Very funny. I just started watching The Great, and I feel like this could be multiple episodes of a show like that!